Personal is Political: Are You Doing Your Work? White Transmen Holding Ourselves Accountable to Audre Lorde’s Legacy

By Andrew J. Young

When Aishah Shahidah Simmons first asked me to submit a piece to The Feminist Wire’s forum on Audre Lorde, I have to admit, I was nervous. Though I have considered myself a feminist for much of my relatively young life, it was only quite recently that I spent any meaningful amount of time reading and considering the work of Audre Lorde and other feminists of color. This past fall 2013 I had the privilege of taking Aishah’s graduate Introduction to Feminist Studies seminar at Temple University. Using a lens that was grounded in radical Black feminist and Indigenous feminist thought, the course examined how the intersections of race, gender, sexuality, and gender identity shaped how people are both categorized and socialized by these social constructions. And while my BA in Women’s and Gender Studies and graduate work in gender and queer studies has left me well-read on many topics, it is only in the past year or so that I have intentionally focused on reading the work of queers and feminists of color—a clear oversight on my part and perhaps a failure of academically situated, mostly white, feminist spaces. My recent awareness of the work of feminists of color, including Audre Lorde’s, developed alongside my decision to begin transitioning from female to male in the summer of 2012 and has deeply impacted my evolving identity as a white queer transman scholar/activist over the past year and a half. With that prologue, I’d like to begin with two observations.

Observation 1: I have come across a number of discussions—both scholarly and in activist communities—about the border wars between transmen and feminists (often specifically lesbian feminists, though not always lesbian separatist feminists). One point of contention centers on accusations of “gender treason” lobbed at transmen by lesbian feminists. Transmen’s act of transitioning is seen as a betrayal of their gender and feminist movements that have fought for women to be able to live outside of limited notions of femininity and heterosexuality—as masculine, as butch, as women-loving women. Transitioning is equated with abandoning the struggle for expanded gender roles and gender presentations. Accusations abound. Transmen are denounced for “taking the easy way out” and taking on male privilege instead of struggling (as a woman) in the feminist trenches fighting sexist oppression. Many transmen who identify strongly as feminists—myself included—and are deeply hurt by these accusations.

Observation 2: Many white (usually college-educated) transmen are particularly drawn to black feminism and women of color feminisms. Routinely, I hear transmen recite Audre Lorde quotes and reference Lorde, bell hooks, and Patricia Hill Collins. Since transitioning, I have also found myself more interested in women of color feminist writings than “mainstream” [read: white] feminist writings. While I don’t want to marginalize Black feminism as being only for Black women, there is something that makes me wary of white (trans)men spouting Audre Lorde soundbytes to one another, often with very few people of color present, particularly women of color.

I think point of resonance for white transmen with Black feminism is illustrated by Audre Lorde’s words in “Learning from the 60s.” She writes, “There is no such thing as a single issue struggle because we do not live single issue lives…Our struggles are particular, but we are not alone,” (Lorde [1984] 2007:137). Many, if not most, of the white transmen I hear drawing on Black feminism identify as queer, both politically and sexually. We understand the interlocking oppressions we face as both trans and queer. Our trans identities have also brought many of us into contact with diverse queer communities including people of color, low-income people, and people without health insurance who we very well may not have ever interacted with were we not trans-identified. Our trans identities also place us in an uncomfortable and tenuous relation to the State. A relationship similar, but not the same, as people of color—which we would likely never have experienced were we cisgendered. Many white transmen who struggle against oppression on multiple fronts want to be in solidarity movements with women-identified feminists. Black feminism, which often speaks for the need to act in solidarity with Black men though not without a critique of Black men’s sexism, seems a much more hospitable and intersectional than many of the white feminist spaces we have come from.

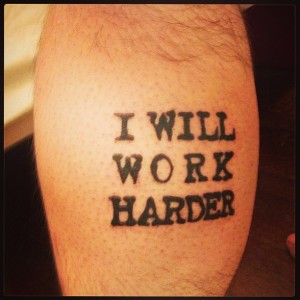

This tattoo on my left calf was inspired by many voices, but one of the most insistent was Lorde’s asking me, “Am I doing my work?”

We want to be accepted as feminists and allies based on our politics and not essentialist presumptions about our gender or bodies. Transmen, like all people, are a combination of our identities both privileged and oppressed. Our gender does not define us any more or less than it defines women-identified feminists. Black feminism, particularly Audre Lorde’s work, opens up a space for understanding ourselves intersectionally and working across difference, which is why many transmen are drawn to it.

And yet, what we, as white transmen, must be absolutely vigilant against is the presumption that—because of our experiences on “both sides” of sexist oppression—we are better equipped to lead the feminist movement. And as transmen uniquely situated to critique essentialist, determinist narratives of power and privilege, we must embody an intersectional politic, struggling against sexism alongside racism, classism, heterosexism, and able-ism. Here, Audre Lorde’s words may be most powerful for us.

In her essay “Sexism: An American Disease in Blackface” Lorde challenges Black men’s justifications of sexism and the oppression of Black women, highlighting how racism and sexism are intertwined. Ideals of masculinity function to both justify violence against women and sanction racist violence in a society that sees Whiteness as properly masculine and Blackness as deviant. Lorde tells us that “one oppression does not justify another,” ([1984] 2007:63) and that separatist solutions to racism, sexism, heterosexism are destined to fail.

I fear that white transmen, queer or otherwise, are quick to take up Lorde’s call to embrace difference, as well as her focus on intersectionality and the value of each individual’s experiences, while forgetting white and male privilege. Our tendency is to read Lorde and other feminists of color and say, “Look at me! I’m oppressed too, even though I’m white!” Or to feel as though our oppressed trans-identities have somehow absolved us of needing to check ourselves on racist, sexist, or ableist comments and actions. Many trans-folks wear their trans-ness like a medal, a gold—or at least a silver—in the Oppression Olympics. As transmen, we cannot forget to take up Lorde’s critique of race and gender privilege along with her call to work across difference.

One oppression does not necessarily equal or erase another. My anger that my top surgery was not covered by my health insurance does not justify a lack of support for struggles against forced sterilization by Native American women; it calls for participation in a wider movement to provide safe and consensual healthcare for all people, not just a push for trans-care to be included in my private, employer-provided healthcare plan.

I hope white trans-folks, especially transmen, will continue to turn to Audre Lorde and other feminists of color for inspiration and guidance in our growth as social justice advocates. Lorde’s legacy, her continued questioning in “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action,” “Are you doing your work?” (Lorde [1984] 2007) pushes me to continually reassess my thoughts and actions. What is my work? Am I doing it in a way that is inclusive? Am I fighting for a single-issue solution or am I struggling against oppression and domination more broadly? The challenge is to answer these questions critically and honestly. White trans men can play a powerful role in educating ourselves and others about interlocking oppressions and privileges, but our trans-identity can easily become a crutch to prop up hollow recitations of pithy quotes with activist cachet. It doesn’t matter how many times you can work “the master’s tools” into a conversation. It matters that you are doing the work to undermine and transform structures of oppression that hold us all hostage in this “dragon we call america” and around the world. But that, perhaps, is the most important part of Lorde’s legacy: her insistence that we do better. Together. Every day.

Works Cited

Lorde, Audre. [1984] 2007. Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. New York: Crossing Press.

_______________________________________________________________

Andrew is currently a third year PhD student in sociology at Temple University with a focus on gender and sexuality, specifically on queer and/or trans* identities and the sexualization of culture. He is planning on writing his dissertation on queer and feminist pornography as tool for social justice work. Originally from Illinois, he holds bachelor’s degrees in Philosophy and Women’s and Gender Studies, as well as a master’s degree in Philosophy and Social Policy, from American University in Washington, DC. Andrew has spoken on his experience as a white, queer, able-bodied transman and intersectionality in many venues including multiple colleges and universities, the Civic Education Project at Northwestern University, and The Philadelphia Trans-Health Conference.

Andrew is currently a third year PhD student in sociology at Temple University with a focus on gender and sexuality, specifically on queer and/or trans* identities and the sexualization of culture. He is planning on writing his dissertation on queer and feminist pornography as tool for social justice work. Originally from Illinois, he holds bachelor’s degrees in Philosophy and Women’s and Gender Studies, as well as a master’s degree in Philosophy and Social Policy, from American University in Washington, DC. Andrew has spoken on his experience as a white, queer, able-bodied transman and intersectionality in many venues including multiple colleges and universities, the Civic Education Project at Northwestern University, and The Philadelphia Trans-Health Conference.

Pingback: Weekly Feminist Reader

Pingback: Afterword: Standing at the Lordean Shoreline - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire