A Trip to Richmond

By Starita Smith

Richmond, Virginia is the ultimate recycling of the human experience. It is like an urban trompe l’oeil in which places where atrocities had been committed upon enslaved people have been transformed in the most charming ways by the passage of time, gentrification, and repurposing. Lacy iron work, sturdy brick row houses, even ancient greenery and trees, seemed to beckon me, a black woman born in Cincinnati, Ohio, to sit a spell and admire them in this place that represents the starkest oppositions in my ancestral past.

That I was even in Richmond in October 2006 was the end result of a set of events that would have been improbable 15, 10 or even five years before. These events and discoveries had both confirmed my suppositions about Americans and race and stretched them to the limits of credibility.

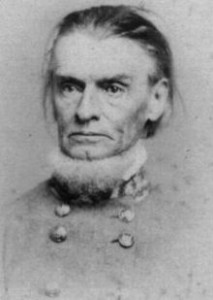

After years of research and travelling down blind alleys in pursuit of the truth of my family history, I found out that my four times great-grandfather was Henry A. Wise, the former governor of Virginia who signed John Brown’s death warrant. Brown had led an 1859 rebellion against slavery that was one of the precipitating events leading to the Civil War. Before Wise became governor, he had been a U.S. congressman, and after he left the governor’s office, Wise had been appointed a brigadier general in the Confederate Army. During all those years, Wise had a secret son (and possibly a daughter, but neither his biographer nor I have been able to verify her existence) with the only enslaved person he ever freed, Elizabeth Grey. She moved to Washington, D.C. where their son, William Henry Grey, was born free in 1829.

As a boy, Grey worked for Wise as a kind of assistant when Wise was in the U.S. Congress, and Wise provided for Grey to learn to read and write. William Henry Grey grew up to be a fiery orator and the first African American to speak at a national political convention when he seconded the nomination of U.S. Grant for the presidency at the National Republican Convention in Philadelphia in 1872. He was a Reconstruction-era Arkansas legislator who fought for the rights of ex-slaves and owned land and raised a family without ever being acknowledged by his father, even during the John Brown upheaval in 1859 when people were pleading in newspaper Letters to the Editor for Wise to pardon Brown, and one even alluded to “that mulatto boy you hold so dear.”

Wise was not under any obligation to free Elizabeth Grey nor did he have to pay for their son William’s education because racial social construction in the U.S. decreed that black enslaved people were property of privileged men, not family. Many privileged white men did favors of different sorts for their black families without recognizing them as kith and kin, and also while seeing them as members of a different race. From this practice of hundreds of years in the U.S., we have inherited and in many ways internalized the “one-drop rule” of determining blackness. The rule holds that if a person has a single black ancestor, or one drop of black blood, that person is black. It is the most restrictive definition of race in the world, and black Americans are the only group in the world subject to its strictures. Most blacks, even if they don’t know the proper term for it are aware of the one-drop rule, yet many white Americans have ambivalent or fuzzy awareness of its existence.

After Barack Obama, an American with a white mother and a black African father, was elected the first black president of the U.S., some white Americans were confused, because they saw Obama as not being black but biracial. Their confusion seemed naïve at best and dishonest at worst. Obama identifies himself as black, and they seemed not to be paying attention to him. He definitely looks black, and with visual cues being so integral to defining race in the U.S., he would never have been taken seriously by a significant portion of the electorate if he had tried to identify himself as white, like all previous presidents, or even biracial. Despite prominence of the myth of racial purity, three quarters of African Americans have European blood. Had these confused individuals never opened their eyes and seen black people around them and wondered why such variety? It almost seemed that they had to deceive themselves into voting for a black man, and the way to do that was to walk into the polls telling themselves he wasn’t really black after all. .

My family secret about Henry A. Wise, Elizabeth Grey and William Henry Grey is a perfect example of the web of privilege and marginalization created and sustained by the way our country has defined race and assigned gender roles in connection to a patriarchal system. For years, I have thought that living in the black ghettos and tenant farms of the U.S. were black people who were related by blood to the richest, wealthiest and most prominent members of white society. These wealthy men had the power to exploit sexually enslaved women in any way they wanted, even to breed more black children to make themselves wealthier. But as the one-drop rule became enshrined in laws, court rulings, economics, culture, social practices, and even religion as ironclad, it seemed to have a history so permanent that it could never be changed.

Considering his personal story, it was no wonder that when William Henry Grey was in the Arkansas legislature after the Civil War, one of the things he tried to do was prohibit the sexual exploitation of black women by white men. He proposed a law that mandated the death penalty for white men who raped black women and girls. Grey had no objection to interracial couples marrying each other out of love and free will, but as the son of a former slave, a husband and father, he lived under the constant awareness that there was nothing black men could do to protect black women. He wanted newly freed women to be protected. When one of his fellow legislators made a flip comment about the continued need to make allowances for white men “crawlin’ under the fence” every once in a while, Grey wasn’t amused. “We got to stop this crawlin’ under the fence!” he told the Arkansas lawmakers. Eventually laws in all southern states forbade interracial marriage and did nothing to protect black women from being sexually exploited and terrorized.

Considering his personal story, it was no wonder that when William Henry Grey was in the Arkansas legislature after the Civil War, one of the things he tried to do was prohibit the sexual exploitation of black women by white men. He proposed a law that mandated the death penalty for white men who raped black women and girls. Grey had no objection to interracial couples marrying each other out of love and free will, but as the son of a former slave, a husband and father, he lived under the constant awareness that there was nothing black men could do to protect black women. He wanted newly freed women to be protected. When one of his fellow legislators made a flip comment about the continued need to make allowances for white men “crawlin’ under the fence” every once in a while, Grey wasn’t amused. “We got to stop this crawlin’ under the fence!” he told the Arkansas lawmakers. Eventually laws in all southern states forbade interracial marriage and did nothing to protect black women from being sexually exploited and terrorized.

I believe that the truth will set all Americans free, but knowing the vague generalized outlines of the truth is not powerful enough to accomplish this emancipation. It’s not enough to know that many white men raped enslaved women; we need to know that many relationships were negotiated arrangements of power within a system of race and gender relations that involved its own twisted set of rules. We have not respected enough or learned enough about black women as survivors. Only when we do can we begin to appreciate the strength and the ingenuity of black women to make sure their children survived slavery. History that portrays them only as victims does not take into account their resilience or their determination. My black family is immeasurably grateful to Elizabeth Grey, even though we may never discover the exact details of her life or her relationship with Henry A. Wise.

The discovery of the heritage of William Henry Grey led to a process that culminated in the 2006 Richmond gathering of more than 70 black and white descendants from different parts of the country. After careful research, I contacted Alex Wise (Henry Alexander Wise — there are a lot of those) who happened to be spearheading the development of a Civil War museum in Richmond that would show the war from northern, southern and black perspectives. The family gathering coincided with the opening of the museum all the hoopla such an occasion demands. We toured places that had been significant to our common ancestor including the famous Hollywood Cemetery where he has an impressive memorial.

Perhaps the most discombobulating moment for me in a weekend full of them came when we stopped at the Executive Mansion of Virginia. The First Lady of the state of Virginia surprised us by welcoming us to the old house.

“It is my pleasure to welcome y’all back to the mansion,” she said in her lilting accent.

Was she talking to me? I had never been welcomed to the mansion in the first place. I noticed that white Wise descendants quietly chuckled and shared old family stories while black relatives were silent for the first time all weekend. We were all there because of history rediscovered and an attempt to reconcile the harshness of the past with the newfound perspectives of the present. Still that moment was very disorienting for me, like looking at a vista through the wrong end of a pair of binoculars.

I kept thinking about the enslaved black people who had worked in that mansion, and though I knew Elizabeth and William had not been among them, I wondered again about so many things, including how William felt about his father executing John Brown for leading a slave revolt.

I have found no evidence that Wise ever acknowledged William Henry Grey as his son. By gathering with us in Richmond, and nurturing friendships with us, some of his white descendants had chosen a dramatically different path than he chose. Fellowship and family unity reigned over our Richmond weekend. For black relatives there was so much to learn. I have cousins who are related to Calvin Coolidge and Martha Washington, for one thing. Ironically the next county over from mine here in Texas is Wise County, but I didn’t realize it was named for my ancestor. Recently, I received an invitation to descendants of former Virginia governors to a celebration of the anniversary of the governor’s mansion. One of my Wise cousins had put me on the guest list.

By the time I was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, the name William Henry Grey and the truth of his origins, was but a faint memory. I was a poor black girl with a mother using sporadic work and welfare to support our family. Never did I imagine that I was a direct descendant of one of the most famous – or infamous – figures in American history.

_______________________________________

Starita Smith is a writer, sociologist, journalist, and activist. She has been a reporter and editor at the Gary Post-Tribune, the Columbus Dispatch, and the Austin American-Statesman newspapers. She has also been a freelance journalist, including a stint as editor at the Dallas Examiner, one of many black newspapers in the city. She attended Knoxville College, Harvard University, and the University of Tennessee – Knoxville. Her master’s degree in creative writing and doctoral degree in sociology are from the University of North Texas. She is an occasional columnist for the Progressive Media Project, based in Madison, Wisconsin and her blog is at colorfulcommentary.org. She lives in Denton, Texas.

Starita Smith is a writer, sociologist, journalist, and activist. She has been a reporter and editor at the Gary Post-Tribune, the Columbus Dispatch, and the Austin American-Statesman newspapers. She has also been a freelance journalist, including a stint as editor at the Dallas Examiner, one of many black newspapers in the city. She attended Knoxville College, Harvard University, and the University of Tennessee – Knoxville. Her master’s degree in creative writing and doctoral degree in sociology are from the University of North Texas. She is an occasional columnist for the Progressive Media Project, based in Madison, Wisconsin and her blog is at colorfulcommentary.org. She lives in Denton, Texas.

1 Comment