Race, Mad Men, and Nostalgia

By Claire Oberon Garcia

Like three million other Americans, I eagerly looked forward to the return of Mad Men. I love the show. But as an African American woman born in 1956 who did most of her growing up in the Northeast corridor between Washington, D.C., New York City, and Cambridge, Massachusetts, the appeal of the show goes beyond seeing familiar packaging of items I grew up with, memories of my parents’ daily martinis at the end of the day, and color schemes of the era that now hold an emotional resonance. Of all the pleasures the show has to offer me, nostalgia is not one of them.

Rather, the appeal lies in something more painful yet fascinating, something akin to Ralph Ellison’s appreciation of how the blues can “finger the jagged grain.” Unlike the nostalgia of the wildly popular novel and film versions of The Help, in which a simpler racial past (racism is a matter of individual meanness overcome by individual niceness) comforts a troubled and complicated present (we live in an age of both Michelle Obama and the appeal of Minnie and Aibleen), the award-winning television show reminds me of the discomforts of growing up in the vanishing world of the black bourgeoisie, of questions and resistances that I had no words to articulate, and of the sense of being an expatriate without a patria that is central to my identity, even living almost all my life in my own country.

Like many black bourgeois girls of my era, who lived either in the South, like Condoleezza Rice, or in the North, like former Washington Post writer Jill Nelson, my sisters and I grew up in a world that seems, in hindsight, almost unbelievably insular. Television channels were not as numerous, and mass media voices were not as ubiquitous as they are now. We turned on our single small black-and-white television set for The Ed Sullivan Show, The Man from UNCLE, and whatever program had a black guest on it that week (usually Leslie Uggams, Sammy Davis, Jr., Eartha Kitt, or Julian Bond.) The main connection between the outside world and our large, brick colonial house on Kalmia Road, in the heart of what more than forty years later I learned had a name—the “Gold Coast”—was provided by books and excursions with my artist mother to the National Gallery and the Corcoran.

Alongside the Nancy Drew and Edgar Eager series, Walter de la Mare’s poetry anthologies, and 19th century British novels on our bookshelves were biographies of George Washington Carver and Phillis Wheatley. When, in fifth grade, our class made the traditional overnight excursion to a Williamsburg that contained no sign of slave lives and I brought home a book about Patsy Jefferson that featured the little blonde girl with a fat Mammy smiling behind her on the cover, my mother threw it away before I had a chance to read it. When a white woman offered a friend and me the opportunity to clean her apartment for what seemed a princely sum, my mother hit the roof—as much for my working for an hour as a maid as for going into a stranger’s home. Our own maid and gardener were always referred respectfully to as “Mrs. DuBois” and “Mr. Ward”—never by their first names, and never as “the help,” even when talked about in the third person.

My sisters and I wore tights and jumpers and hot-combed hair constantly controlled with oil, headbands, and barrettes. Sometimes we put the tights on our heads and pretended that they were long braids that we could flip over our shoulders. We were proud to be Negro, but also proud to be people with “taste.” My mother’s strongest pejorative term was “a Stepin Fetchit” (as in, “he’s acting like…”), the second strongest was “vulgar.” The only music we heard in our home in the early years was classical, jazz, Odetta, and Pete Seeger records.

We lived in a world that wasn’t represented anywhere: not in the few hours of television we saw, the three daily newspapers we read (morning and evening Washington papers and the New York Times), the many magazines around the house, the few movies we did see, or even in our constant reading. Our world was not the world of the fearless slave running for freedom, nor that of the brave well-dressed Negroes in that scary place my parents referred to as “below the Mason-Dixon line.” Our neighborhood of spacious traditional houses was peopled by black judges, dentists, and doctors, who lowered their voices when, during a discussion of “the way things were,” a child was in hearing. We certainly never saw ourselves in any advertising, save for in Jet and The Crisis.

My mother gave dinner parties that started with cocktails and featured “veal birds” from a recipe in the New York Times. The guests were always African American professors, artists, and people involved in Civil Rights organizations; newly decolonized citizens from Asian and African countries. The only white people I remember were Jewish people in same professional categories as the African American guests, and a few Europeans. Strictly forbidden from coming downstairs after being introduced, my sisters and I watched, from between the landing rails, the women in saris or sheath dresses and men in bright traditional dress or suits and ties. Every summer we spent a month in Martha’s Vineyard or Cape Cod, renting from other black families whose salaries or generations of family wealth were greater than our parents’. The adult world that we watched from an appropriate distance was never depicted on television or in the movie theatres.

We lived in a parallel world to the world of Mad Men, though that white supremacist, patriarchal world shaped ours in both visible and invisible ways, and Mad Men nevertheless had a role in shaping our desires. At a certain age, my sisters and I started saving our money for Yardley lip gloss (“Slicker over, Slicker under, or Slicker alone”) and begging for shocking pink go-go boots from Thom McCann, and a blonde, flat-bottomed model named Andrea Drom was an image of beauty. Although our world was not really disconnected and safe from the “prejudice” and racial violence then, it felt relatively uninfiltrated by mass media nevertheless. Our home world seemed infinite, thanks to how our mother encouraged our imagination and creativity. We would dance out whole stories to a recording of Aaron Copeland’s Appalachian Spring, having no idea that Martha Graham had beaten us to the punch. We put on a full-length production of Swan Lake (though our mother stopped us from charging our neighbors to see it), not knowing that ballerinas were never black. My sisters and I stayed up until dawn on summer nights, crammed into the only air-conditioned room aside from my parents’ bedroom, making up stories.

We knew that we would never look like the flat-haired blondes in the Yardley commercials. We watched the loud, gum-cracking black girls on the bus and knew that we would never be like them, either. We were proud to be Negro, and racists who thought that we were not as smart and pretty as white girls were clearly “ignorant.” But there were disturbances and questions that I couldn’t articulate, and of course these came to a head with adolescence and my mother’s death. At school I was impatient with the “project kids” who didn’t know how to read and held up the class when it was their turn to answer a question, yet I felt an angry despair and identification when I saw them begging at the doors of the Arena Stage on weekend nights.

In 1968, when I entered the National Cathedral School for seventh grade, it was like entering a mirror world separated from my own by hard, cold, impenetrable glass. The girls in Mrs. Williamson’s 7A seemed to share many of my own girlhood experiences: Nancy Drew and Jane Eyre, ballet lessons, selling Girl Scout cookies, and summers in New England where colonies of women and children were visited each weekend by husbands and fathers still toiling in the cities. But I was different, and my realities did not exist in theirs, as I found out when a classmate’s mother welcomed my spending the night at their house, but wouldn’t allow her daughter to spend the night in “a black neighborhood” that she didn’t realize was actually “nicer” than her own. Despite being part of a sprinkling of dark girls who had been integrating the expensive girls’ school for the past four or five years, and the fact that the senior class president was a beautiful, chocolate-skinned young woman with an Afro, I was perceived as a strange being.

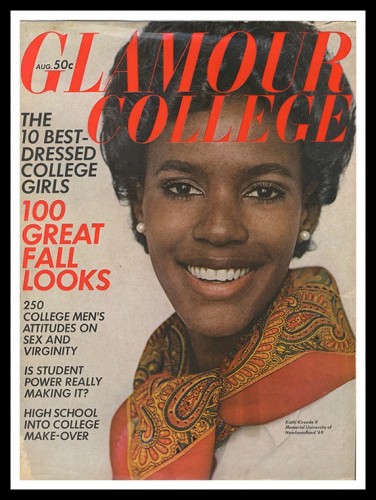

But I knew that there was something wrong with that world, not with me. That spring, Martin Luther King had been murdered and rioters had destroyed my father’s green Jaguar sedan a few blocks north of our house. I started seeing women with glorious hair that resembled my previously troublesome “new growth” and I “went natural.” And we started seeing black people on television and in the newspapers, not just when they were demanding things, but modeling sheath dresses and serving Campbell’s soup to their smiling families. In the summer of 1968, on a weekend visit to our cottage on Cape Cod, my father brought home my first issue of GLAMOUR magazine because it had a black model on the cover—something he had never seen before in his 40-something years. Suddenly, there was a way to question the world that the Mad Men had made, the world that white and powerful men had wanted us to believe was real, the world in which anyone who was not a white and powerful man played a purely supporting and often invisible role. Black people, young people, women, and poor people were challenging the status quo these men had created and profited from. In the spring of 1969, my mother died. That same year, I discovered Georgetown hippie shops, natural hair, and “the revolution.”

The first episode of the return season of Mad Men is framed by black people: first, dignified and noble families picketing a rival ad agency for access to jobs and then at the close, dignified and noble people bearing resumés and hope in Sterling and Cooper’s joking but public declaration that it was an “Equal Opportunity Employer”. Previously on Mad Men, the black presence consisted of the elevator operator, a bohemian black girlfriend of one of the ad men who never got written into the plot, and a Mammy-style maid who tried not to let her interest in the Civil Rights movement interfere with her providing some emotional sustenance to the emotionally deprived Draper children. She, too, was written out of the plot pretty quickly. The storyline of Mad Men has no place for fully developed, interesting black people, just as popular culture in the United States, until the mid-sixties, could only recognize black people as “the help.”

So what is the appeal of Mad Men for me? Of course, it is superbly written and acted, and has a cast of complex and intelligent characters in interesting relationships. Now that the Downtown Abbey season is over, it is the perfect Sunday night escapist television fare for progressives who would never want to live in the worlds these programs portray. For me, watching Mad Men prompts an aesthetic pleasure but also a fructifying pain, as it reminds me that, as a black woman, the “bad old days” and the “bad guys” who made them up and enforced my invisibility are still around and powerful. Madison Avenue, together with Hollywood, strictly polices the parameters of black life in the mainstream media and the popular imagination. And in the years that we have had an intelligent, self-made dark-skinned woman in the White House, America has fallen in love with a pair of maids who remind their white charges in a black-face attempt to capture black folk voices that, “You is kind. You is smart. You is beautiful,” and who “just loves [them] some fried chicken.” American readers and viewers have made the white creator of these maids a millionaire.

Watching Mad Men sharpens my alertness: it reminds me of the pressures that shaped the seemingly insular and fragile safety of the world of my childhood, for better and worse. It reminds me of the tenacity and vision of my parents, who tried to arm their daughters with what they thought were the best weapons with which to confront and participate in American society in the mid-twentieth century, a society that a generation later still recognizes black women only in the roles of nurturing mammies, lascivious Jezebels, or loud and angry Sapphires: an excellent education, a love for reading and travel, “good taste”, and the freedom of self-recognition. Most importantly, my parents gave my sisters and me our almost reflexive questioning of “the ways things are” or “the norm.” While most of my adolescence and young adulthood was spent resenting their early efforts to protect me from the harsher realities of American race relations, I have since discovered that their child-rearing philosophies and values were typical of “educated Negroes” of their generation. They gave me the invaluable gift of being able to live with paradox: the confidence to experiment socially and sexually without losing my self-respect, to know that “difference” doesn’t have to be charted on an axis of superiority and inferiority, and that one can identify not only with other members of the black diaspora but any people who are exploited and rendered less than human without sacrificing one’s own sense of uniqueness and individuality.

Mad Men shows us again and again how socially and economically privileged Americans thought and, in many ways, how they continue to think and see themselves in the world. That the world of Mad Men is the advertising world—the world that shapes our desires and images of self—makes the ideologies of these characters more significant than those of the lawyers, UPS drivers, doctors, and police officers that people other television dramas. Mad Men were, and continue to be, powerful because they get inside our heads, and they assume the authority to articulate our desires. Mad Men were, and continue to be, primarily men from upper-middle and affluent families who went to selective colleges. Mad Men were, and continue to be, along with their counterparts in the entertainment industry, those most effective in shaping American society, values, and politics.

So no, I don’t enjoy Mad Men as a weekly exercise in nostalgia, nor do I appreciate it simply for its clear-eyed reminder of pre-feminist–movement life for educated white women and its tight and engaging scripts. Oddly enough, it’s a reminder of the world that formed me.

_________________________________________________________

Claire Oberon Garcia, a professor at Colorado College, teaches in the English Department as well as the Race & Ethnic Studies and Feminist & Gender Studies programs. She has published articles and book chapters on women modernists of the Black Atlantic and class, race, and gender issues in Henry James’s works. She is currently co-editing, with Charise Pimentel and Vershawn Young, Still Maids? Still Toms?: Perspectives on The Help and Other White-Authored Narratives of Black Life.

Claire Oberon Garcia, a professor at Colorado College, teaches in the English Department as well as the Race & Ethnic Studies and Feminist & Gender Studies programs. She has published articles and book chapters on women modernists of the Black Atlantic and class, race, and gender issues in Henry James’s works. She is currently co-editing, with Charise Pimentel and Vershawn Young, Still Maids? Still Toms?: Perspectives on The Help and Other White-Authored Narratives of Black Life.

40 Comments