The Invisible War: A Film on Rape, Women and Combat (A Review)

Horrifying . . . devastating . . . infuriating . . . saddening. These are the emotions I felt as I watched The Invisible War, a new film, written and directed by Kirby Dick, which opened nationally yesterday. To be sure, The Invisible War isn’t your typical war story. It’s a gripping docu-film that focuses on the “powerfully emotional stories of rape victims” within the U.S. military, and their “struggles to rebuild their lives and fight for justice.” Shining a spotlight on a world largely defined by masculinity, combat, force, sex, and concealment, this film unveils the following:

Horrifying . . . devastating . . . infuriating . . . saddening. These are the emotions I felt as I watched The Invisible War, a new film, written and directed by Kirby Dick, which opened nationally yesterday. To be sure, The Invisible War isn’t your typical war story. It’s a gripping docu-film that focuses on the “powerfully emotional stories of rape victims” within the U.S. military, and their “struggles to rebuild their lives and fight for justice.” Shining a spotlight on a world largely defined by masculinity, combat, force, sex, and concealment, this film unveils the following:

- 20% of women are assaulted while in the military

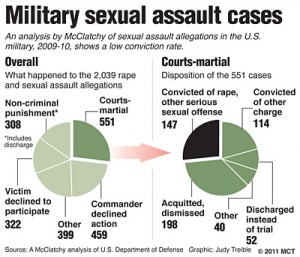

- Only 8% of the assailants are prosecuted, with only 2% facing conviction

- 80% of the victims do not report

- 25% of women do not report rape because the person responsible for receiving the report is oft times also the rapist

- 1% of men in the military, totaling 20,000, are victims of rape

- 15% of incoming military recruits acknowledge that they have attempted or committed a rape prior to entering the service

- 40% of homeless female veterans are victims of rape

- Of the 3,223 cases that are actually prosecuted, only 175 of the assailants would serve jail time (all numbers are from the film or related press)

- “The Veterans Administration spends approximately $10,880 on healthcare costs per military sexual assault survivor. Adjusting for inflation, this means that in 2011 alone, the VA spent almost $900 million on sexual assault‐related healthcare expenditures” (press packet).

The Invisible War paints a picture of injustice and sexism, and a culture of sexual violence that has reached epidemic proportions. However, it does more than offer disheartening and infuriating statistics. It provides a story, a story about women and men—those who are celebrated as heroes, who receive standing ovations at parades, whose service is lionized and celebrated over and over again—who have been raped while serving in the U.S. military. Irrespective of yellow ribbons and holidays, it is a story that illuminates rape culture and the ways that victims are multiply victimized within a culture of warfare, camouflage (or cover-up), and sexual violence.

The filmmakers interview roughly 70 survivors of military rape, women and men, who in the face of victimization by their assailants, their military community, and countless others, have decided to fight back. We learn the stories of women like Kori Cioca who was raped and physically beaten while serving in the U.S. Coast Guard. We hear how her assailant, who was also her commanding officer, didn’t just rape her, but also broke her jaw during the attack. And, we learn how Cioca was reminded (over and over again) that her punishment for “lying” would be a court-martial, when attempting to report the assault to those in command.

The Invisible War elucidates a culture of rape and victimization as well as the continual cultivation of revictimization, wherein the military instigates an “in-house” society of violence—among comrades. Some victims were even charged with adultery due to the assailant being married! Moreover, of the five women from Marine Barracks Washington interviewed in the film, four were investigated and punished after reporting incidences of rape. They were told to “suck it up,” unfairly disciplined professionally, threatened with prosecution, and demonized publicly. And perhaps worse of all, they were often forced to face their assailants every step of the way.

The Invisible War elucidates a culture of rape and victimization as well as the continual cultivation of revictimization, wherein the military instigates an “in-house” society of violence—among comrades. Some victims were even charged with adultery due to the assailant being married! Moreover, of the five women from Marine Barracks Washington interviewed in the film, four were investigated and punished after reporting incidences of rape. They were told to “suck it up,” unfairly disciplined professionally, threatened with prosecution, and demonized publicly. And perhaps worse of all, they were often forced to face their assailants every step of the way.

From suicide attempts to physical pain, the film documents several consequences of rape, to include but not limited to rising costs, exacerbated by an “in-house” rape culture. We see this with Cioca. The physical pain resulting from her assault is endless. Because of her broken jaw, Cioca continues to live on a liquid diet, she cannot go outside when it is cold because of pain, and probably most dispiriting, Cioca’s assault remains with her both physically and emotionally. In fact, she often wakes up screaming. The dual agony of severe discomfort and traumatic recollection are unceasing. Unfortunately, this reality has been largely ignored by the VA, which refused to cover all of her medical expenses.

The power of The Invisible War rests with the elevation of the voices and experiences of the soldiers themselves and their families. The consequences of sexual violence can be felt in the physical and emotional anguish expressed throughout the production. However, though the film gives voice to victims of rape (and their families) within the military, therefore breaking the silence perpetuated by a complicit media, it misses a critical opportunity to expand the discussion to explore the effects and entwinement of militarism, patriarchy and misogyny in our broader socio-political context. At times, The Invisible War seems to even downplay how patriarchy and American institutions/ideology(ies) actually sanction and give life to rape culture(s). In short, in trying to spotlight the injustice facing men and women in the military, and the systematic camouflaging (pun intended) at each level in the chain of command, The Invisible War misses the opportunity to make some pretty significant connections.

A more efficient grasping of sexual violence within the military requires looking at its deployment of gendered language as well as the ways in which women are objectified within and without military culture. It also demands that we look at “base women,” the relationship between U.S. operations overseas and prostitution, as well as the ways that sexism infects U.S. policies. In addition, a more critical reading of sexual violence pushes us to explore the treatment of women within the U.S. military, particularly those serving in countries currently occupied by the U.S.

Feminist theorist Cynthia Enloe, in her essay, “Wielding Masculinity inside Abu Ghraib: Making Feminist Sense of an American Military Scandal,” identifies misogyny and sexism as core values of militarism, thus pushing readers to think about their manifestation(s) both inside the U.S. military and without.

It is not as if the potency of ideas about masculinity and femininity had been totally absent from the U.S. military’s thinking. Between 1991 and 2004, there had been a string of military scandals that had compelled even those American senior officials who preferred to look the other way to face sexism straight on. The first stemmed from the September 1991, gathering of American navy aircraft carrier pilots at a Hilton hotel in Las Vegas. Male pilots (all officers), fresh from their victory in the first Gulf War, lined a hotel corridor and physically assaulted every woman who stepped off the elevator. They made the “mistake” of assaulting a woman navy helicopter pilot who was serving as an aide to an admiral. Within months members of Congress and the media were telling the public about “Tailhook” – why it happened and who tried to cover it up (Office of the Inspector General, 2003). Close on the heels of the Navy’s “Tailhook” scandal came the Army’s Aberdeen training base sexual harassment scandal, followed by other revelations of military gay bashing, sexual harassment and rapes by American male military personnel of their American female colleagues (Enloe, 1993; Enloe, 2000).

Enloe makes it clear that sexism, sexual violence, and misogyny are central components to militarism, thus representing the ideological foundation of a militarized culture that is consequentially exhaustively threatening to women and non-gender-conforming others. She highlights the level of violence in elucidating levels of sexual violence and misogyny surrounding U.S. bases:

Then in September 1995, the rape of a local school-girl by two American male marines and a sailor in Okinawa sparked public demonstrations, new Okinawan women’s organizing and more U.S. Congressional investigations. At the start of the twenty-first century American media began to notice the patterns of international trafficking in Eastern European and Filipina women around American bases in South Korea, prompting official embarrassment in Washington (an embarrassment which had not been demonstrated earlier when American base commanders turned a classic “blind eye” toward a prostitution industry financed by their own male soldiers because it employed “just” local South Korean women). And in 2003, three new American military sexism scandals caught Washington policy-makers’ attention: four American male soldiers returning from combat missions in Afghanistan murdered their female partners at Fort Bragg, North Carolina; a pattern of sexual harassment and rape by male cadets of female cadets – and superiors’ refusal to treat these acts seriously – was revealed at the U.S. Air Force Academy; and testimonies by at least sixty American women soldiers returning from tours of duty in Kuwait and Iraq described how they had been sexually assaulted by their male colleagues there – with, once again, senior officers choosing inaction, advising the American women soldiers to “get over it”(Jargon, 2003; Lutz and Elliston, 2004; The Miles Foundation, 2004; Moffeit and Herder, 2004).

All of this highlights the fact that it’s about time we move the conversation beyond the military itself (while of course maintaing our criticisms), and critically examine the myriad ways that sexual violence manifests itself in barracks, and in countless communities. This points to another shortcoming of the film: its privileging of whiteness. While illustrating the fact that sexual violence impacts women across communities, the film ultimately calls attention to the injustices faced by white women. It would have served the filmmakers well to give voice to the devastating circumstances surrounding the rape and death of LaVena Johnson (and others) whose death was officially ruled a suicide despite these facts:

The 5-foot tall, 100-pound woman had been struck in the face with a blunt instrument, probably a weapon. Her nose had been broken, and her teeth knocked back. There were bruises, teeth marks and scratches on the upper part of her body. Her back and right hand had been doused with a flammable liquid and set on fire. Her genital area was bruised and lacerated, and lye had been poured into her vagina. The debris found on her suggested her body had been dragged. And despite all this mutilation, she was fully clothed when her body was found in the tent, with a blood trail leading to the tent.

As with many of the cases documented within The Invisible War, the Army refused to investigate, thus stonewalling attempts to secure justice. Had The Invisible War engaged the experiences of women and men of color in the military, and the consequences of sexual violence when race and racism are involved, and had it looked at incidences of rape involving South Korean and Japanese women, its efforts to both summon and spotlight this horrific epidemic would have been much stronger, at minimum pioneering a cinematic discourse around the intersections of race, gender, sexuality, and nation.

Yet, The Invisible War does something very significant: it get’s us talking, thus (hopefully) influencing multiple conversations about the injurious intersections and force of sexual violence, sexism, patriarchy, militarism, racism, classism, homophobia, and misogyny within and outside of U.S. military culture. If nothing else, The Invisible War shows us that the very oxygen that allows for sexual violence to breathe, and society to turn a blind eye…is also wrapped up in those yellow ribbons, each of which must be untied immediately…at minimum to allow us to hear all the tongues violently struggling to speak their own truths, and to see the mountains of pain and injustice starring us right in the face…

12 Comments