Occupying Myself: Resisting the Colonial Voices Within and Accepting My Heaviness

By Erin “Mari” Morales-Williams

Right now I am depressed. My aunt’s husband sexually violated me when I was a teenager, and since she is still with him and he still comes to family events, I am forced to mentally split if I am to still enjoy my family.

Right now I am depressed. My aunt’s husband sexually violated me when I was a teenager, and since she is still with him and he still comes to family events, I am forced to mentally split if I am to still enjoy my family.

He was in my house for the past three days for my cousin’s graduation festivities, and though I have healed and forgiven, his presence is still painful for me, almost as painful as how accommodating my family has been. It is because of experiences like that, that my doctoral research is on race, gender, sexuality and power. Although I have intellectualized sexual trauma and recovery in many papers in graduate school, the pain is still real, and I still hurt. Naturally, now is the best time for me to write and reflect on being a doctoral student and mental heath. I can become overly intentional in how my writing serves the healing paths of my readers. I tend to write for them instead of writing for myself. I have learned that removing my existence from how I serve the world is a learned fallacy of patriarchy. How could I help other women heal themselves if I didn’t realize my own healing? So it is good that I write in this heaviness. This way I am not allowed to share a reflection that is padded by any half-lived sermon, or pressured to offer some self convinced happiness. This moment is perfect. I am sick, runny nose and all, and I must write now because writing for myself has always brought relief. That kind of writing has always saved the day.

I started my Urban Education doctoral program at Temple University in Fall of 2007. At the time, I was a feisty 21-year old, and initially I wanted to start a school because I wanted to create radical change for our urban children of color. Disappointed with my own Eurocentric-schooling experiences, and frustrated with the academic spaces I had taught in, I wanted to develop a school that was community based, culturally relevant, and spirited by the aims of social justice. I had hoped that entering the academy would give me academic license to create more liberatory spaces of learning for our urban communities.

But graduate school, like all of my other schools, was a colonial experience, and I realized in graduate school how colonized I still was. I still believed that those who dominated conversation were the smartest, that my intelligence was validated by my professor’s compliments; that if I couldn’t bring something new to the conversation or anything at all, that I might as well not be there. As an intellectually gifted colored girl, most of the White privatized institutions I attended held me to high expectations and offered little to no positive reinforcement. Receiving less love and attention than my white counterparts, my academic accomplishments never felt enough. They felt like nothing because I never heard that they meant something and it said something amazing about me. Aided by the hyper-critical voices I had internalized, the silences and aloofness of my colonial teachers actively affirmed my own self-hatred. And while I did have a few supportive White teachers, I had no White mentors that supported me from a deeper and more radical place of love and understanding. Perhaps it was their own need to be color blind that blinded them to the particular needs I had as a smart and colored child.

The colonial experience, if not resisted, will always make one feel as if we are not enough; it will always push us to the margins until we can’t breathe, or read or write or create, or feel entitled to the right to be wrong. Living that kind of half-life for weeks in my first semester, and then getting into a major car accident on the highway, eventually led to my anxiety attack in my Urban Schools class. I thought I felt a blood clot explode and that I was bleeding out. When the ambulance brought me to triage, the Asian nurse listened to me explain the pop-sensation I felt as my peers discussed urban school reform. She nodded as she scribbled on her clipboard and finally said, “You don’t have blood clot, you just need doctor for the head, you just like, a little crazy.” I sat in the wheelchair in the waiting room, and then waited for the death I knew was coming, the death I had secretly prayed for so many times before.

When I was 12 years old I wrote a will and note to my beloved mother. I was praying that I could bypass the theater of suicide and just magically die. Sleep my way into death; be accidently pushed off the platform at 125th. I didn’t know that I was deeply repressing sexual and emotional trauma from my family and school, so I often felt I didn’t have any good reason to be that sad. I heard voices that were ugly and poisonous, mocking voices that disciplined with hate and with haste. They spoke with the intensity of a mother’s voice, so I quickly listened and accepted their dark syllogisms.

You are dumb and stupid which is why Louis got a 100 and you didn’t!

You are wasting people’s time, you shouldn’t be here!

You are nothing. You are nobody. I hate you.

I sorrowfully bowed to their rage, made concessions to doing better, feeling little comfort when I did; always knowing the voices would come back, that they always had something to say, over and over again. If I didn’t feel punished enough by the voices, I would hit myself until my cheeks became numb, or until a voice said that I was too weak to make the necessary bruises. Then I’d cry myself to sleep, praying a prayer to never wake up. And though I did plenty of laughing and dancing, prayers for death happened for years. When I felt alive as girl, I transformed into the most energetic camp counselor that inspired my girls to win kickball games against rude boys; I danced with scared girlfriends between old train cars that speed through the underworld of New York City. I won swimming meets at Kips Bay Boys and Girls Club, snapped back at crude dudes with nothing to lose, stood up and fought against White teachers undeveloping our Black children in Philly. When I felt alive, I felt unafraid to be awake, confident that the voices had retreated to their corners and been somewhat satisfied into silence. There were many days that were good and hopeful, despite all that I kept so carefully hidden.

That is what mental illness can look like. That is how school can operate as a colonizing force. Those were colonial voices I heard.

Decolonization of self has been the moment-to-moment work of Occupying Myself, through therapy, yoga, Ochun, activism, and radical, radical writing. I recognize that the academy was never set up for my survival, especially not if I intend to live freely and honestly, as a urban Black Puerto Rican feminist queer rape survivor warrior poet dancer activist. And because I am a spiritual daughter of Audre Lorde, I don’t think we can use the “master’s tools to dismantle the masters house.” My fierce intention for healing, for self-occupation and self-actualization forced me to find an Underground Railroad in this ivory tower, even if it meant giving up the luxuries of an A, or a professor’s satisfaction, or a well-padded CV. This desire for healing was conjured by the self-love I was allowing to be privileged, one encouraged by so much of the woman of color feminism I was reading. Audre Lorde, bell hooks, Gloria Anzaldua, Patricia Hill Collins were begging me to put myself first, to trust in the Universe, and believe in the power of our freedom fighting ancestors.

It was many things that called me to self-occupation, even when healing seemed so far away.

It was reading and teaching Paulo Freire as Marc Lamont Hill’s teaching assistant, dedicating vast amounts of time and energy into transforming my classroom into a safe and radical space. It was not just having a conversation about the moral triumph of Brown V. Board, but what it meant that we had that conversation in a racially homogenous classroom. It wasn’t just discussing Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, but literally walking out of our cave of a classroom and looking at the sun until our eyes burned. It was assuring them that that was the beauty and pain of truth. It was all the students who then came to office hours to talk about depression and hopelessness, faith and acceptance, resistance and possibility.

It was Dr. Billie Gastic telling me that finishing this program was not about how smart I am, but how resilient I am.

It was hearing a graduate student say, “Research is me-search.”

It was being raped by a friend that I had been intimate with; the gnawing process of letting go a seed that I couldn’t allow to sprout from my karmic debt and live in bitter shame.

It was writing my papers on abortion, and sexuality; starting the Yoni Project, a sexually healing and sexual empowering workshop for young girls and women, and writing a paper about it.

It was finding out that my boy Abim had committed suicide, all the visions I was receiving of his last moments and last thoughts.

It was the wail of his father, a sound that will always bring me to a quiet numbness. It was writing about mental health.

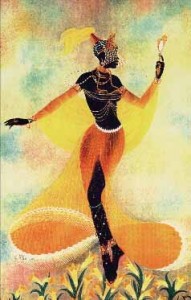

It was finding Ochun[1], dancing, offering honey to her rivers. And of course, writing a paper about her too.

It was learning that my heaviness, the one that comes from living deeply and widely, grounds me, just as my inner light strengthens me, pushing me to transcend into higher grounds that must also be transcended toward even higher ground. That life was an upward spiral. Some days I’m at the top; other days, like today, I’m at the bottom. My movement upward depends on how accepting of myself I can be at the bottom. I need it, so I respect it. I am beginning to believe we all should. No matter which colonial house we live in.

Notes

[1] Ochun is a deity that is widely revered in the Santeria and Lucumi religions of Africa and the African Diaspora. She is praised for her healing powers of the body, particularly for sexual trauma.

___________________________________________________

Born in East Harlem and raised in the Bronx, Mari is a doctoral candidate at Temple University who is invested in scholar-activism. She is currently writing her dissertation, “ ‘Love in a Hopeless Place’: Young Urban Women of Color as Public Pedagogues and their Lessons on Race, Gender, and Sexuality.” Her research and activism are motivated by her fire as a Black-Puerto Rican feminist queer rape survivor, prison abolitionist, and community-based educator and healer. She dreams of one day opening up an art activist healing sanctuary for urban youth.

Born in East Harlem and raised in the Bronx, Mari is a doctoral candidate at Temple University who is invested in scholar-activism. She is currently writing her dissertation, “ ‘Love in a Hopeless Place’: Young Urban Women of Color as Public Pedagogues and their Lessons on Race, Gender, and Sexuality.” Her research and activism are motivated by her fire as a Black-Puerto Rican feminist queer rape survivor, prison abolitionist, and community-based educator and healer. She dreams of one day opening up an art activist healing sanctuary for urban youth.

76 Comments