Gender Policing the Vegan Woman

By Corey Lee Wrenn

I have always used my Facebook account as a tool for social activism. Opening up oneself to the public world of the internet—a space created by men for men—can be dangerous for any woman. The vegan woman, however, meets with added challenges.

Most of my anti-speciesism posts drew angry or paternalistic male friends and acquaintances determined to explain to me what was wrong with my posts and what was wrong with me for posting. I was often accused of hostility or mental illness because of my straightforwardness about the oppression of Nonhuman Animals. I noticed my posts about rape culture and pornography met with similar reactions from male users. Strangely, posts about racism, classism, and labor rights (arguably more gender-neutral topics) received little or no attention at all. It seemed I was constantly debating men who were determined to police me on how to be a proper advocate (or, rather, a proper lady) for issues that challenged their privilege.

Yet, I also found support in Facebook. Facebook gave me a doorway into the wider vegan community. I was able to network and collaborate with activists all around the world. Of course, as with any internet space, trolling was an issue, as was fierce in-group/out-group boundary maintenance. It was not until I became outspoken about my support for intersectionality and my opposition to violence that I began to suspect my negative interactions with fellow activists were actually reflective of patriarchal oppression too.

At first, I thought it was simply a conflict of theoretical backgrounds. I had collaborated heavily with a male-led grassroots organization that prides itself in a “rational” approach to anti-speciesism. After about a year of endless debates that ended in my being branded “irrational,” I severed ties with the group. I had dared suggest that women’s experiences matter to any campaign meant to end oppression. I had dared suggest that perhaps women themselves would be best suited to sharing those experiences and giving them meaning. Feminism, they declared, was an insult to the rational anti-speciesism project.

Some months later, I wrote a piece for my blog condemning the patriarchal hijacking of feminism. A prominent theorist had declared on his Facebook fan page that 1. Men can be feminists, and to suggest otherwise is sexist, and 2. Only vegans can be feminists. In other words, men were once again, defining feminism. The response I received from my piece was overwhelmingly negative . . . and male. In taking on the feminist cause, I had overstepped my boundaries as a woman in a men’s movement.

Being a vegan creates certain difficulties and discomforts for self-identified women. Caught between a rock and a hard place, vegan women often experience male backlash by rejecting the patriarchal project of speciesism, but they also struggle for respect in the male space of social movements. Protesting the exploitation of other animals (a relationship of power and dominance) is, regardless of gender, a feminist action. On the other hand, shaping culture and advocating for social change remains very much a masculine endeavor.

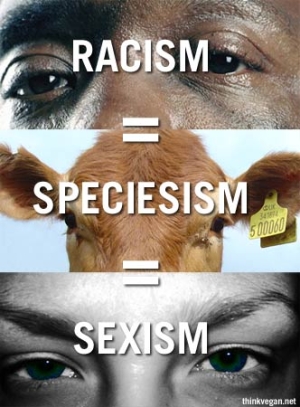

Vegan feminist Carol J. Adams has noted that the exploitation of Nonhuman Animals[i] is a patriarchal oppression. To use the bodies of vulnerable groups for one’s pleasure or convenience is an extension of male-on-female violence. Hunting, slaughter, and vivisection–three of the top institutions of Nonhuman Animal exploitation–are staffed primarily by men. The ideology of eating flesh, wearing flesh, testing on unconsenting sentient beings, and imprisoning or hurting sentient beings for entertainment is an ideology of dominance.

Women’s role in this systemic oppression tends to be one of compliance and largely a reflection of her own oppression. In Brutal: Manhood and the Exploitation of Animals, Brian Luke suggests that women are often bound to participation in the project of speciesism by cooking “meat”[ii]-based meals that appease the family patriarch. The litany of cosmetics and animal skin garments marketed to women, too, are thought to be bound to men’s privileged status. Women adorn themselves with beauty products to fill their role as objects for the male gaze. “Fur” is often purchased by men for women as a means of demonstrating his status.

Of course, many women have wielded some degree of power in this “subservient” role. Women have been credited for popularizing the natural foods movement through their strategic position as the primary food purchaser and preparer. Likewise, women’s products are many times more likely to be free of animal testing. While men may have been the primary breadwinners, women were often the primary consumers. Advertisers paid attention, and this granted women considerable influence.

While many women are locked into the project of patriarchy by powerful socialization processes, others have tapped into feminine stereotypes to express concern for other animals in a way that is more or less socially accepted. Women are thought predisposed to nurturing with an affinity for the natural world, and this conception allowed women of the Progressive Era to enter the public sphere of social advocacy as “nature’s housekeepers.” This association between women and nature is thought to account for the large female constituency (about 80%) in the Nonhuman Animal rights movement today.

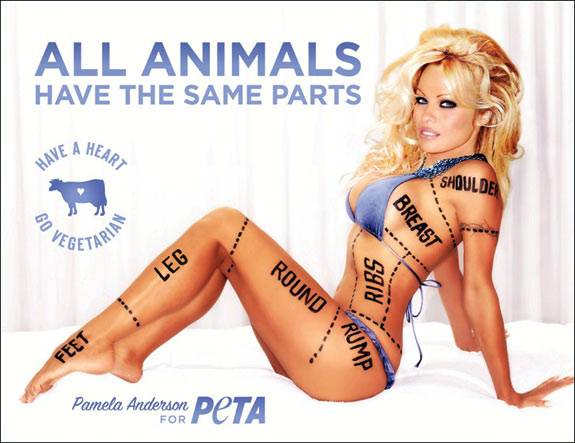

Certainly, these stereotypes can be limiting. Female advocates are often funneled into non-threatening advocacy like shelter work. Most are confined to mundane tasks behind the scenes and many are encouraged to go naked in public protests and advertising campaigns. Women who step beyond these boundaries of gender-appropriate advocacy often face vicious retaliation. The same qualities that men are commended for—directness, leadership, initiative, strength—are applied negatively to outspoken female activists. These women are repackaged as overbearing, loud, obnoxious, and crazy. In a word, they become unfeminine.

The role that gender plays in the interactions between Nonhuman Animal rights advocates, the public, and counter-movements has not gone unnoticed. Sociological studies have shown that many campaigns fall flat partly due to gender stereotypes that interpret female advocacy as overly emotional, irrational, and ignorant of the “necessity” of exploitation. As a result, the Nonhuman Animal rights movement has tended to glorify masculine tactics (rational suasion and direct action) and downplay feminine tactics (intersectionality and nonviolence).

Professor Steve Best of the Animal Liberation Front, for instance, is sharply critical of nonviolent approaches, or what he calls “pacifism.” Peaceful vegan education, he warns, is aiding the exploiters and facilitating institutions of oppression. In recorded lectures where Best loudly asserts the merits of vandalism, threats, and physical assaults to rooms full of women, one can’t help but wonder if his real issue is with the feminization of animal advocacy.

Advocating on behalf of other animals is a political protest that is often hugely influential to a woman’s self-identity. But to challenge the institution of animal use is to challenge the institution of male dominance. On one hand, women who take on “masculine” traits in their advocacy are met with hostility. On the other, women who perform their gender “appropriately” are not taken seriously due to their femininity. Many academics have been critical of PETA’s sexual objectification of female advocates, but only a handful has discussed the sexism that structures the movement as a whole. Even fewer on-the-ground advocates have touched on gender discrimination and policing. For the most part, the female experience is omitted from animal liberation discourse.

Race politics, too, tend to go ignored in Nonhuman Animal rights claimsmaking. A June 6, 2013 post on an anti-speciesism website, Free From Harm, urges readers to “help stop the practice of ‘live sushi’,” which they call “barbaric,” “vulgar” and a “shame to the Japanese people.” I responded with the suggestion that such a campaign reinforces structural racism. Sensationalizing particular acts of cruelty committed by people of color encouraging prejudice and facilitates a sense of white superiority. I received a response very similar to my work against sexism. Advocates, who were mostly white, attacked me viciously, accusing me of “playing the race card” for intentional trouble-making. One even diagnosed me with a mental disorder.

While race plays an important role in the repertoire, people of color are often tokenized. That is, especially atrocious manifestations of racism (like slavery) are drawn upon to make a case for anti-speciesism. Yet, as Dr. Breeze Harper has theorized, the current experiences of people of color are ignored or denied in vegan outreach efforts. Major organizations pay little to no attention to the reality of environmental racism, food deserts, and ongoing human abolitionist advocacy. While Harper and other vegan women of color have been vocal about this marginalization, the Nonhuman Animal rights movement tends to operate as though in a post-racial society where enslavement and discrimination are a thing of the past. This post-racial position presumes that everyone has equal access to vegan alternatives and present-day people of color are disconnected from their history of colonization and racism.

History has shown us that women can prove a powerful force in advocating for social change. Yet, in the social movement arena, what tactics and measures are considered legitimate and helpful are still managed closely by men (and the women socialized to support them). The Nonhuman Animal rights movement has an added layer of complexity in that speciesism is an offshoot of patriarchy and the movement itself maintains a patriarchal hierarchy of command. Policing femininity and omitting feminist critique has the unfortunate consequence of reinforcing sexist stereotypes and limiting women’s potential contributions. This omission makes building bridges to other social movements difficult. Ultimately, the movement’s conception of oppression is fragmentary and anti-speciesism is left anything but inclusive.

Corey Lee Wrenn is an instructor of Sociology and Ph.D. candidate with Colorado State University in Ft. Collins, Colorado. She received her B.A. in Political Science from Virginia Tech in 2005 and her M.S. in Sociology from Virginia Tech in 2008. Her research interests include social movements and critical animal theory.

Corey Lee Wrenn is an instructor of Sociology and Ph.D. candidate with Colorado State University in Ft. Collins, Colorado. She received her B.A. in Political Science from Virginia Tech in 2005 and her M.S. in Sociology from Virginia Tech in 2008. Her research interests include social movements and critical animal theory.

4 Comments