Personal is Political: TCB Is What She Did and Was Who She Was

By Guest Contributor on November 19, 2014By E. Ethelbert Miller

On March 3, 1995, I ran into Toni Cade Bambara. She was walking down the street near DuPont Circle (Washington, D.C.). I always admired this woman, and here she was sharing the sidewalk with me. Toni was the type of woman who could stop traffic. I think she was in town to listen to Toni Morrison (the recent Nobel Prize winner) give a talk on the campus of Howard University. I told her Morrison was probably already speaking, and Toni immediately decided we should just get some lunch. We can all be “Nobel,” can’t we? I remember this day, because she signed my autograph book. I had started carrying a Jacob Lawrence “Blank Book” and having writers sign something—a statement about our friendship or simply whatever came into their heads the moment I stopped them.

Toni wrote one of the longest entries. In it, she mentioned how she had once kept a similar book. In typical T-fashion, she said in her book people said anonymous nasty things about folks—and it was all big fun.

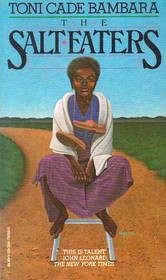

When I remember Toni Cade Bambara, I always think of a person who made me laugh until my belly ached. June Jordan did the same thing. I suspect our fingerprints were related. Along with these poet sisters being fierce—there was something beautiful about their wit and passion for life. In many ways, Toni was a visionary. I felt the first line of The Salt Eaters was the most prophetic thing any African American writer ever said.

Are you sure, sweetheart, that you want to be well?

These words were spoken by the healer Minnie Ransom to Velma Henry. This is a question we should ask ourselves today. We tend to be trapped within a non-changing racial narrative. How long must we view ourselves as victims? Don’t we want to be well? It seems we know what the historical diagnosis is; how dreadful slavery and legal segregation was. African American leaders keep proclaiming what Baraka saw in our music—“the changing same.” We seem stuck in race matters without a clue as to what medicine we should take.

These words were spoken by the healer Minnie Ransom to Velma Henry. This is a question we should ask ourselves today. We tend to be trapped within a non-changing racial narrative. How long must we view ourselves as victims? Don’t we want to be well? It seems we know what the historical diagnosis is; how dreadful slavery and legal segregation was. African American leaders keep proclaiming what Baraka saw in our music—“the changing same.” We seem stuck in race matters without a clue as to what medicine we should take.

I remember talking to the African American literary critic Arthur P. Davis shortly after The Salt Eaters was published—so it must have been around 1980 or 1981. Davis so much the southern gentleman simply couldn’t grasp the structure and tone of Bambara’s first novel. Some of Bambara’s work is blueprints for activism and global thinking. Was she ahead of her time? How is she remembered today?

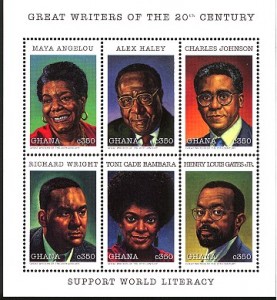

Back in 1997, I placed the portrait of Toni Cade Bambara on a stamp coming out of Ghana. It was a project I coordinated with Inter-Governmental Philatelic Corporation in New York. Some of the other writers I selected were, Richard Wright, Zora Neale Hurston, Alex Haley, and Maya Angelou. I saw them all as being great writers of the 20th century. The postage stamps were issued to promote literacy in emerging nations. Along with Ghana, Uganda also agreed to print stamps with the images of famous African American writers.

Back in 1997, I placed the portrait of Toni Cade Bambara on a stamp coming out of Ghana. It was a project I coordinated with Inter-Governmental Philatelic Corporation in New York. Some of the other writers I selected were, Richard Wright, Zora Neale Hurston, Alex Haley, and Maya Angelou. I saw them all as being great writers of the 20th century. The postage stamps were issued to promote literacy in emerging nations. Along with Ghana, Uganda also agreed to print stamps with the images of famous African American writers.

Bambara had a direct influence on my own work. It was at the National Conference of African American writers held on the campus of Howard University in 1974 that she read her short story “Gorilla, My Love.” I fell in love with her voice, its cadence capturing the sound of young people. It was like hearing Charlie Parker playing “Cherokee” for the first time. My ears were never the same. When I wrote my “Omar” poems, and presented a young Muslim boy on the page, it was an outgrowth of having listening to Toni. Present in all the “Omar” poems is the humor and the moral courage Bambara instilled in her child characters. I wanted my voice to dance with Big Brood and Baby Jason. Call me—Hunca Bubba.

Toni, my love—I miss you terribly.

E. Ethelbert Miller

September 24, 2014

E. Ethelbert Miller is a writer and literary activist. He is board chair of the Institute for Policy Studies and the director of the African American Resource Center at Howard University. He has published several collections of poetry and two memoirs. Mr. Miller is often heard on National Public Radio.

E. Ethelbert Miller is a writer and literary activist. He is board chair of the Institute for Policy Studies and the director of the African American Resource Center at Howard University. He has published several collections of poetry and two memoirs. Mr. Miller is often heard on National Public Radio.

You may also like...

2 Comments

All Content ©2016 The Feminist Wire All Rights Reserved

Pingback: Afterword: Toni Cade Bambara's Living Legacy - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire