COLLEGE FEMINISMS: The Synonymy of Disease and Sick: A Critique of the American Diabetes Association

By Savannah Johnson

If I could bottle magic, I would store it in a vile of insulin. You might imagine me awake in my kitchen late at night, brewing an injectable diabetes-reversing agent. I’d draw it up in one of my syringes, and bam! No more dis in my ease. Oh, the bear hugs I’d receive. People would say to me, “You’ve earned a normal life! Enjoy living it!” They’d say, “If anyone deserves to be happy, it’s you, Savannah!” There’d be a party for sure now that I can—gasp!—eat candy. But I keep wondering why can’t I be happy with diabetes. What is it about a happy diseased person that confuses people? Am I abnormal because of my diabetes? Hey, I actually can eat candy!

If I could bottle magic, I would store it in a vile of insulin. You might imagine me awake in my kitchen late at night, brewing an injectable diabetes-reversing agent. I’d draw it up in one of my syringes, and bam! No more dis in my ease. Oh, the bear hugs I’d receive. People would say to me, “You’ve earned a normal life! Enjoy living it!” They’d say, “If anyone deserves to be happy, it’s you, Savannah!” There’d be a party for sure now that I can—gasp!—eat candy. But I keep wondering why can’t I be happy with diabetes. What is it about a happy diseased person that confuses people? Am I abnormal because of my diabetes? Hey, I actually can eat candy!

In The Difference that Disability Makes, Rod Michalko argues that “contemporary culture, particularly Western culture, represents disability as something that should be prevented or cured and sees disability as a tragedy that befalls some people.” Upon learning about my diabetes, people typically have one of two reactions: “Oh, I’m so sorry!” or “My grandma has that!” Sometimes they ask, “Does it hurt to prick?” But then, they usually apologize. “Oh, wait, I shouldn’t ask questions. Sorry.” These endless regrets practically nip my islet-cell-lacking pancreas. I usually chalk these exchanges up to the negative connotations the word disease carries as a result of the social code: pity “the sick.” Unfortunately, the synonymy of disease and sick is often perpetuated by the American Diabetes Association (ADA), which remains one of the largest diabetes advocacy organizations in the nation.

The ADA conducts two annual awareness campaigns that focus primarily on the negative aspects of diabetes: American Diabetes Month in November and American Diabetes Alert Day on the fourth Tuesday of every March. The former is “a time to bring even greater awareness and attention to the seriousness of diabetes, and its deadly complications,” and the latter is “an annual one-day wake-up call to inform the American public about the seriousness of diabetes.” One of the ADA’s primary goals is to “prevent and cure diabetes and to improve the lives of all people affected by diabetes” between 2012 and 2015. At first glance, one might be inclined to admire this lofty goal. On the other hand, I wonder why it is assumed that the lives of diabetics need improving. Along these lines, it’s important to point out that no part of the ADA’s Strategic Plan includes proposals intended to help diabetics with self-acceptance or confidence. Rather, their efforts to prevent diabetes, as well as to reduce amputations, hyperglycemia, and discrimination are emphasized. In order to illustrate the ways in which this approach perpetuates the marginalization of “disabled” bodies, I will examine an “I Decide” video produced by the ADA, as well a poster. Additionally, I will also showcase two campaigns that I created—print and audiovisual—that challenge this approach and offer new ways of thinking about diabetes.

The ADA conducts two annual awareness campaigns that focus primarily on the negative aspects of diabetes: American Diabetes Month in November and American Diabetes Alert Day on the fourth Tuesday of every March. The former is “a time to bring even greater awareness and attention to the seriousness of diabetes, and its deadly complications,” and the latter is “an annual one-day wake-up call to inform the American public about the seriousness of diabetes.” One of the ADA’s primary goals is to “prevent and cure diabetes and to improve the lives of all people affected by diabetes” between 2012 and 2015. At first glance, one might be inclined to admire this lofty goal. On the other hand, I wonder why it is assumed that the lives of diabetics need improving. Along these lines, it’s important to point out that no part of the ADA’s Strategic Plan includes proposals intended to help diabetics with self-acceptance or confidence. Rather, their efforts to prevent diabetes, as well as to reduce amputations, hyperglycemia, and discrimination are emphasized. In order to illustrate the ways in which this approach perpetuates the marginalization of “disabled” bodies, I will examine an “I Decide” video produced by the ADA, as well a poster. Additionally, I will also showcase two campaigns that I created—print and audiovisual—that challenge this approach and offer new ways of thinking about diabetes.

If I were to hear just the audio accompanying this “I Decide” video, I would assume they were spotlighting a natural disaster or international poverty. However, the ADA employs depressing music in order to highlight the usually rare but serious effects of diabetes. The music complements the somber and distressed tone of the mother whose daughter was recently diagnosed with diabetes. The girl’s baby pictures are showcased throughout the video, as the mother proclaims their desire to “fight diabetes.” The assumption here is that one must expend inordinate amounts of time and energy eliminating the burden of having diabetes.

Additionally, the idea of “fighting diabetes” seems counterproductive. First, there is no cure for diabetes, so it doesn’t seem useful to fight something that quite literally cannot be fought. Second, it seems that “fighting diabetes” shifts focus away from more productive efforts, such as raising awareness and supporting diabetics. The mother also highlights “blindness” and “kidney disease” in a tone that encourages the viewer to buy into sick roles, the socially accepted ways to treat “the sick.” On the other hand, she claims not to want her daughter to deal with the possible health complications that diabetes may cause. This is contradictory, because the former approach encourages viewers to regard diabetics as walking health complications. In Exploring Disability, Colin Barnes and Geof Mercer identify “disability” as a label assigned by the able-bodied to people that may not even consider themselves disabled. This is especially important to consider in this case, because the daughter—the actual diabetic—is rendered practically silent in the video, particularly regarding her experiences with diabetes.

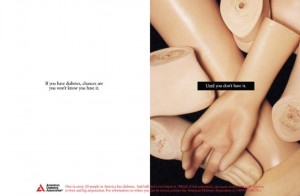

The ADA poster (right) is problematic for similar reasons, as it focuses on the notion that diabetics have greater chances of losing limbs or extremities. Based on theories developed by David M. Boush, Marian Friestad, and Gregory M. Rose, I would argue that these scare tactics perpetuate fear of disease for everybody, not just the diseased. These types of campaigns also normalize the pitying of disabled bodies, as well as our marginalization. While there are definitely times when I think life would be easier without diabetes, we must not pity what is abnormal to us. Rather, it is my contention that normalcy is relative to individual circumstance.

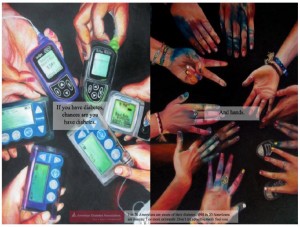

In my video (below), upbeat lighthearted music plays throughout in order to highlight my own outlook on diabetes. To me, a necklace is a necklace, just as diabetes is just diabetes—something that is dealt with every day, but that is a normal component of life. When I was thinking about ways to challenge the print campaign, I immediately thought about paintings my friend Lauren Pizzi did of two photographs I took at diabetes camp. In the first (left), our hands visibly hold our insulin pumps in a unity circle. In the second (also left), our hands are also in a unity circle, covered in tie-dyed friendship bracelets, rings, and medic alerts—all things colorful, happy, and campy. I wanted my poster to be satirical—obviously if a person is holding an insulin pump, they have both diabetes and hands. The stark clarity of my wording serves to remind people that diabetes is to diabetics as hands are to everyone, normal. In this way, I hope that my viewers reconsider the fear culture around diabetes.

In my video (below), upbeat lighthearted music plays throughout in order to highlight my own outlook on diabetes. To me, a necklace is a necklace, just as diabetes is just diabetes—something that is dealt with every day, but that is a normal component of life. When I was thinking about ways to challenge the print campaign, I immediately thought about paintings my friend Lauren Pizzi did of two photographs I took at diabetes camp. In the first (left), our hands visibly hold our insulin pumps in a unity circle. In the second (also left), our hands are also in a unity circle, covered in tie-dyed friendship bracelets, rings, and medic alerts—all things colorful, happy, and campy. I wanted my poster to be satirical—obviously if a person is holding an insulin pump, they have both diabetes and hands. The stark clarity of my wording serves to remind people that diabetes is to diabetics as hands are to everyone, normal. In this way, I hope that my viewers reconsider the fear culture around diabetes.

Both of my campaigns were developed after studying Kathleen LeBesco’s analysis of HBO’s The Sopranos’ treatment of non-normative bodies. LeBesco argues that the show highlights a plethora of bodies that are “feared or reviled to different degrees in everyday life,” but notes how “they’re mostly just another fact of life” and are made to be “comprehensible to the audience.” She claims that when diseases or disabilities are presented as normal for the characters living with them, the audience understands the sense of normalcy and is less likely to feel pity. When a character is entirely their disease, there is an unspoken norm for how to talk to and treat them, whereas when a character is a complete and complex person with a disease, the discourse is less objectifying.

I am a person, not a disease. Diabetes does not define me entirely, but it certainly helps explain part of me. I wanted to normalize my diabetes and diabetes in general, which is just another characteristic of me—like my blue eyes and pierced ears. I want viewers to know that I do not warrant pity or apologies and that my life is fulfilling.

_______________________________________________________

Savannah is a junior at Colorado College majoring in Sociology and double-minoring in Feminist and Gender Studies and Education. She is the Founder of OrgasmiCC, a sex-positive feminist student organization dedicated to improving sexual autonomy and communication, and the Co-President of Colorado College’s Feminist Collective (FemCo). Her favorite word is “haecceity” (hek-see’i-tee, n. laying, from haec, this), the aspect of existence on which individuality depends; the hereness and nowness of reality. First coined by the philosopher Duns Scotus, haecceity is that indescribably sense one gets of being in the present tense, the pure experience of a single moment in time without defining the moment on the past or the future. For Savannah, haecceity would not be attainable without bell hooks and the women like her; therefore, she has it tattooed on her fourth finger for the four letters in hooks’ first name.

0 comments