Exposing the Invisible Betrayal: Removing the Gag from Our Mouths and Speaking of the Police Rapes of Black Women

By Guest Contributor on November 19, 2014By Farah Tanis

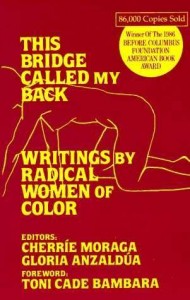

…cross over onto a new place where stooped labor cramped quartered down pressed and caged up combatants can straighten the spine and expand the lungs and make the vision manifest. ~ Toni Cade Bambara, This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color

Straightening the spine and making vision manifest despite the proverbial gag of our mouths, is what it sometimes feels like to be in this movement for racial justice. Crawling through electrical fences with razor sharp barbed wire, and scattered minefields stretched out for miles across communities, through homes and official buildings dictating what space Black women should take, what secrets Black women should keep, and what bodies should be put first, before ourselves is what it often feels like to be in this movement. With each attempt to blast the old locks off carefully constructed cages, we are reminded, that this is what it feels like to be in this movement for racial justice.

Straightening the spine and making vision manifest despite the proverbial gag of our mouths, is what it sometimes feels like to be in this movement for racial justice. Crawling through electrical fences with razor sharp barbed wire, and scattered minefields stretched out for miles across communities, through homes and official buildings dictating what space Black women should take, what secrets Black women should keep, and what bodies should be put first, before ourselves is what it often feels like to be in this movement. With each attempt to blast the old locks off carefully constructed cages, we are reminded, that this is what it feels like to be in this movement for racial justice.

Tell me, when has any freedom fighter, any human rights defender ever had to ask permission to speak up in protest? With or without your permission I have found the words. I have found the words to deploy as weapons in the war against my being sold-out by those I consider my kin, sold-out by my own community, and even at times by my own self. I have found the words of wise-militant Black feminists like Toni Cade Bambara—words seeding ideas, logic and strategy—as fuel to propel me, fists clenched, even with my back to the wall, ready for their strike-back, which almost always comes.

Tell me what freedom fighter, what human rights defender has ever had to ask—can I stand up? With or without your permission I’m already standing, cage doors flying open, my sisters’ strong fingers already pointing out the dangers we face as we traffic in and out of our communities, communities which still refuse to see us.

What freedom fighter, what human rights defender ever said—excuse me, but can I denounce this injustice? With or without your permission, I’m already exposing the hypocrisy of some who proclaim my struggle is interlocked with theirs, proclaim to accept me—cis gender woman, full of pride, full of pain, full of struggle inherited from generations of dark-skin women, from the bush of West-Africa, to Haiti, to Flatbush Avenue in Brooklyn. I’m already denouncing my being required to add my name to your lamentations about your abusers and bless your plight for freedom, while you refuse to acknowledge my very presence. I am required to stand by you and fight with you and for you, while you refuse to add your name in affirmation of my narrative, my life and the histories living within me.

I’m already breaking the codes, no longer operating under the radar, no longer “background figure”, “subordinate being” or “self-sacrificing”, unapologetically speaking of the individual and collective violations against us by police, by the state, by its institutions, against Black women like me. I have found the words, eyes bright blazing lights, my mouth shouting and inciting others to tell about the murders of Black women through the middle passage and the police rapes on the streets and in backs of patrol-cars in Oklahoma City, all while meditating on the words of Sister Toni Cade Bambara on the issue of roles in the movement, on male anxiety and women’s vilification—

I’m already breaking the codes, no longer operating under the radar, no longer “background figure”, “subordinate being” or “self-sacrificing”, unapologetically speaking of the individual and collective violations against us by police, by the state, by its institutions, against Black women like me. I have found the words, eyes bright blazing lights, my mouth shouting and inciting others to tell about the murders of Black women through the middle passage and the police rapes on the streets and in backs of patrol-cars in Oklahoma City, all while meditating on the words of Sister Toni Cade Bambara on the issue of roles in the movement, on male anxiety and women’s vilification—

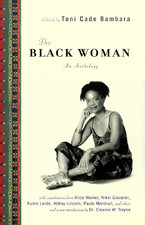

we rap about being correct, but ignore the danger of having one half of our population regard the other with such condescension and perhaps fear that that half finds it necessary to reclaim his manhood by denying her peoplehood. ~ Toni Cade Bambara, On The Issue of Roles, The Black Woman: An Anthology

Today, with or without your permission, Black women are armed with ancestral voices, our narratives, our testimonies and are speaking to the U.N. Committee Against Torture, for our foremothers whose bodies were tortured and were indeed as proclaimed by Sister Fannie Lou Hamer—“never theirs alone”. Black women are denouncing police rapes and sexual harassment as torture against us, across this nation, across generations by white slavers, white militia, roving gangs in white hoodies and burning crosses, night watchmen and “leatherheads” who policed early 19th century streets, who policed the woods and policed who we looked at, talked like, lived like; and more recently officer Daniel Holtzclaw discovered last summer, reported to have sexually assaulted approximately 13 Black women, and counting.

We will be heard, finally. For Black women in the United States specifically, fully accounting for the ways in which their experiences of sexual assault, or rape more specifically, constitutes an act of torture requires understanding the historical context and institutional legacy of slavery and the contemporary burden placed on victims of police sexual assaults. With that fact, Black women in the United States face a peculiar form of rape-based torture that has its origins in American slavery and the state apparatuses that evolve to protect the interest of the economic elites, white men, and public officials.

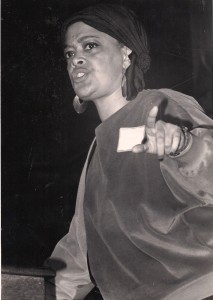

Toni Cade Bambara

Southern Rural Woman’s Network Conference, 1982

Photograph/Copyright: Monica F. Walker

While legal slavery has ended, the rape and sexual torture of Black women and the justification for this torture still continues. Contemporary gendered and racial profiling of Black women are rooted in the enforcement of Slave Codes, Black Codes, and Jim Crow segregation laws, which were state sanctioned practices that were a combination of de jure and de facto forms of social, legal, and economic laws, policies, and other constrains placed on Black people in the U.S. For example, “We Charge Genocide,” a petition submitted to the UN by the Civil Rights Congress in 1951, documented thousands of incidents of police violence against African Americans alone. While the modern Black civil rights movement ushered in a formal end to Jim Crow era segregation, it has taken decades to gain mainstream acknowledgement of the multiple and covert ways that racial apartheid functioned and affected Black women in the United States.[1] Michelle Alexander and a number of other contemporary scholars and advocates, for example, have documented the ways the criminal justice system still functions as a form of new Jim Crow.[2] Yet, for all the acknowledgement of this new-era racial apartheid and the terrorism of the police and criminal system officials, it has mainly functioned to raise the profile of the torture and deprivation of life of Black men.[3]

Tell me what freedom fighter, what human rights defender has ever had to ask—can I speak, can I stand up? With or without your permission I’m already speaking, already standing, cage doors flying open, my sisters’ strong fingers already pointing out the dangers we face as we traffic in and out of our communities, communities which we insist must see us—now.

No longer will silence prevail and the invisibility remain within Black communities and in greater society about Black women’s lives, about the level of sexual victimization, the systematic exclusion of our specific gendered experiences in the broader agenda for civil and human rights.

No longer will silence prevail and the invisibility remain within Black communities and in greater society about Black women’s lives, about the level of sexual victimization, the systematic exclusion of our specific gendered experiences in the broader agenda for civil and human rights.

We’re removing the gag to:

…cross over onto a new place where stooped labor cramped quartered down pressed and caged up combatants can straighten the spine and expand the lungs and make the vision manifest. ~ Toni Cade Bambara, This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color.

Black women are speaking about police rapes against us. Read the report: INVISIBLE BETRAYAL: Police Violence and the Rapes of Black Women in the United States

[1] “‘Apartheid is Flourishing’ in the US, says UN High Commissioner for Human Rights,” Available at http://www.presstv.com/detail/2014/08/20/375957/un-apartheid-is-flourishing-across-us/.

[2] Alexander, Michelle. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Era of Colorblindness. The New Press: New York, 2010.

[3] Ibid. In the book’s introduction, Alexander admits that this is mainly an examination of Black and Latino men, and more needs to be done to assess the treatment of Black women.

Farah Tanis is a transnational black feminist, women’s human rights activist and co-founder, Executive Director of Black Women’s Blueprint working at the grassroots to address the spectrum of sexual violence against women and girls in Black/African American communities, and working with Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) across the nation on issues of gender, race, sexuality, anti-violence policy and practice. Tanis launched and Chairs the first Truth and Reconciliation Commission in the U.S. ever to focus on Black women and their historical and contemporary experiences with sexual assault. She is founder and is lead curator at the Museum of Women’s Resistance (MoWRe), which in 2013 became internationally recognized as a Site of Conscience. Tanis created Mother Tongue Monologues, a theatrical and multimedia art vehicle for addressing Black sexual politics in African American and other communities of the Black Diaspora. Tanis is a 2012 U.S. Human Rights Institute Fellow (USHRN) and is a member of the Task Force on the U.N. Convention on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. Tanis served as Almoner for the Havens Relief Fund for seven years allocating emergency monies for women in need across the five-boroughs of New York City. Recently, Tanis served on the Board of Directors of Haki Yetu working to end Rape in the Congo region of Africa and the Board of Right Rides which provides safe rides home to women and LGBTQ people in New York City.

You may also like...

2 Comments

All Content ©2016 The Feminist Wire All Rights Reserved

Pingback: Afterword: Toni Cade Bambara's Living Legacy - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire