Personal is Political: Re-Imagining Disclosure as a Collective Act of Listening

By Tennessee Watson

April marked my 14th year as a public survivor of child sexual abuse. My process of disclosure, one of coming out and letting in, started at the Take Back the Night March during my first year at Colby College in Waterville, Maine.

April marked my 14th year as a public survivor of child sexual abuse. My process of disclosure, one of coming out and letting in, started at the Take Back the Night March during my first year at Colby College in Waterville, Maine.

It’s a journey that’s resulted in the creation of the Autonomous Memory Front, which is a collaborative effort to create moments where survivor disclosure shifts from being a solitary and spectated act to a collective process. I created it because I didn’t want to be alone, but it’s a hard truth to want to share. How could I connect with the survivors I knew were all around me? What if my powerful proclamations were an unforeseen catalyst of reengagement with childhood trauma for another adult survivor? So for years I let myself be just one—the solitary body in the info-graphics on child sexual abuse: static, disconnected and different from the bodies surrounding me.

I was the 1 in 10. I was alone, surrounded by a hypothetical group of nine people, who were somehow unaffected. As a woman I am less distinct. I was alone in the company of three. I was only one of four.

These statistical renderings hide our stories, and leave our communities undefined. It ignores the impact of child sexual abuse on our family and friends. I don’t want to dispense with statistics, but I want the movement to complicate how we use them. We need to leverage data to show our power and connection, but resist letting it exist as definitive representation of the problem we face when we know there is so much that numbers leave out.

Experts tell us those numbers are likely low. Yet our uncertainty about the issue’s prevalence is often attributed to how few victims disclose or report their abuse.

Why do we wait for disclosure, as opposed to engaging each other, and having the hard, but necessary conversations, about the impact of child sexual abuse? The Autonomous Memory Front tries to break away from how violence and trauma are typically revealed, creating moments where we get to experiment with different ways of sharing our experiences.

I want the movement to shift away from such heavy emphasis on survivor disclosure, away from the idea that the onus is on survivors to speak out in order to end this silent epidemic.

Sure feminism urged me to activate my voice and get loud, as a reclamation of my power and resistance to my own oppression, but I also spent years feeling like I wasn’t down for the cause because no where did I see the other ways I was resisting reflected back to me as legitimate. The message I heard loud and clear was that my silence was the problem.

Aimee Carrillo Rowe and Sheena Malhotra edited an incredible anthology of essays entitled Silence, Feminism, Power: Reflections at the Edges of Sound, which interrogates this often-unexamined assumption that silence is oppressive, and considers the multiple possibilities silence enables. The equation between voice and power informs feminist theory and activism, creating an imperative that the oppressed must “come to voice.” I have to thank Malhotra and Rowe for articulating that the problem with “this formulation is that the burden of social change is placed upon those least empowered to intervene in the conditions of their oppression. The figure of the subaltern, or the survivor, gaining voice captures our political imaginary, shifting the focus away from the labor that might be demanded of those in positions of power to learn to listen to subaltern inscriptions—those modes of expression that are often interpreted as ‘silence.’”

Aimee Carrillo Rowe and Sheena Malhotra edited an incredible anthology of essays entitled Silence, Feminism, Power: Reflections at the Edges of Sound, which interrogates this often-unexamined assumption that silence is oppressive, and considers the multiple possibilities silence enables. The equation between voice and power informs feminist theory and activism, creating an imperative that the oppressed must “come to voice.” I have to thank Malhotra and Rowe for articulating that the problem with “this formulation is that the burden of social change is placed upon those least empowered to intervene in the conditions of their oppression. The figure of the subaltern, or the survivor, gaining voice captures our political imaginary, shifting the focus away from the labor that might be demanded of those in positions of power to learn to listen to subaltern inscriptions—those modes of expression that are often interpreted as ‘silence.’”

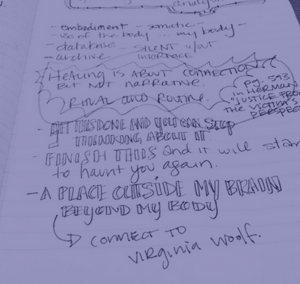

I wanted to create a space to document and record resistance and resilience that isn’t being seen or heard; the thoughts, the memories, the moments of strength that we want to share, but without putting ourselves on blast as survivors. And to be honest I created this project so I could ask people about their experiences with child sexual abuse, but with some space and distance because I was feeling shy and uncertain about coming right out and asking people. I was scared to ask because I was scared that I might trigger something or traumatize someone.

So I created an archive that uses an automated hotline to record thoughts, instincts and impulses that emerge in response to trauma, and preserves them as collectively voiced statements. My collaborator, Yeshe Parks, custom designed software that breaks the original submissions, in a singular voice, down into individual words and then reassembles them using the voices of other contributors.

The Autonomous Memory Project refuses to let the abused body hold trauma alone. It gives us a way to perceive how violence reverberates and how resilience echoes through us all. It gave me a way to speak out with other people. Disclosing my story to my community came through the creation of a collective endeavor and that somehow felt less heavy. It provided a way for me to talk and for people to talk to me, and ask me about the experience.

I was seven when it happened. I held that truth, not knowing what to do with it, for 12 years. In part I blame feminism for that paralysis, but I also give feminism credit for my eventual action.

Because of the Riot Grrrl scene, and ancestresses like Virginia Woolf, Gloria Anzaldúa and Audre Lorde, I was assured that if I spoke out a courageous community of survivors and allies would accompany me through the process. But I also knew that speaking out meant potentially engaging the cops where a detective in the Special Victims Unit might investigate my case. Special and victim do not fit with my feminist understanding of myself. I wanted to pursue accountability and justice without perpetuating childhood sexual abuse as an isolated incident implicating only a victim and a perpetrator, and without perpetuating an approach to violence relegated to confrontation on a case-by-case basis.

Because of the Riot Grrrl scene, and ancestresses like Virginia Woolf, Gloria Anzaldúa and Audre Lorde, I was assured that if I spoke out a courageous community of survivors and allies would accompany me through the process. But I also knew that speaking out meant potentially engaging the cops where a detective in the Special Victims Unit might investigate my case. Special and victim do not fit with my feminist understanding of myself. I wanted to pursue accountability and justice without perpetuating childhood sexual abuse as an isolated incident implicating only a victim and a perpetrator, and without perpetuating an approach to violence relegated to confrontation on a case-by-case basis.

Figuring out how to infuse this larger political agenda into the telling of my personal story became the primary force slowing down my desire for public disclosure. I wanted to communicate the isolating and destabilizing impact of trauma, but I didn’t want to be read as a powerless victim or a sick freak because of my exposure to sexual violence. I couldn’t think about speaking without worrying about how I would be heard. My mind craved moments where my thoughts, memories and mental impulses had autonomy from an interpretation of their intent or implication.

The reverberations of trauma are something I’ve dealt with all my life. They are brought on by the memories of what happened, but also by the shame I feel for not speaking up, for betraying my own instincts to act in response to the violation of my body. There was so much pressure to speak and yet no one was asking me. If more people had asked it might have mitigated the trauma of not being able to speak.

Feminist scholar Ann Cvetkovich found that “many narratives by survivors […] indicate that the trauma resides as much in secrecy as in sexual abuse—the burden of not to tell creates its own network of psychic wounds that far exceed the event itself. By the same token, the work of breaking the silence about sexual abuse, like that of coming out, has to be understood as an ongoing process and performance, not as a punctual event.”

And that means we can’t just ask once. We need to keep showing up for each other. It’s about pushing everyone to be more vocal, while at the same lifting up other forms of resistance. Celebrating the moments where we walk away, where we set boundaries, where we feel proud to make ourselves feel safe and don’t pathologize our behavior as paranoid or neurotic. And it’s about asking and accepting the pause, accepting the awkward silence, and holding that space, and trusting survivors’ strength and agency.

I’ve been hesitant to ask friends and family if they also share this experience with me. I hold back out of fear of triggering them, or resurfacing their trauma. But the trauma is there no matter what, and ultimately the compassionate inquiry of a friend is not the cause of my trauma. That designation is reserved only for the perpetrator of the abuse.

Having these conversations means trusting that we are strong enough and smart enough to figure out how to engage these hard truths and use them to catalyze action.

Do me a favor: Tell your friends about the Autonomous Memory Front. Use it as a way to ask about the impact of child sexual abuse on their lives, families and communities. And then call the hotline: 518-314-9675, and leave a message about how it felt to break silence by listening out. Or if you’re not ready to start that conversation call the hotline and tell us what is going through your head. At times isolation and silence might be part of our resistance.

Do me a favor: Tell your friends about the Autonomous Memory Front. Use it as a way to ask about the impact of child sexual abuse on their lives, families and communities. And then call the hotline: 518-314-9675, and leave a message about how it felt to break silence by listening out. Or if you’re not ready to start that conversation call the hotline and tell us what is going through your head. At times isolation and silence might be part of our resistance.

What unites us is our hope for the healing affect of disclosure, not as the spectated act of telling one’s truth, but as a process of collective “sense-making” and that process of sense-making means we must ask questions, we must speak, we must sit quietly and silently—at times—and just listen.

I end with this poem:

seldom do we choose disclosure

not right away

our silence is sly, uncertain

no visible signs of resistance

a strategy we share

with certain snakes and spiders

an apparent death

a sign of subjection

or a snare

cunning and subversive

camouflaged

by silence and stillness

so deep and deceiving sometimes

we can not even see each other

we count the mornings

he wakes up wondering

today will she speak

we are slick

but sick of feeling alone

so we speak

still secretly plotting

through the coded

sharing of words

till we find each other

_________________________________________________________

Tennessee Jane Watson is an instigator, artist, activist, and public survivor. As an award-winning documentary media producer, her creative practice focuses on finding creative and supportive ways to encourage us to think and act in transgressive ways. She is currently publicizing her latest project, The Autonomous Memory Front, an interactive audio archive that challenges how the movement to end child sexual abuse has historically approached silence, and that re-imagines the politics of survivor disclosure.

Tennessee Jane Watson is an instigator, artist, activist, and public survivor. As an award-winning documentary media producer, her creative practice focuses on finding creative and supportive ways to encourage us to think and act in transgressive ways. She is currently publicizing her latest project, The Autonomous Memory Front, an interactive audio archive that challenges how the movement to end child sexual abuse has historically approached silence, and that re-imagines the politics of survivor disclosure.

3 Comments