On Disability and Cartographies of Difference

By Wilfredo Gomez

I recently returned to my alma mater to encounter a rather peculiar and interesting narrative about my legacy. While interacting with former teachers, classmates, and current students, stories were told about the years I spent at the school. One person told a story about  how I played varsity basketball during my last year of high school, never having played a single minute. I trained in silence, dedicating time and effort for three years, being overlooked until I finally got my break. I rode the bench and never paid attention to the games, as I was too focused on academics and trying to get somewhere. But in the last game of the season with 15 seconds left on the clock, the captain of the team called a time out and requested I join the team on the court. With the clock winding down to zero, I was told to stand in the corner and wait for a pass. That pass was delivered as promised and the defense collapsed on me, forcing me to hesitate and give the ball up. The ball came back my way where I dribbled to my left and took a shot over the outstretched arms of two defenders who may as well have been giants. While a blur, the shot went in as time expired, the only two points I scored in my career, and fans rushed the court emptying the stands, lifting me up in celebration of my presence and shot. I was the team’s good luck charm. Another person told a story about how I was confined to a wheel chair and they had fond memories of my racing up and down the hallways as I moved from class to class. They recalled my playing basketball, not playing, and leaning over to my fellow teammates saying that I was headed somewhere. One would think that if these narratives were to have gotten out to the public, they might have attracted the attention of ESPN. These recollections of heroic feats and athletic persistence were only partial to the narratives of the legacy I have left behind.

how I played varsity basketball during my last year of high school, never having played a single minute. I trained in silence, dedicating time and effort for three years, being overlooked until I finally got my break. I rode the bench and never paid attention to the games, as I was too focused on academics and trying to get somewhere. But in the last game of the season with 15 seconds left on the clock, the captain of the team called a time out and requested I join the team on the court. With the clock winding down to zero, I was told to stand in the corner and wait for a pass. That pass was delivered as promised and the defense collapsed on me, forcing me to hesitate and give the ball up. The ball came back my way where I dribbled to my left and took a shot over the outstretched arms of two defenders who may as well have been giants. While a blur, the shot went in as time expired, the only two points I scored in my career, and fans rushed the court emptying the stands, lifting me up in celebration of my presence and shot. I was the team’s good luck charm. Another person told a story about how I was confined to a wheel chair and they had fond memories of my racing up and down the hallways as I moved from class to class. They recalled my playing basketball, not playing, and leaning over to my fellow teammates saying that I was headed somewhere. One would think that if these narratives were to have gotten out to the public, they might have attracted the attention of ESPN. These recollections of heroic feats and athletic persistence were only partial to the narratives of the legacy I have left behind.

I ask this question in part as a disabled Latino who has and is still coming to terms with being disabled. How has time and context impacted my understanding of having cerebral palsy? How has cerebral palsy complicated the finite ways in which language appears and/or disappears in the face of the passage of time? These are but some of things I find intriguing as peers and family surround me, and I am reconnecting with the community and communities that constitute home.

Memory is a fraught thing, an abstract pastiche of experience, the processing of those experiences, the sensations they illicit, and the perceptions that are more frame of reference, and less lens from which to view the world. As such, memory is a slippery synthesis where effect and affect collide to inform and construct the narratives that we tell through space and time. While there are tangible narratives that inform the individual and their relationship to the collective experience of remembering, it is the intangibles rooted in and through the lens of being and presence that inform and are informed by the language(s) we have at our disposal. To this effect, I ask, what are the narratives that circulate around the experiences of being disabled, as opposed to being exposed to the disabled? In what ways does the nature of these experiences and exposure change through time? What is the lexicon that we rely on to tell narratives of the disabled vis-à-vis the experiences of the able-bodied? Furthermore, what languages and frames of reference are lost in the process? How do we identify them and are they worth excavating from the depths of our collective memories?

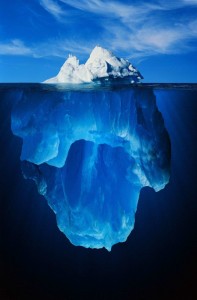

The experience of being disabled is perhaps one most appropriately captured by the use of a metaphor: that of the iceberg submerged in a body of water. That said, there is that which is visible and that which is invisible. However, whether our disabilities are visible or invisible, there are always specters of disability looming, the conscious and unconscious choices that situate how we understand our encounters with the disabled, the extent of those encounters, as well as the expectations that accompany them. Central to this discussion is the question of performance: what does it mean to perform disability? What is an accurate representation of said performance and is it ever consistent with the nuances of reality?

a body of water. That said, there is that which is visible and that which is invisible. However, whether our disabilities are visible or invisible, there are always specters of disability looming, the conscious and unconscious choices that situate how we understand our encounters with the disabled, the extent of those encounters, as well as the expectations that accompany them. Central to this discussion is the question of performance: what does it mean to perform disability? What is an accurate representation of said performance and is it ever consistent with the nuances of reality?

With time, access, and increased education, words like “disability” and increasingly disability studies and disability policy have come into consciousness. They have taken on new significance and have effectively changed the landscape of how I understand my intersecting identities as urban, disabled, and Latino. And while disability and disability studies is a pertinent lens that frames discourses and experience, gone is the language of being handicapped. Thus begins the occupation of a newly created liminal space that seeks to cultivate both public and private spheres amidst the able-bodied world(s) I have inherited. To be educated, Latino, urban, articulate, and a person with cerebral palsy is the equivalent of being able-bodied and disabled simultaneously. It is about being alternately-abled and subscribing to a different-ability set, in spite of the ways in which institutions construct, command, and control our respective bodies.

Language plays a prominent role in the ordinary being transformed into the extraordinary, as memory-making and recalling memory afford us a space to claim a progressive view towards the disabled in an ableist society. Memory and language construct narratives about reality wherein none existed or had credibility before. In remembering, disability appears to be an identity that is an approximation of being able-bodied, a surreal recollection of experience that comes to trump experience itself. To this effect, I have to force myself to remember in what ways words like “disability” and “handicap” were once used interchangeably. How were these words deployed and in what ways were they being understood and being given meaning? Might the language of handicap afford us a discursive lens through which to assess and evaluate being differently or alternately abled? What are the consequences in making such decisions? How do we account for the disabled who are indeed able-bodied in some contexts and disabled in others?What are the points of convergence and divergence whereby the individual(s) and institution(s) overlap? In what ways has our understanding of language limited the prospects of how the disabled relate to institutions?

It is this very question of language, institution, and memory that offers a blueprint for a cartography of difference, especially as it relates to institutional change, disability policy, and the future study of disability as these identities find open social, cultural, and political expression in being contested, constructed, contradicted, and performed.

____________________________________________

Wilfredo Gomez is an independent scholar and researcher. His research interests focus on education and popular culture throughout the African diaspora, with an emphasis on music, film, language and disability studies. He can be reached via email at gomez.wilfredo@gmail.comor via Twitter at BazookaGomez84.

Wilfredo Gomez is an independent scholar and researcher. His research interests focus on education and popular culture throughout the African diaspora, with an emphasis on music, film, language and disability studies. He can be reached via email at gomez.wilfredo@gmail.comor via Twitter at BazookaGomez84.

Pingback: Afterword: The Disability Forum - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire

Pingback: Weekend Links Vol. 20: Working on the Fall Issue | Bluestockings Magazine