Assata: The Rose That Grew from Concrete

by Rizvana Bradley

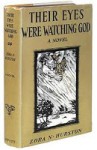

The trial scene that concludes the novel Their Eyes Were Watching God glimpses a specific form of panoptic enclosure that has given form to what Michel Foucault once called our “carceral culture.” Forms of enclosure that seized the lives of Black radicals in the ‘60s and ’70s, it seems, are sadly the inheritance of Black people more generally today. We should pay attention to the legal enclosure to which Janie is subjected, and consider Hurston a theorist of legal subjection. In Their Eyes, the legal enclosure to which Janie is subjected enacts this panoptic enclosure. Her text traces the problem of always being called, and always having to stand before the law, where the experience of the trial is itself the spectral anticipation of living a life in prison (i.e., “a step on the away to…”).

Listen to Zora’s foreboding through Janie: “First thing she had to remember was that she was not at home. She was in the courthouse fighting something and it wasn’t death. It was worse than that.” And in her opening statement at her own trial, Assata Shakur suggests that standing trial is a right reserved for the poor, for Black people, for political radicals, when she points out that President Nixon was “pardoned without ever standing trial or being found guilty of a crime or spending one day in jail.” Moreover, Assata confesses to being intimidated by the whole ordeal, boldly stating, “If you think that i am nervous, your senses do not deceive you. It is only because i know that this moment can never be lived again, and that so much depends on it.”

SO MUCH DEPENDS ON IT. Drawing out Derrida’s complex argument in his reading of Franz Kafka’s Force of the Law, Janie and Assata are forced into a confrontation not simply with the law, but, as Derrida explained, with the “enigma of being-before-the-law.” Though Janie is found innocent, she is caught up in the im/possible problem of justice. This problem, of the im/possibility of justice, is represented by an inescapable entanglement, between the law that can only supply justice through sovereign practices of decision making, and the anticipation of an authentic justice that transcends the function of law. We can conclude that the authentic, true justice that both Hurston and Derrida desire is impossible– it will never come by way of the trial, the courtroom, a “fair” jury. Real justice is a joke.

Hurston’s genius is offered in her sketch of the vernacular, a space in which themes of love, community, the rule of law, and the im/possibility of justice clash and converge. At the same time, she marks the division and violation of vernacular space by the law. On trial for the alleged first-degree murder of her husband, Tea Cake, and having been summoned before the law, specifically an all-white, all-male jury, Janie is effectively ostracized from her community, the very same one that supported and nurtured her. The love between Janie and Tea Cake is a form of common love that is disrupted by the optical arrangement of the courtroom– by spectators, both white and black, who watch Janie as she is called upon to defend her life with her one true love. Janie’s narrative, however, overwrites this, offering a tale of compassionate killing. Hurston’s text reveals precisely the “visible, invisible” structure of the Law that is not only not “accessible at all times nor to everyone,” but especially not accessible to the figure Kafka calls the countryman.[1] At stake here, at least for me, is a more abstract relationship: between the country, (a term that could possibly stand in for vernacularity), the Law, and the woman or girl who constantly mediates this distressed relation.

Beyond the threshold of the law, something else percolates– the fashioning of a common project, or simply a commons, possibilized under the rubric of care, concern, devotion, and interest. In Their Eyes, what is on trial is Janie’s love for Tea Cake, just as in Assata’s ongoing struggle, what is tried and tested is the unassailable ground of the shared history that structures black radical life. So that the relation that Assata and her legacy and inheritance affirms and upholds is not simply her friendship with Sundiata and Zayd. Assata ties together a collective will, a black radical political conviction, the very same collective desire from which she is also violently untied. The erasure of that desire, to stand together, to forge irreducible bonds and forms of relation bound by compassion, as well as calls for community that exceed “friendship” or any other term we might have to offer these essential forms of sociality, is precisely what is once again put on trial in the Trayvon Martin case, through the interrogation of Rachel Jeantel.

Rachel Jeantel: Characterized as an uneducated, overweight, Haitian immigrant teen, she has been harassed by hostile lawyers who have described her as surly, hostile, uncooperative, angry, limited, unreliable, a liar, inarticulate, and illiterate because she cannot read English in cursive.

The total and absolute negation of her person has a long history. The subjection of these women– Janie, Assata, and Rachel– to the legal system, is enabled by a particular condensation of patriarchy, colonialism, racism, and capitalism. And when it comes to black women, this matrix of oppression inevitably announces the dark legacy of black female flesh. Hortense Spillers’s theorization of the flesh as an already opened site for violence and violation is splayed across this petty courtroom drama.[2] In the Trayvon Martin/Rachel Jeantel case, we necessarily confront the ongoing reduction of the body to mere flesh, as Jeantel’s excessive corporeality, her fleshy body, is also on trial here. We know this because the public policing and “porno-troping” of feminine flesh is facilitated by the spectacularization of beauty, class, and social acceptability. And the media conflates those qualities with social ability and political relevance and heft.

Yet, as we have learned from Spillers, it is the flesh that is called upon to survive before the subject enters the juridico-political realm. And Assata Shakur’s autobiography opens with this same motif of disfigured flesh: “I was convinced that my arm had been shot off and was hanging inside my shirt by a few strips of flesh.”[3] The distressed relation between the Law and justice unfolds from the materiality of black women’s flesh, always targeted and stripped by what Foucault has called “politico-judicial powers.” The flesh is that which is in active “retreat” from the Law, to borrow Derrida’s phrasing. It knows how to survive, hide, and heal itself.

Rachel Jeantel is the bearer of a double blackness in the courtroom. On the one hand, her presence marks and bears the burden of these significations: she is conceived of and spoken about as overweight, dark, and unattractive. At the same time, her fleshy presence is precisely what bears alternative meaning and expresses itself over and against legal structures of coding and scripting bodies. Her full-bodied presence reveals precisely what it means to be legible and count as a political subject. She flips the script; stripping the “politico-judicial powers” to their minimal function, she uncovers an insidious legal lexicon, laying bare the game of the law– the way the law tarries with those who, it seems, like Kafka’s man from the country, are always only ever in front of the law, waiting for justice. Rachel Jeantel, Assata Shakur, and Janie are heroines, vernacular figures expected to live their lives waiting before the law.

Mural on the side of Marcus Books, the oldest Black-owned bookstore in the USA, located in Oakland, California

Rachel Jeantel’s belligerence, her confrontational style, is precisely that– a style that embodies a long history of resistance to the cultural, physical, and intellectual prerequisites for subjectivity. To say that she possesses style is to grant her the capacity to body forth an alternative drive. She resources a “landscape” that, as Evelynne Hammonds once suggested, would be the animating drive for black female sexual life.[4] In other words, she resources a becoming-landscape, one that expresses a life into which are enfolded “countless generations of personal sacrifice, militancy, and work.”[5] She is a rose that can grow in concrete– her practices of inhabitation and extension exceed the political demands of being both seen and heard.

[1] Jacques Derrida, “Before the Law,” in Acts of Literature, New York : Routledge, 1992, 181-220.

[2] Hortense Spillers, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book.” Diacritics 17.2 (1987).

[3] Assata Shakur, Assata: An Autobiography. (Chicago: Lawrence Hill, 1999), p. 3.

[4] Evelynne Hammonds, “Black (W)holes and the Geometry of Black Female Sexuality,” differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies, 6.2/3, 1994, 127-145.

[5] “The Combahee River Collective Statement,” accessed 7/12/13. http://circuitous.org/scraps/combahee.html.

Rizvana Bradley will be joining the faculty of the Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies department at Emory University in Fall 2013. She received her Ph.D. in the Literature Program at Duke University, with specializations in Women’s Studies and African and African American Studies, and her B.A. from Williams College, where she majored in English and Political Theory. Her research maps a specific set of gendered problematics that emerge from a tangled web of sexuality, race, and performance. She has taught courses that have addressed the intersections of race, gender, performance, and embodiment in art, literature, and culture. Her research interests include Feminist Theory, Black Aesthetics, Critical Theory, Queer Theory, and Performance Studies.

0 comments