Thoughts of My Father: Though They Had Been Drivers They Had To Be Forgiven

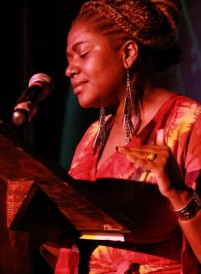

By Farah Tanis

In this country and throughout slave colonies in the Caribbean, South and Central America and Africa, drivers were those Black slaves whom with overseer status, solidified and affirmed by the whip in their hands, insured the continued enslavement of others around them.

When I was five years old my father left me for five years. I say left me because in my child eyes and mind it was just me he was leaving. Not my mother, my little sister or brother but only me. I can still recall the scent of a new garment bag swung over his shoulder. I can still feel the warm tropical air on my wet face, salted with tears and my little hands clenched at the end of my long arms around his bearded neck. I was devastated. My screams just got louder as he put me back down on the floor where right then, I refused to stand on my feet. My body trembled with grief as my mother and grandmother held me back as I watched my crying father disappear behind airport glass doors. I would not see him again for five years.

To the average onlooker, stranger, witness to that day, it could be supposed that my father like many other fathers I’m sure, was a man experienced by his kin and by his family as kind. One could assume he was friendly and they could suppose he was peaceful, but my tears of love for my father vanishing before my eyes had prior to that day, and more often than not, been tears of dread. My father had in fact been an extremely violent man who often flew into fits of rage and anger, cunning, unforgiving and often completely, emotionally contorted out of shape.

After that day at the airport, the day I saw my father crying for the first time, a man who mastered the art of estrangement and isolation even as he stood three-feet away in the same household, I committed to getting to know him. At five years old I threw myself into researching who my father was by writing him letters, drawing him pictures, recording my voice and telling him stories of my long days, weeks and months in the tropical sun that he would receive by mail. For years, I went on an inquisition and campaign and asked my mother, my grandmother and even investigated strange bearded men who reminded me of him. I was on a quest to begin to truly see my father, and see my father I did, eventually.

You see, my father was a first born son, rejected by two parents who consistently unloved him. They broke his little body with all sorts of violence against a boy who simply wanted to belong to a pack, a tribe, and wanted to claim for himself what his heart knew was his inheritance by virtue of the fact he was human—love, shelter, food, safety, education, respect and recognition. They broke his little soul much in the way masters broke the souls of slaves who belonged to everyone and yet no one. Contorted out of shape for the rest of his life my father exacted violence, fed on fear, power and control. He maintained the patriarchal status-quo and became the slave driver he was trained to be. He did this by ensuring all those around him remained subordinate, slaves like him who had a difficult time seeing in one another, any pain, need, longing, love and humanity.

By truly seeing him and only in truly seeing him—who he had been, who he was when he left me at five years old, when we reunited shortly before my tenth birthday and after his passing in the spring of my twenty-fifth year, was I able to forgive him. My father who had missed his inheritance because he was broken out of shape, for him alternative ways of being a man, sounds of remote possibilities of liberation fell on deaf ears. The total rule of the fathers—such is patriarchy, became all he could be. He became all he had been given. He became violence and withholding. He became breaking, power and control. However, for all those years he lived as a slave I forgive him. For all those years he committed to being a maker of slaves, I forgive him.

In this country and throughout slave colonies in the Caribbean, South and Central America and Africa, there were drivers. Drivers were those Black slaves whom with status solidified and consistently affirmed by the whip in their Black hands, insured the continued enslavement of others around them.

Yet, when the ring shouts of freedom had sounded in the land and reached the slave quarters, whether by emancipation proclamation or whether that freedom had been taken by force or by their own hand, a choice had to be made among the freed Africans. Is a driver a slave or is he a master? Is he entitled as are the rest of us to freedom, or do we deny him what is really ultimately his inheritance? A political and yet very personal decision had to be made in those fateful days as it has to be made today—to leave no one behind enemy lines. Though they were drivers they had to be forgiven. They had to come along and they had to do so under no threat of death, harm or retaliation. For that to be possible, though they were drivers they had to be forgiven.

I constantly dedicate my work in the Black feminist movement to my father, to my mother, my experiences alone and in collective community and I ground it in forgiveness, intentionally in the practice of forgiveness as resistance. For Black people, for Black women this practice is to engage in extraordinary acts of freeing oneself, extraordinary leaps towards healing, extraordinary steps in revolution and forms of liberation where even those who’ve caused harm must come along. It is a practice in investigating when and where it is we lost ourselves and each other, and a practice in what I was told an elder African sister referred to as seeking to “understand the whys so that we can come up with better hows.” That type of forgiveness calls into question entire ways of being and existing. It challenges, unhinges and dislodges the very foot of patriarchy and racism not only off our necks but off the necks of even those who practice slave driving. That kind of forgiveness is to truly recognize the humanity in all of us.

As with my father, though they had been drivers they had been forgiven by thousands if not millions who had to transit out of plantations everywhere. When they began to take leaps towards healing and began to march towards freeing themselves, a conscious decision had to be made by these foremothers and forefathers in this great process of getting free—that they all deserved to be free, to be unbent and their world reshaped. Those are the shoulders on which we stand. Many have heard it said and many have learned first hand that “we are not the sum total of our oppression” and that it is impossible not to long for some kind of freedom. In addition, through my father I also learned that it is impossible not to be able to love.

_______________________________________________

Farah Tanis is the co-founder and Executive Director of Black Women’s Blueprint, a national Black feminist organization anchored in the U.S. Tanis is a 2012 U.S. Human Rights Institute Fellow and served the past 7 years as Almoner for the Havens Relief Fund providing small grants to New Yorkers in need. She has been on several Boards including Right Rides for Women’s Safety and Haki Yetu working to end Rape in the Congo region of Africa. Tanis is the founder of the Museum of Women’s Resistance (MoWRe) dedicated to presenting the diversity, dynamism, and global influence of women of African descent in the realms of family, work, community, nations and the natural environment. She is the creator of Mother Tongue Monologues, a vehicle for communicating Black feminist praxis at the grassroots and for addressing Black sexual politics in African American communities. Her body of work includes the production and contribution to several grassroots and international films, curricula and human rights policies.

Farah Tanis is the co-founder and Executive Director of Black Women’s Blueprint, a national Black feminist organization anchored in the U.S. Tanis is a 2012 U.S. Human Rights Institute Fellow and served the past 7 years as Almoner for the Havens Relief Fund providing small grants to New Yorkers in need. She has been on several Boards including Right Rides for Women’s Safety and Haki Yetu working to end Rape in the Congo region of Africa. Tanis is the founder of the Museum of Women’s Resistance (MoWRe) dedicated to presenting the diversity, dynamism, and global influence of women of African descent in the realms of family, work, community, nations and the natural environment. She is the creator of Mother Tongue Monologues, a vehicle for communicating Black feminist praxis at the grassroots and for addressing Black sexual politics in African American communities. Her body of work includes the production and contribution to several grassroots and international films, curricula and human rights policies.

4 Comments