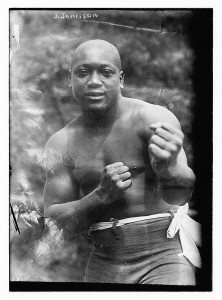

Op-Ed: Jack Johnson and the Racial Politics of a Presidential Pardon

On March 5, U.S. Senators Harry Reid (D-NV), John McCain (R-AZ), William “Mo” Cowan (D-MA) and U.S. Representative Peter King (R-NY) put forth a resolution to pardon Jack Johnson, the first-ever black world heavyweight champion from 1908 to 1915. The legislation calls on President Barack Obama to posthumously pardon Johnson for his unjust conviction under the federal Mann Act on May 14, 1913, almost a century ago.

On March 5, U.S. Senators Harry Reid (D-NV), John McCain (R-AZ), William “Mo” Cowan (D-MA) and U.S. Representative Peter King (R-NY) put forth a resolution to pardon Jack Johnson, the first-ever black world heavyweight champion from 1908 to 1915. The legislation calls on President Barack Obama to posthumously pardon Johnson for his unjust conviction under the federal Mann Act on May 14, 1913, almost a century ago.

Passed in 1910, the Mann Act barred the interstate transport of women for “prostitution or debauchery” and “other immoral purposes.” However its language was so vague that white prosecutors often used it as a political tool to punish black men who dared to fraternize with white women.

Infamous for his high-profile relationships with white women, Johnson had the book thrown at him in an era when laws prohibiting interracial marriage were the rule across much of the nation. Facing a 366-day prison sentence and a $1,000 fine, Johnson fled the country in protest, and spent the next seven years in exile abroad. When he finally returned in 1920, he still had to serve a 10-month sentence at Leavenworth Penitentiary.

Let me be clear. I fully support a posthumous pardon for Johnson. There is simply no evidence to suggest that he unlawfully took any women across state lines for the purposes of prostitution. It was a racially motivated conviction, plain and simple. And, it is about time that Johnson had his name officially cleared. After all, Johnson was the first to seek clemency on his own behalf. In a letter to Attorney General Harry Daugherty on March 25, 1921, Johnson avowed his innocence and declared that his sham of a trial had made “flagrant appeals to passion, race hatred and moral infamies.”

However, what I am much more wary about are the motivations and sentiments behind this recent resurgence of the pardon campaign. Most popular press on Johnson’s pardon continues to cast it as a potential salve for the United States’ historic racial divide–a potent symbol of the dawn of a post-racial era. I fear that this framing of the pardon movement will reduce Johnson’s complicated, global legacy to a simplistic symbol of contemporary American colorblindness.

Indeed, if you examine Johnson’s life in all of its complexity, it points to something much larger than just the unfairness of his historic Mann Act conviction. It points to the broader criminalization of black life in the early twentieth century, and in particular, to the demonization of black working-class men’s bold expressions of New Negro masculinity. Johnson was simply the most famous member of this emerging black working-class subculture that embraced conspicuous consumption and outspoken bravado. These expressions of New Negro manhood provided black men with a means to publicly recuperate their sense of dignity and to protest their dehumanizing experiences of racial discrimination and economic exploitation. In many respects, it was the hip-hop culture of its day, widely associated with black criminality and black masculine pathology. And, much like hip-hop today, this New Negro subculture was criticized roundly for its lack of respectability, not only by white Americans but also by some members of the black middle-class.

It is hardly surprising that Johnson became a political prisoner of sorts in Jim Crow America. At a moment when black people were supposed to remain meek, subservient, and segregated, Johnson was not only outspoken but he openly publicized his love of ostentatious fashion and fast cars. As sociologist Paul Gilroy has pointed out, Johnson “was among the first African Americans to fall foul of the law for the informal crime of ‘driving while black.’ (Darker than Blue, pp. 35-36). Johnson expressed his masculinity through his command of fast cars, which not surprisingly drew white hostility and police harassment wherever he traveled.

Johnson also tempted fate when he opened his own black and tan club (bars where blacks and whites mingled freely) called Cafe du Champion in Chicago’s notorious Levee district. It closed after just three months thanks to a crackdown on the area. It is important to remember that such crackdowns on interracial vice districts, along with the passage of the Mann Act, effectively criminalized consensual relationships between black men and white women in states where there were no antimiscegenation laws.

Outside the United States, Johnson’s performance of New Negro masculinity appealed to men of color in places as far-flung as South Africa, Australia, and Mexico. Some of his biggest fans were the native African houseboys (domestic servants) and mineworkers who lived in towns and cities across the Rand. He also became a hero to the men of the Color Progressive Association of New South Wales, a political organization composed of African American, West Indian, and Aboriginal men who crossed paths as sailors and stevedores on Sydney’s docks. The U.S. government even had agents following Johnson’s moves in Mexico, for they feared that he would incite a dangerous collaboration between Mexican radicals and African Americans living in the border region.

Given these aspects of Johnson’s legacy, it is rather ironic that two white Republican boxing aficionados, Senator McCain and Representative King, have been at the helm of the pardon campaign since 2009. Although they claim that their actions on behalf of Johnson are not politically motivated, King has stated publicly that a pardon for the wronged black heavyweight would be a “strong symbol of racial and political harmony” (one desperately needed by the GOP at a moment when they are trying to figure out how to bring more people of color into the fold, and especially in the wake of the ridiculously racist pronouncements at the recent CPAC convention).

Of course, the Democrats are by no means innocent in the political jockeying surrounding the campaign to pardon Johnson. How poetic would it be for the first black president of the United States to pardon the first black world heavyweight champion on the 100th anniversary of Johnson’s conviction?

I fear that a posthumous pardon of Johnson, however right and just, would be used by politicians on both sides of the aisle to demonstrate their respective parties’ supposed commitment to improving the lives of people of color, especially poor and working-class people of color. However, such a professed concern simply is not reflected in their legislative records. Standing policies, largely supported by both parties, continue to sanction the violent policing and mass incarceration of black and brown youth, the mass deportation of “illegal aliens,” the drone strikes that wound and kill people of color abroad, the hamstringing of public and private sector unions, and the disinvestment from social services designed to help those in crisis. Interestingly enough, the bipartisan resolution to pardon the black champion was put forth just four days after partisan gridlock put the sequester cuts in motion – government cuts that are hurting the very people (poor and working-class African Americans) who made up Johnson’s largest fan base back in the early 1900s.

For a presidential pardon to be meaningful and transformative, it must be envisioned as a beginning rather than an end – as a way for us to come together and publicly reaffirm our shared commitment to honoring the long history of black America’s freedom struggle and to continue fighting all forms of discrimination. Such a pardon would send a symbolic message to people at home and abroad that the United States remains dedicated to the pursuit of racial justice and equality, and that it embraces the model of democratic free speech and political self-determination that Johnson embodied.

4 Comments