What Does Democracy Look Like?

I’m feeling very ambivalent about voting and electoral politics more generally these days. Perhaps it has something to do with the fact that I’m ineligible to vote in the United States and I’m also ineligible to vote in my home country of Canada. In effect, my itinerant life has left me disfranchised both where I live and where I grew up. Of course, my disfranchisement is much more a sign of my own privilege than marginalization: my ability to move to another country to study for a PhD and to work in a middle-class profession abroad.

There are far more sinister and sweeping forms of disfranchisement at work in the United States today, including the stripping of voting rights from those with felony convictions and from those without “proper” identification under the new voter registration laws. According to The Sentencing Project:

Nationally, an estimated 5.85 million Americans are denied the right to vote because of laws that prohibit voting by people with felony convictions. Felony disenfranchisement is an obstacle to participation in democratic life which is exacerbated by racial disparities in the criminal justice system, resulting in 1 of every 13 African Americans unable to vote.

Although the voter ID laws have been pitched as a means to minimize “voter fraud,” they will have a disproportionate impact on the poor, African Americans, the elderly, students and people with disabilities. This is not what democracy looks like.

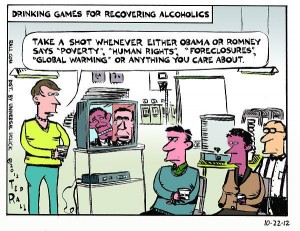

So, why vote at all? Although this question seems to be an anathema to all good liberals, I’ve heard this question from students, from friends in the social media sphere, and from the numerous people I’ve spoken to throughout my travels promoting my new book. I’ve thought long and hard about this question. After all, despite the mind-numbing hours upon hours of discussions, debates, and analyses in the lead-up to this year’s election, our two main candidates have, for the most part, failed to address some of the biggest bread-and-butter issues facing a growing proportion of the U.S. population (particularly people of color and their children) struggling under the weight of foreclosures, joblessness, underemployment and the attack on unions, food insecurity and the inaccessibility of healthy choices, the underinvestment in truly public education, poor quality health care and a lack of affordable health insurance for all, poverty and destitution, homelessness, mass incarceration, police brutality, the stripping of reproductive rights, the lack of sensible and humane immigration policies, and the list goes on. (And on the foreign policy front, the United States’ continued military interventions and neoliberal bullying abroad and their real human costs.) Seriously now, enough of the fake pandering to the “middle class”! To me, it makes perfect sense why so many Americans are not so hot to race to the polls on Election Day.

I’ve had to stop watching the presidential debates because they tend to raise my blood pressure without providing me with any new information. I started to feel as if the debates (and the presidential campaigns more generally) were an elaborate and over-produced exercise in “wag the dog.” They have become what I call “People Magazine-ified,” more tabloid than actual news. Campaigning has become an industry unto itself, as candidates sell themselves to voter-consumers and campaign managers rely on sophisticated polling data akin to market research. We are being encouraged to fight over which party’s (and their well-heeled backers’) scraps we would prefer to catch, while inequality on a number of fronts continues to deepen. This might seem like hyperbole to some, but I can’t shake the feeling that we are losing sight of the larger picture in focusing on things as mundane as the candidates’ body language and “likeability.”

That said, I do think that the practice of voting still matters, even in the United States’ two-party system complete with an ossified Electoral College. If it didn’t matter then there would not be such a concerted effort (particularly on the Right) to keep certain people from voting. However, at a time when many view voting as a form of consumption – as an end in itself – we seem to have forgotten what role voting actually plays in our political system.

We only need to look back to the days when black Americans in the South were fighting for the basic right to vote to see that we need to foster and participate in political action that takes place outside the narrow forum of electoral politics. The likes of Septima Clark, Ella Baker, and Fannie Lou Hamer (and so many others) always understood that voting was just one strategy of many. Voting was just the beginning. They worked to cultivate grassroots leaders to collectively push for change in their communities from the bottom up. They knew that politicians would only do what their constituents forced them to do. They had to come up with their own visions of what freedom and equality meant to them. They had to advance their own ideas of what kind of world they would like to create because no political party factored them into its platform. They organized citizenship schools, took to the streets, led sit-ins and other direct-action campaigns, supported workers’ rights, created farming cooperatives, etc., in order to make their own change. Now at a moment when big-money interests have grabbed control of electoral politics in the United States, these earlier models have renewed applicability. We are not powerless. Clark, Baker, Hamer, and other visionary black women have already shown us what democracy looks like.

8 Comments