Schooling the Generations: Education and the Relevance of Mumia Abu-Jamal in Times of Crisis

By Christopher M. Tinson

Creating a classroom environment that fosters radical education first requires courage to confront uncomfortable truths about American society. Introducing students to Mumia Abu-Jamal‘s radical pedagogy at one of this country’s predominantly white, liberal arts, private colleges, however, also requires negotiating. Most of my students come from communities that have not been subject to heavy police presence. Many have not studied the history of racial oppression in the United States. Beyond Dr. “I Have a Dream,” the tired seamstress, and Spike Lee’s Malcolm, they know very little about African American freedom struggles. Moreover, upon entering, they have not had an African American professor teach such history or any history for that matter. In this context, both courage and negotiation are critical assets to ones instructional practice.

Creating a classroom environment that fosters radical education first requires courage to confront uncomfortable truths about American society. Introducing students to Mumia Abu-Jamal‘s radical pedagogy at one of this country’s predominantly white, liberal arts, private colleges, however, also requires negotiating. Most of my students come from communities that have not been subject to heavy police presence. Many have not studied the history of racial oppression in the United States. Beyond Dr. “I Have a Dream,” the tired seamstress, and Spike Lee’s Malcolm, they know very little about African American freedom struggles. Moreover, upon entering, they have not had an African American professor teach such history or any history for that matter. In this context, both courage and negotiation are critical assets to ones instructional practice.

I had the fortune of being introduced to Mumia’s case in the 1990s by a close friend, at a time when global demands to stay his execution were at a fever pitch. Over the years, Mumia’s case and condition have continued to influence my understanding of the police, courts and imprisonment. Since 2009, I have taught a course that is inspired by the struggle of political prisoners, especially those with active participation in Black liberation politics.[i] Mumia’s commentaries at Prison Radio are fixtures on my syllabi; often I play them at the start of course meetings. The course ranges from histories of some of America’s oldest and most notorious prisons, to the War on Drugs, to antiblack criminalization, to women and mothers’ imprisonment, including the unique patterns of gendered violence that mark incarcerated queer and trans bodies. Although “mass incarceration” and Jim Crow 3.0 have attracted wider attention than at any point since the initiation of the War on Drugs, upon enrolling in the course students are hard pressed to know anything about Mumia Abu-Jamal. Considering the “dead zones of the imagination” that many of our middle and high schools have become, perhaps this fact comes as no surprise. Moreover, the struggles of political prisoners are beyond the pale of understanding in a general educational climate that is at best indifferent to Black political desires.

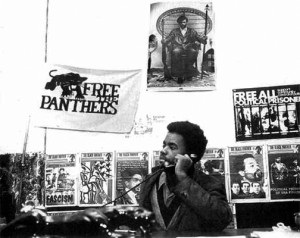

One of the pivotal texts that seized my interest in Mumia’s life in the 1990s was Chinosole’s edited collection, Schooling the Generations in the Politics of the Prison. Though out of print, it is significant for historicizing carceral wars of repression as a constituent element of African diasporic experience, while also demonstrating critical histories of resistance as liberatory epistemology. Cautioning against the effects of COINTELPRO, she writes: “The freedom sought through these pages, then, is not only from the effect of U.S. policies of containment, but also from the direct result of low intensity intelligence warfare which spawns self-inflicted containment practices of non-communication, distrust, and fear inside Afrikan/Black organizations.” Mumia’s enlistment in the Black Panther Party as a youth, a membership he says he was beaten into by police, was chiefly an education in state-sponsored urban warfare, tactics that relied on organizational infiltration, elaborate lessons in sabotage, and exhilarating lectures on the incarceration or assassination of leaders and rank and file members with impunity. A school of hard knocks, if there ever was one.

There is perhaps no more fitting an example than Mumia to elucidate the stakes of political struggle in the U.S. Through him students are introduced to histories of COINTELPRO, police antagonism and corruption in Philadelphia, urban rebellion and organizational histories of the Black Panther Party, the Black Liberation Army, and the MOVE organization as key cultural and political shifts in U.S. history. With writings and commentaries by Mumia as guides, students come to observe the transition from the welfare state to the punitive state. Moreover, students are encouraged to observe and interrogate the convergence between the War on Drugs and the War on Terror as recalibrations of earlier disciplinary paradigms. Ultimately, this course familiarizes a new generation of students with these histories in the hope they will commit to a deeper understanding of Mumia’s case and the long, tenuous history of political struggle he represents.[ii]

There is perhaps no more fitting an example than Mumia to elucidate the stakes of political struggle in the U.S. Through him students are introduced to histories of COINTELPRO, police antagonism and corruption in Philadelphia, urban rebellion and organizational histories of the Black Panther Party, the Black Liberation Army, and the MOVE organization as key cultural and political shifts in U.S. history. With writings and commentaries by Mumia as guides, students come to observe the transition from the welfare state to the punitive state. Moreover, students are encouraged to observe and interrogate the convergence between the War on Drugs and the War on Terror as recalibrations of earlier disciplinary paradigms. Ultimately, this course familiarizes a new generation of students with these histories in the hope they will commit to a deeper understanding of Mumia’s case and the long, tenuous history of political struggle he represents.[ii]

In an era when collective efforts at social redress are mocked, Mumia’s work dramatizes the urgency of radical solidarity. In spite of his captivity he has remained a punctual and precise commentator on myriad issues including the Arab Spring, Occupy, the state executions of Troy Davis and Stanley Tookie Williams, and the sprawling Homeland Security apparatus. Moreover, Mumia has challenged the phallocentric historical record by emphasizing the work and vision of black women leadership in the Black Panther Party. His demonstrable command of the literary, cultural, spiritual, and political struggles that give meaning and substance to the global experience of African descendants situate Mumia’s thought firmly and unapologetically within the Black radical tradition. At each turn, the tenor of his political vision harmonizes an ethical opposition to racism, militarism, and exploitation into an active rebuking of carceral state logic and uncritical U.S. nationalism.

I am reminded of Assata Shakur’s letter from the world of exile in support of Mumia, where she instructs us “not to forget, and not to betray our living heroes. If we ignore their struggle, we are ignoring our own. If we betray our living history, then we are betraying ourselves.” As a living testament to ongoing movements for justice, Mumia and numerous other political prisoners disrobe the tradition of vindictive carceral thinking that is uniquely American. We need look no further than the application of the death sentence based on faulty evidence, the wanton use of solitary confinement, and the repeated attempts to silence him as examples of an evolving carceral practice aimed at masking social crisis.

I am reminded of Assata Shakur’s letter from the world of exile in support of Mumia, where she instructs us “not to forget, and not to betray our living heroes. If we ignore their struggle, we are ignoring our own. If we betray our living history, then we are betraying ourselves.” As a living testament to ongoing movements for justice, Mumia and numerous other political prisoners disrobe the tradition of vindictive carceral thinking that is uniquely American. We need look no further than the application of the death sentence based on faulty evidence, the wanton use of solitary confinement, and the repeated attempts to silence him as examples of an evolving carceral practice aimed at masking social crisis.

A regenerative movement for Mumia Abu-Jamal’s release provides educators the fortune of centering his revolutionary and revelatory contributions in their teaching of U.S.-based political activism. As my students have shown, there are countless lessons to be drawn from his case, including the expansive uses of punitive technologies; prison writings as antiracist knowledge production; the role and risks of jailhouse lawyers, and the cementing of antiblack racism as illustrative of our current “penal democracy.” Undoing Mumia Abu-Jamal’s long-term captivity will not only require courage and skills at negotiation demanded in the classroom, but also tenacity in facing the challenge of building the movement he will join upon his release from the death camp. As students of the vision and principles of one of the premier master-teachers of our day, we can do nothing less.

*The author would like to thank Connie Wun, Allia Matta, and forum editor Tanisha Ford, for their feedback on earlier drafts of this article.

****

Get involved with the Free Mumia Campaign

Bring Mumia Home Website

Bring Mumia Home on Twitter

“60 for Mumia’s 60th Birthday” IndieGoGo Campaign

Free Mumia Petition (Change.org)

_________________________________________________________

Christopher M. Tinson, Ph.D. is an assistant professor of Africana Studies at Hampshire College. His writings have been published in The Black Scholar, The Journal of African American History, The Nation, and he recently coedited a special issue of the open-source journal, Radical Teacher on Hip Hop and Critical Pedagogy. He is currently working on a book on Liberator Magazine and Black Political Ruptures of the 1960s. And since 2006, he has cohosted the Hip Hop-rooted social justice program TRGGR Radio on WMUA, broadcasting from Amherst, Massachusetts to the world.

Christopher M. Tinson, Ph.D. is an assistant professor of Africana Studies at Hampshire College. His writings have been published in The Black Scholar, The Journal of African American History, The Nation, and he recently coedited a special issue of the open-source journal, Radical Teacher on Hip Hop and Critical Pedagogy. He is currently working on a book on Liberator Magazine and Black Political Ruptures of the 1960s. And since 2006, he has cohosted the Hip Hop-rooted social justice program TRGGR Radio on WMUA, broadcasting from Amherst, Massachusetts to the world.

[i] The title of my course is borrowed from a collection of critical writings about the U.S. carceral landscape edited by Joy James, Warfare in the American Homeland: Policing and Prison in a Penal Democracy (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2007).

[ii] Some of my former students, including Lyla Bugara, have already begun carrying on the work she started in my course Warfare in the American Homeland. She has interned with Human Rights Watch, the Correctional Association of New York, and is currently on staff at ColorofChange. Other former students, such as Courtney Hooks, Gillian Cannon, Aurelis Troncoso, and Jeff Deutch have worked with organizations such as the Prison Birth Project, Books Not Bars, Justice Now, Friends of Island Academy, Rosenberg Fund for Children, Real Cost of Prisons Project, Decolonize Media Collective, and Students Against Mass Incarceration among numerous others.

Pingback: Afterword: A Love Letter to Mumia - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire