Guided Home to Port: Assata Shakur, State Terror, and Black Resistance

By Connie Wun

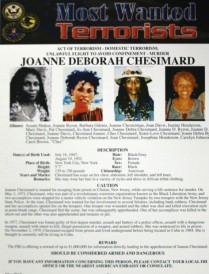

On May 2, 2013, the FBI placed Assata Shakur on its Most Wanted Terrorist list and, with the help of the New Jersey state police, has increased its reward to $2 million for information leading to her arrest. According to the FBI’s website, individuals placed on the list “remain wanted in connection with their alleged crimes until such time as the charges are dropped or when credible physical evidence is obtained, which proves with 100% accuracy, that they are deceased.”[1]

As others have noted[2], the renewed public commitment to apprehend Assata Shakur and at this scale has a number of egregious effects and implications. Scholars and activists have explored the ideological and political motivations behind this renewed attention towards Assata. For instance, professor and lawyer Lennox Hinds argued in his interview with Democracy Now! that this categorization comes on the heels of the country’s devastating experience with the Boston bombing. As the country scrambles to address fears around the nation’s security induced by the Boston calamity, it is an opportune moment for the FBI to recharge its campaign to find Assata Shakur–a Black radical woman deemed a “domestic terrorist” since 1973, a period before the lexicon of terrorism entered into today’s everyday language.

According to the FBI’s updated website, the alleged murder of New Jersey State Trooper Werner Foerster (the crime with which Assata was charged) “was always considered an act of domestic terrorism.” While it is still unclear which part of the Trooper’s death qualifies as terrorism– how he died, the context of his death (that is, that members of the Black Liberation Army were accused of killing him), or that the woman charged with his death, Assata Shakur, escaped from prison– the fact remains that Assata has recently been placed on the United States’ Most Wanted Terrorist List. As well, the facts indicate though she was charged with the murder of the state trooper, she did not commit the “crime.”

Ideally, it should register in everyone’s instinct that corralling the world to search for a 65 year-old woman based upon a case that took place 40 years ago would seem a bit excessive or unreasonable. Even more confusing and disconcerting should be the actual facts of the case. According to Hinds, “[the] allegation that [Assata] was a cold-blooded killer is not supported by any of the forensic evidence. If we look at the trial, we’ll find that she was victimized, she was shot. She was shot in the back.”[3]

That there is no forensic evidence that Assata shot and killed Foerster seems to matter little to the general public and its mass media, and even less to the FBI. Unfortunately, this is unsurprising, particularly because throughout the United States’ history, criminalizing and punishing political dissidents of color and their allies has been a part of the country’s domestic policy.

In fact, the renewed campaign to capture Assata not only obscures the role that the counterintelligence program (COINTELPRO) may have had in the events leading to her arrest, the trooper’s death, or her trial, but it also legitimizes, if not extends, the program.

Initiated by FBI director, J. Edgar Hoover, COINTELPRO was a program created in 1956 designed to discredit and neutralize political organizations and individuals deemed threats to the security of the nation. Practices included infiltration of political groups, systematic surveillance, illegal searches, fabricated criminal charges, and the orchestration of the deaths of numerous leftist activists. Those subjected to COINTELPRO included members of the anti-Vietnam War movement, the American Indian Movement, women’s movement, Communist Party, the Chicana/o movement, and Black activists including Harry Belafonte, Fred Hampton, and Dr. Martin Luther King.

Throughout her autobiography, Assata: An Autobiography, Assata details her own experiences with COINTELPRO. As a Black radical woman who criticized and resisted various forms of state violence including those against Black people in the United States and the war in Vietnam, she was falsely accused of several crimes.[4] Each case ended in dismissal or acquittal based upon lack (or clear fabrication) of evidence. The only exception, despite its own lack and fabrication of evidence, was the one involving the shooting death of Trooper Foerster.

In 1971, after documents were publicly revealed about COINTELPRO and its illegal practices, the program was purportedly dismantled. Decades later, however, evidence suggests that the surveillance practices, or at least iterations of the program, continue to exist.

Scales of Everyday Surveillance:

Scales of Everyday Surveillance:

The most recent version to come under public scrutiny is National Security Administration’s Prism and Boundless Informant surveillance programs. According to former CIA employee and whistleblower Edward Snowden, “even if you’re not doing anything wrong, you’re being watched and recorded…you don’t have to have done anything wrong,…[they will]…derive suspicion.”[5]

While it is extremely important to pay attention to how the state has created and legitimized its culture of surveillance, the heightened attention to these surveillance programs eclipses the reality that there are different registers of surveillance. That is, while everyone may be living under constant surveillance, there are scales and degrees of surveillance, which are accompanied by different sets of vulnerabilities. For some communities of color, this vulnerability manifests not only in the fact that these surveillance programs invade their privacy, but also in the ways that surveillance is often coupled with other egregious policing mechanisms that threaten their civic and civil rights.[6][7][8]

Anti-Black State Terror

The failure to connect these “new” forms of surveillance to the history of COINTELPRO obscures, if not enables, another register of surveillance that enables state-sanctioned deaths. Reaching even further back into history, sociologist Simone Browne aptly argues in an article entitled Black Luminosity and Surveillance that Black bodies have always been under surveillance and that contemporary forms of surveillance can be traced to transatlantic slavery. Browne notes that different modes of surveillance were used for racial and social domination, but were also motivated by fears over slave revolts and uprisings.[9]

The effects of current forms of anti-Black surveillance frightfully extend beyond invasion of privacy rights or civil rights. Instead, privacy rights and civil rights are increasingly becoming luxuries afforded to few in the United States and not to poor Black people. According to the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement study “Operation Ghetto Storm,” in 2012, 313 African-Americans were killed by either a police officer, security guard, or self-appointed vigilante. Most claimed or justified the extrajudicial deaths under the premise that they “felt threatened,” “feared for their life,” or “were forced to shoot to protect themselves or others.”[10] Their sense of security and safety were purportedly at risk. In the end, most were never convicted of murder, their suspicions were legitimized and authorized by the state, and their victims were never officially recognized as that– victims. On the contrary, dominant fantasies about blackness as dangerous and criminal are translated into legitimized enclosures and suspicions about Black life, subsequently authorizing anti-Black death.

This type of surveillance is also what enables a $2 million reward for the apprehension of a Black woman for something she did not do. [11] In an older letter written to Pope John Paul II, Assata writes,

At this point, I think that it is important to make one thing very clear. I have advocated and still advocate revolutionary changes in the structure and in the principles that govern the U.S. I advocate an end to capitalist exploitation, the abolition of racist policies, the eradication of sexism, and the elimination of political repression. If that is a crime, then I am totally guilty.”[12]

Responding to Terror

On May 2, 2013, the FBI deputized everyone to search, seize, and apprehend Assata Shakur—dead or alive—for a crime she did not commit. The political move to identify Assata as a domestic terrorist is more than a rhetorical strategy or an upgrade on the hierarchy of most wanted fugitives. It has placed the entire world on alert for her– the widest form of surveillance possible, one that bears death as a consequence. Categorizing her as one of the country’s “Most Wanted Terrorists” also obscures the illegal history of COINTELPRO and effectively extends its project to neutralize political movements through tactics such as criminalization, false charges, and ultimately the deaths of anti-state political activists, namely Black radicals. In her interview with Democracy Now!, Angela Davis stated that this was “a vendetta.” Indeed, the United States has long had a vendetta against anti-state violence activists, Black resistance in particular and people at large—all under the pretense of security and safety.

While it is important to examine the ways that the United States has designed its surveillance state, even more attention needs to be paid to the scales of surveillance and how lives are not only being monitored in the virtual world, but are also subject to real, concrete forms of death and dying. In her autobiography, Assata wrote, “The basis for any struggle is people coming together to fight against a common enemy” (201). It is time, yet again, for the struggle to examine who its enemy is, who is included in this struggle, what the enemy has done, if the people care, how to believe in living as Assata did, and how to fight for her life.

[1] http://www.fbi.gov/news/stories/2013/may/joanne-chesimard-first-woman-named-most-wanted-terrorists-list

[2] http://www.huffingtonpost.com/joseph-lowndes/hunt-for-assata-shakur-matters_b_3211657.html?utm_hp_ref=fb&src=sp&comm_ref=false

[3]http://www.democracynow.org/2013/5/3/angela_davis_and_assata_shakurs_lawyer

[4] http://www.daveyd.com/assataletterpol.html

[5] http://www.policymic.com/articles/47355/edward-snowden-interview-transcript-full-text-read-the-guardian-s-entire-interview-with-the-man-who-leaked-prism

[6] http://newamericamedia.org/2013/06/from-cointelpro-to-prism-spying-on-comm-of-color.php

[7]http://colorlines.com/archives/2012/07/civil_rights_groups_file_suit_to_block_arizonas_show_me_your_papers_provision.html

[9] http://www.freeinews.com/politics/black-luminosity-and-the-book-of-negroes-how-did-black-americans-go-from-slave-passes-to-supporting-wiretaps-and-domestic-spying

[10] http://mxgm.org/report-on-the-extrajudicial-killings-of-120-black-people/

[11] http://www.daveyd.com/assataletterpol.html

[12] http://www.democracynow.org/2013/5/3/assata_shakur_in_her_own_words

____________________________

Connie Wun has worked as a community educator, youth advocate, anti-prison, and anti-violence against women of color activist for more than a decade. A former high school teacher, Connie is currently a Ph.D. candidate in the Graduate School of Education at UC Berkeley. Her research interests include the politics of school discipline and punishment, racial and gender violence, psychoanalysis, and critical theory in education. Her dissertation examines the different ways that school discipline and punishment affect the lives of black and non-black girls of color. Connie’s work has been supported by the National Science Foundation, UC Berkeley Chancellor’s Office, UC Berkeley’s Center for Race and Gender, and the Haas Diversity Research Initiative. She has also published in Educational Philosophy and Theory and The Journal for Curriculum and Teaching (forthcoming).

Connie Wun has worked as a community educator, youth advocate, anti-prison, and anti-violence against women of color activist for more than a decade. A former high school teacher, Connie is currently a Ph.D. candidate in the Graduate School of Education at UC Berkeley. Her research interests include the politics of school discipline and punishment, racial and gender violence, psychoanalysis, and critical theory in education. Her dissertation examines the different ways that school discipline and punishment affect the lives of black and non-black girls of color. Connie’s work has been supported by the National Science Foundation, UC Berkeley Chancellor’s Office, UC Berkeley’s Center for Race and Gender, and the Haas Diversity Research Initiative. She has also published in Educational Philosophy and Theory and The Journal for Curriculum and Teaching (forthcoming).

0 comments