I’m Complicated, Just like Feminisms: A Black and White Feminist Working It Out (Part I)

Dr. Connie Ruzich and I first met soon after I walked onto the Robert Morris University campus in 1999. I thought I’d become a Finance & Economics major. Then, I thought I’d become an Accounting major. Then, I thought I’d become a Mathematics major. Then, I thought…you get the point. I changed my major seven times as an undergraduate. As a result, while most of my peers were taking “easy” electives during our senior year, I was taking six required classes each semester (two more per term than what was considered full-time). Throughout all of this typical undergraduate chaos, I found myself taking English classes more than anything else. Really, it wasn’t just that I was taking English classes. I was taking classes with Dr. Ruzich. She was amazing. And she was hard. I tell my students all of the time that she would fail any essay in which the writer committed more than an average of seven grammar and mechanics mistakes per page. I haven’t been able to truly implement that policy yet, and don’t know if I ever will be. Still, even with such a difficult policy in place, I scored well on all of the essays I wrote in her classes. She was that good. She pushed me to be the best writer I could possibly be. It was actually Dr. Ruzich who convinced me that I should become a college professor. After she agreed to be my advisor, I told her that I wanted to become a high school English teacher. At that moment, she reminded me of a time during one of her classes when I got so frustrated with another student that I pushed over a chair. She might say that I threw it. While remembering that, she said, “You should either become a middle school teacher or college professor.” We both had a good laugh and agreed that teaching high school might not bode well for me or the students.

I write all of this to emphasize that Connie (she demanded I call her that after I earned my Ph.D.) and I go way back. She’s seen me at my best and my worst. I included her in the acknowledgements of my dissertation, because she saw me where I am before I even knew the place existed. She didn’t know up until this very moment—on purpose—that I am a feminist, in part, because of her. For this reason, I thought it would be tremendous to include a conversation between us, a black and white feminist, in this forum. Since we reconnected over social media a few years ago, we’ve had several conversations about the ways in which gender, race, socioeconomic status, and age intersect and shape our experiences. Hence, I wanted to share that with The Feminist Wire readers. This forum is an especially significant space in which to share that conversation, because we hope to model for our readers just one of the many ways in which feminists can reconcile their differences through healthy, constructive discourse. So, we started out the conversation by asking one another to describe our first encounters with feminism and how our definitions have changed over the years:

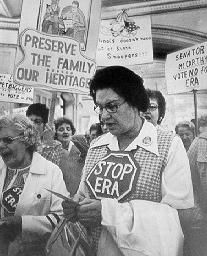

CONNIE: The first encounter with feminism that I remember was an odd mix of national politics and personal experiences: it was sometime in middle school when there was a lot of talk about the Equal Rights Amendment (1972). Where I lived (a small farming community, population less than 2000, where my next-door-neighbor grew 1/3 of the nation’s beet crop and my dad was a cow-breeder), the ERA was the Evil Rights Amendment. I remember buying the line that if this horrible law was passed, it would overturn normal society as we knew it and — get this — there would be NO SINGLE SEX BATHROOMS. They’d be illegal — as everyone would be equal. It sounds ludicrous now, but I remember being utterly convinced. And just a few years later, I was having a really hard time in my personal life negotiating soon-to-be womanhood. For example, no one wanted to date me (my best friend confided sympathetically in my junior or senior year that she believed I’d never marry — I was just too nerdy-smart to get a guy), and I was having a really hard time at church in the youth group. All the boys got to shoot baskets with the pastor and do really cool things — while the girls got to bake for the guys so when they were done they had food. It was the same in school sports — the only “sport” available for middle school girls was cheerleading. So that’s what I did. And when I got to high school (where we could play basketball or field hockey or softball), there was one uniform that was used for every sport: polyester shorts and a polyester t-shirt. For basketball, you wore it as it was. For playing field hockey outside of Buffalo, New York in November, you wore everything you could fit under it. For softball in spring, you layered for warmth — and so you didn’t tear the skin off your thighs while sliding into base. But the boys’ teams: well, every sport had a different uniform (imagine that?!), and at some point it really struck me: the boys’ basketball team got WARM UPS — really nice ones, just for those minutes before the game. I remember being absolutely infuriated by the injustice of it all. I was ANGRY — and hurt. I didn’t call myself a feminist yet, but I started looking for things to read, and somehow (no memory at all of how), I stumbled upon Germaine Greer’s The Female Eunuch and read it in high school, probably my senior year. That’s when I could put a name to the problem — patriarchy — and that’s when I self-identified as a feminist. I don’t remember anything of what GG said (I had to look the book up before we started this conversation), but I remember she was angry, and she was angry for women.

Since then, my ideas have evolved again through the curious mix of politics and life experiences. I’m a Christian who has attended evangelical churches nearly all my life — and I still do. Whew. That’s not been easy. But I’ve found sensible and compelling Christian feminists, particularly in Elaine Storkey and Mary Stewart Van Leeuwen. I’m now married and have two daughters in their early twenties, and I continue to notice structural and cultural ways in which girls and women are limited by their gender and the ways in which women are (in my world) largely defined by their married status or their marriageability. And I work in academia, perhaps the last stronghold of the Old Boys Network. Come to think of it, the Old Boys Network is a lot like my experiences of middle and high school. My world has gotten somewhat larger with respect to racial and cultural diversity – I’m no longer in a farm town — but not a lot larger.

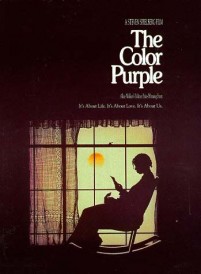

HEIDI: If I had to pinpoint it, I would say that my first encounter with self-defined feminism was when I first saw The Color Purple on television. The novel was released in 1982, when I was just a year old. But I remember growing up and seeing the book in my paternal grandmother’s, my Grannymoll’s, house. I also remember watching the film with her throughout my childhood. Of course, I didn’t know that I was experiencing feminism at that time. I didn’t even know the word, and I don’t recall any women in my family using. But I definitely knew what strong and powerful women looked like, not just because of the film but because of the women in my family that I watched every day growing up, especially my maternal grandmother, my Nana.

In addition to The Color Purple, my Grannymoll had a lot of books written by black women around the house. So, by the time I got to college, I had already read Terry McMillan, Alice Walker, Zora Neale Hurston, Gloria Naylor, and Toni Morrison. I actually remember taking your African American Literature class the first time you taught it, in 2002 or 2003. The funniest thing happened when you assigned Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston. The entire time I was reading it, I kept thinking and saying, “I think I’ve read this before!” Come to find out, I had read that novel when I was just seven or eight years old. Events like that definitely shaped my view of feminism. Feminism for me has always been grounded in intersectionality, examinations of how race, gender, age, religion, and socioeconomic status intersect. That’s what the women I was reading were thinking and writing about. And even though no women in my family used the word “feminism,” that’s what they were thinking and talking about.

In addition to The Color Purple, my Grannymoll had a lot of books written by black women around the house. So, by the time I got to college, I had already read Terry McMillan, Alice Walker, Zora Neale Hurston, Gloria Naylor, and Toni Morrison. I actually remember taking your African American Literature class the first time you taught it, in 2002 or 2003. The funniest thing happened when you assigned Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston. The entire time I was reading it, I kept thinking and saying, “I think I’ve read this before!” Come to find out, I had read that novel when I was just seven or eight years old. Events like that definitely shaped my view of feminism. Feminism for me has always been grounded in intersectionality, examinations of how race, gender, age, religion, and socioeconomic status intersect. That’s what the women I was reading were thinking and writing about. And even though no women in my family used the word “feminism,” that’s what they were thinking and talking about.

I probably heard the word used for the first time in the media. I, like so many others, learned that feminism was a “dirty word.” Still, that was attractive to me! Every time I would hear something negative about feminism, I would think, “Those are the kinds of women I love! That is the kind of woman I want to be!” I wanted to be strong, smart, vocal, and aggressive. I wanted to agitate for justice. I didn’t see anything wrong with that. Every strong woman I ever loved and respected, whether I knew them personally or not, was all of those things.

Add to this the fact that my father is a blues musician. So, when I spent time with him, I was gaining access to hardcore blues women like Koko Taylor, and she’s singing about folks getting into violent fights at a juke joint! I loved that kind of stuff because in addition to strength and aggression, it’s honesty and vulnerability. I loved the fact that it was raw and real. So, even before I really understood the word feminism, I wanted to be the kind of woman that embodied all of those characteristics.

CONNIE: I’m really struck by the ways for you in which feminism was strong and powerful and positive — all bound up with reading and with women you were close to. Funny, but despite having a strong grandmother and mother, they weren’t ever part of my experience of feminism. My grandmother was a divorced single mom with seven kids to raise, poor as dirt, her ex-husband was an alcoholic, so she washed dishes in a diner for years. She was strong, and she was a survivor — but she was never mouthy. She was all about The American Dream and hard work ethic — very German — and I can’t think of anything or any time at which my mother or my grandmother thought about societal structures as any part of their problems or challenges. They seemed more ready to blame themselves when their marriages and lives didn’t work out.

And I think that when I was young, I was much more naive in my understandings of feminism than you were. You say that you were always aware of the intersections of “race, gender, age, religion, and socioeconomic status.” I simply wasn’t — and still am not to a large extent. Perhaps being white and privileged, when I’m denied access to male privilege, I tend to blame myself. I wonder if many white women do this — because we’ve internalized the American Dream to a much larger extent? So that when we are denied access to male privilege, we believe that maybe we aren’t working hard enough, or we’ve made bad decisions, or we’re not good enough in some other way.

HEIDI: Those are interesting thoughts, which, believe it or not, made me think about my Nana, arguably the strongest woman in my life growing up. She was actually married and eventually became the First Lady of my Papa’s church, and she was mouthy! She was a critical thinker, too! She worked, and believed that all women should work, especially if they were poor. Interestingly enough, she had very conservative views about race, gender, and sexuality. She and my Papa were the new black middle class. She had migrated to Ohio from Mississippi with her family during what we now know to be “the Great Migration,” and she was very hard on black folks that she didn’t feel worked hard enough, as she and my grandfather had. She had issues with black women wearing “nappy” hair and unmarried black women having children and things like that. You know, before I ever knew the term “politics of respectability,” I was especially familiar with it because of my Nana. Still, I attribute a lot of my feminism to her.

CONNIE: Here’s another part of your narrative I love: “Those are the kinds of women I love! That is the kind of woman I want to be!” I wanted to be strong, smart, loud, and aggressive. I wanted to agitate for justice. I didn’t see anything wrong with that. Every strong woman I ever loved and respected, whether I knew them or not, was all of those things.”

WOW. My mom was known as mouthy and a fighter — and many of the bad things that have happened to her we’ve all said were due to this. In implicit and explicit ways, I’ve been told over and over again by women and men, “Be quiet, play along, fly under the radar to affect change. Rushing the barricades is foolish and suicidal.” The problem is, I’m too much like my mom — we’re mouthy fighters who can’t resist a good barricade rush. Also, I like the fact that a woman who had what some might term “anti-feminist” positions still modeled feminism for you.

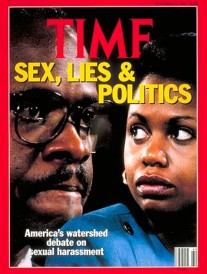

HEIDI: Along those lines, I remember the Clarence Thomas and Anita Hill case, which broke when I was just ten years old. I remember my family having intense discussions about this case, and the views coming from a lot of the women in my family were NOT exactly feminist. From what I remember, there was a lot of victim-blaming directed at Anita Hill. So, even though the women in my family were strong and intelligent, they still held tightly to a lot of arguably conservative, patriarchal, and racist values that are detrimental to people of color, especially women. This is reminding me of Nella Larsen’s short story “Sanctuary.” What would compel the black woman in that story to hide the black man who murdered her son from the white police officers? Even though her son has died, she’d rather let his murderer go “free” than to hand him over to white police officers that are sure to torture or even kill him. The ways in which black women have protected black men, even when it was detrimental to our own spiritual, mental, and emotional health, these are things that I grew up seeing and thinking about. This, at least in part, explains why the women in my family were skeptical of Anita Hill. For them, she was about to hand over a black man to the white police officers. They didn’t really complicate it beyond that at the time. On the other hand, I could give you all kinds of examples of the black women in my family not “taking any shit” from black men. Complicated stuff.

CONNIE: I’m thinking through your comments on the Anita Hill case — and perhaps because I don’t feel the need to defend black men in the way black women do, I remember that I was outraged by his behavior — and by the defense he got from the conservative men I know. Perhaps it’s easier for white women to blame men, that is, there isn’t the same need to defend white men because in our lived experiences, men are privileged and powerful enough to defend themselves?

HEIDI: I know a lot of black women were outraged by his behavior, just not many women in my family or immediate circle. Later, I went on to read black feminist writing, and they cut Justice Thomas NO slack for his behaviors. However, what they were willing to do that white feminists either wouldn’t or couldn’t do, was spend time carefully and critically theorizing black folks’, especially black women’s, responses to the case, even if they weren’t exactly feminist. It was, and still is, important for black feminists to be careful when black folks are thinking and discussing things in ways that are healthy for our communities, even if it doesn’t feel healthy at the time. It is our duty to learn from our communities as much as we hold ourselves responsible for teaching them. In this way, black folks are communal, at least in part, because of racism. In “A Black Feminist Statement” (1977), the Combahee River Collective writes, “We struggle together with Black men against racism, while we also struggle with Black men about sexism.” I think white feminists have only recently begun this work with white men, at least as deliberately as feminists of color have for many decades. I don’t know if it’s easier for white women to blame black men, as you suggest, but I think it is easier for some white women to forget about the ways in which black people are committed to one another because of the issues we’ve faced regarding race and racism. This, of course, isn’t true for all black people, but it helps to explain some of the reasons why black folks were especially skeptical of Anita Hill.

CONNIE: I think that what you wrote here is really important: “However, what they were willing to do that white feminists either wouldn’t or couldn’t do, was spend time carefully and critically theorizing black folks’, especially black women’s, responses to the case. It was, and still is, important for us as black feminists not to be so easily dismissive when black folks are thinking and discussing things in ways that are healthy for our communities.”

Yes, as our first responses seem to have demonstrated, we live in communities, and our feminism emerges out of our engagement with those communities. And that makes our feminisms different — and those differences are immensely important in making our feminisms valid for us. You’re right — I couldn’t begin to fully or adequately critically theorize black folks and black women’s responses to the case. That’s why I need you; that’s why I need to listen to you.

HEIDI: I think you’re selling yourself short. I read a lot of black women’s writing during my childhood. However, the first time I was given the opportunity to examine black women’s writing in an academic space was your African American Literature class! On the first day of class, you said something like, “I’m mostly trained in writing, but if I don’t teach this class right now, I don’t know who can or will.” You were smart, brave, and so very careful. I don’t want to put forth an unnecessarily essentialist argument that white women can’t study black women. Given the small amount of professors of color, especially women, that line of thinking would be detrimental to our work. I’m pretty sure that’s one of the reasons why our work isn’t being taught in the ways it should be. It’s almost like a cop out that I think white feminists have depended on for too long. “I can’t teach black feminist thought, because I don’t feel I’d be qualified to do so.” I’m not buying it. You did it, Connie, when you taught that African American Literature course. I do it when I teach LGBTQ theory in my courses. We have to challenge our privileges and take risks by reaching beyond ourselves to do the work. I don’t want to suggest that Standpoint feminists are completely off-base in suggesting that there’s something unique about a person’s sociocultural location and the studies they undertake, as well as the ways they teach. I just don’t want to hear that as an excuse to keep perpetuating the marginalization of the work.

CONNIE: Good point — I don’t like the essentialist argument either. But let me respond by saying that I couldn’t have taught that course with any real integrity to a class of white kids. The black students in that class filled in with experience and situated community-ness what I couldn’t deliver. That’s what I meant when I said I couldn’t “fully or adequately” — with the emphasis on “fully.”

I think, however, you’re right in that many of us think “not my feminism, not my problem” — so let the black feminists do their thing, the LGBTs do their thing, the Latinos do their thing, the conservative feminists do their thing, and on and on. We all need to be better at learning about and listening to one another.

HEIDI: I definitely get that. However, let’s think about it in another way. I had a professor in the English Department at Ohio University that taught Spenser and Milton. Even though she was white, what would she know about living in London in the 16th and 17th centuries as a white man? I think that even when we can’t “fully or adequately” understand that which we’re studying or teaching, we can do so with a kind of love and care that is significant. Thankfully, there are some texts that address the kinds of concerns we’re discussing here. I’m thinking specifically of White Scholars/African American Texts edited by Lisa A. Long, for example. So, there are definitely ways that we can overcome the challenges we face in order to move forward, healthy and constructively.

Stay tuned for Part II of our conversation, to be published on Monday, April 29!

Heidi R. Lewis is an Assistant Professor of Feminist & Gender Studies at Colorado College. Her teaching and research focus on feminist theory, gender and sexuality, Black Studies, Critical Media Studies, Critical Race Theory, Critical Whiteness Studies, social justice, and activism. Her essay “An Examination of the Kanye West’s Higher Education Trilogy” is featured in The Cultural Impact of Kanye West, and her article “Let Me Just Taste You: Li’l Wayne and Rap’s Politics of Cunnlingus” is forthcoming in the Journal of Popular Culture. She is currently in the process of completing articles that examine Rihanna’s “Pour It Up,” as well as FX’s The Shield. She has given talks at Kim Bevill’s Gender and the Brain Conference, the Frauenkreise Projekt in Berlin, the Educating Children of Color Summit, the Sankofa Lecture Series, the Motherhood Initiative for Research and Community Involvement, the Gender and Media Spring Convocation at Ohio University, and the Conference for Pre-Tenure Women at Purdue University, where she earned a Ph.D. in American Studies (2011) and a Graduate Certificate in Women’s Studies (2008). Heidi has also been a contributor to Mark Anthony Neal’s NewBlackMan, NPR’s “Here and Now,” KOAA news in Colorado Springs, and KRCC radio (the Southeastern Colorado NPR affiliate), and she was featured as a Racialicious “Crush of the Week.” She and her husband, Antonio, live in Colorado Springs with their two children, AJ and Chase, and their cat Max. Learn more by following Heidi on Twitter at @therealphdmommy and by visiting her FemGeniuses website.

Connie Ruzich is a University Professor of English at Robert Morris University, where she teaches linguistics, literature, and education courses. She earned a Ph.D. in Writing at the University of Pennsylvania and a Masters in Literature with a concentration in Composition and Rhetoric at the University of Pittsburgh. Her research examines the various ways in which language use and practices shape identities, from white students’ resistance to the study of multicultural literature to Starbucks’ appeals to the language of love in their corporate advertising. She is currently working on a scholarly examination of dialect in Stockett’s novel The Help.

0 comments