Zero Dark Thirty and the Problem of Pakistan

Zero Dark Thirty has been the subject of heated debate since its early release on Christmas Day last year. A number of reviews have focused especially on the film’s deployment of torture as a plot device, and a few Hollywood stars have even organized an appeal against the film ahead of the upcoming Academy Awards ceremony because of this. I agree with some of the reviews (the best, in my mind, are from Jane Mayer for The New Yorker and Deepa Kumar on the blog Empire Bytes), but I would like also to consider a few other aspects of the film that have not been widely discussed as yet.

The short version? Zero Dark Thirty is a drag. But not for the reasons you’d think.

I am currently teaching a class on Islam and the West (a problematic course title, one which my very sharp students have been analyzing and taking apart since our first meetings in January). For the purpose of such a class, which is intended to engage ideas about Islam that have circulated in the Western world (Europe and the United States, for our purposes) since the Crusades, it seemed the timely release of Zero Dark Thirty would make for a wildly interesting field trip. A sort of reconnaissance mission into the heart of the War on Terror entertainment division, if you will. And while after our group viewing, my students offered many thought-provoking considerations of the relationships between race and representation, “us versus them” dynamics, and how the cultural is very, very political, I came away with a much more immediate, though somewhat shallow, reaction:

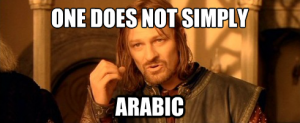

Why is everyone in Pakistan speaking standard Arabic?

The character Hakim (portrayed by Assyrian-Swedish actor Fares Fares), a translator and native informant who is apparently involved with the CIA as well as the Navy Seals, seems to always address the generically threatening brown men who approach our lily-white (anti)heroine (her name is Maya, played by Jessica Chastain) in Arabic. Throughout the entire film. Sometimes there is Urdu. I heard Farsi and Pashto once or twice as well. But Arabic seems to be the language of Pakistan in Katherine Bigelow’s version of events. Sometimes, in real life, it is. Arabic and Urdu share an alphabet. They are linguistically related. But they are not mutually intelligible, and standard Arabic (which is not the same as Classical Arabic, the language of the Quran) is not even intelligible in most of the Arabic-speaking world. So. Standard Arabic in Pakistan. Yalla, let’s discuss.

I understand, in a way. Pakistan is full of brown people and Muslims. Or, brown people are all Muslims. Terrorists are all Muslims. Muslims are Arabs and brown. Terrorists, and therefore Muslims (and therefore brown people), speak Arabic. I’m not entirely sure how to chart this, but Brown People, Muslims, Terrorists, and Pakistan exist in an ever-shifting constellation. At least, they do in Zero Dark Thirty.

But when Pakistanis don’t speak Arabic… they only understand English! Towards the end of the film, when our brave American soldiers (who all seem to have beards, but do not seem to be jihadi terrorists – very confusing) are moving throughout the compound of the man who has been harbouring Osama bin Laden (“UBL” in the film’s parlance), Hakim stands outside warning the muttering horde of Abbottabadians who have been awoken by the sounds of extra-legal assassinations to go home. (Nothing to see here, folks, move it along.) Hakim initially begins warning the horde in Urdu (there’s really no other way to put it – we don’t have people so much as hordes in the film). It may have been Hindko, the most commonly used language in the city (and one that I myself am not familiar enough with to discern). Regardless, despite American soldiers pointing guns at them, the Pakistanis draw nearer. No common sense, these brown people. Hakim then implores them in English: “They will kill you! Go home! They will kill you!” Only then does the horde stop.

Yes, thank you Hakim. I am sure that our friends from Abbottabad would never have the sense to stay away from the armed soldiers had you not let them know in English.

But that is precisely the dilemma presented by the film’s fast-and-loose treatment of Pakistan (and brown people). The portrayal of black sites (filmed in a currently active prison in Jordan – something that made Jessica Chastain very sad), of Pakistan, of a nightclub in Kuwait; these portraits of lands teeming with brown people – every one of whom may be a terrorist – this is the problem with the film. The torture scenes, though never depicting the hundreds of detainees who are completely innocent of any wrong-doing, are not precisely why I didn’t like this film. I actually found the torture scenes rather ambiguous, though I don’t believe that a majority of the American audiences care either way. In my mind, the torture in the film, and the positions of the torturers, are not as clearly pro-torture as some previous reviewers have argued. What is clearly pro-torture is that the torture always seems to work. But this is not what I am concerned with in this post (others have covered this topic quite well).

Rather, I dislike this film because it is, first and foremost, monstrously boring. Long and poorly paced and not even well written, at that. I dislike this film because I hate when (white) women are propped up as heroes in some post-feminist militarized fantasy (the hunt for Osama bin Laden is Maya’s “baby” and she cries when the mission is through – a septic analogy for motherhood). I dislike this film because its racism and Islamophobia is not in the depiction of torture, is not through positioning a white CIA official as a Muslim (shocking!), is not even in the casual slights and slurs used against the (always guilty) detainees, the food, or the people (“it’s not safe being white here”). Its inherent racism and Islamophobia is instead tucked away within the casual Orientalist inclusion of Arabic by Katheryn Bigelow and Mark Boal. Arabic is the film’s aural cue to the audience: they have spoken Arabic! Begin racializing The Browns!

We don’t need the browns to have bombs strapped to their chest (though one does, in the film). We don’t need the browns to wear kufis or galabeyas or burqas (though some do, even though burqas are particularly out of place in most urban areas in South Asia – the equivalent of seeing a dozen women in burqas at a strip club in East Lansing). We don’t even need the browns to be incompetent terrorists, oil-rich sheiks, or leering at scantily clad Western women (though, again, ZDT features elements of all of these stereotypes). As long as the browns we identify as bad share a common language – Arabic – we can safely cheer against them. Do I think most audiences understood that Arabic was being used in the film? Not at all. But I do know that Arab = Muslim = terrorist is the maths for far too many. So that the browns all seemed to be able to communicate with each other (regardless of where they are situated or said to have come from) is the fear mongering take-away from the film. It’s why I don’t speak Arabic on the phone while I’m at an airport. It’s why too many of my friends and family have been treated with suspicion while out in public. “If it sounds like an Arab, looks like an Arab” and so on.

Zero Dark Thirty consciously avoided many of the common stereotypes we’re always on the watch for. We have a white Muslim who works for the CIA and approves of torture. We have a brown translator in the CIA and the Navy Seals who seems torn about the tasks he must perform in the War on Terror. We even have a lead – Maya – who seems impressively knowledgeable about Islam, and sometimes even discerning of the differences between radical ideologies and commonly held religious tenets. But the casual, almost off-hand presence of Arabic in the everyday lives of Pakistanis reduces them to nothing more than brown bodies in a desert. Much as they appear, I imagine, on an unmanned aerial drone operator’s control screen. This reductionism, the relegation of Pakistanis themselves to the background of the film, is the true danger of this film. I think I’ll cheer on Emad Burnat’s Five Broken Cameras instead this Oscars season.

28 Comments