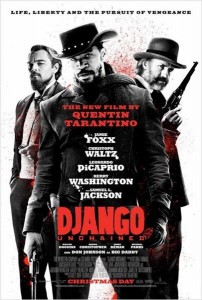

Django Unchained: A Critical Conversation Between Two Friends

By David J. Leonard and Tamura A. Lomax

There have been so many great discussions on Django Unchained, so many thoughtful and engaging articles, and even more critical engagements within social media. We’ve seen everything from harsh critiques to high praise, and of course everything else in between. The analyses, conversations and comments have all been challenging. Rather than write a review per se, we thought we’d have a public conversation. Regardless of how we individually interpret the film, we agree that Django needs lots of discussion. There’s still a fair amount of unsullied ground to cover, or perhaps, previously examined ground to rehash. Whatever the case may be we invite you to join us.

There have been so many great discussions on Django Unchained, so many thoughtful and engaging articles, and even more critical engagements within social media. We’ve seen everything from harsh critiques to high praise, and of course everything else in between. The analyses, conversations and comments have all been challenging. Rather than write a review per se, we thought we’d have a public conversation. Regardless of how we individually interpret the film, we agree that Django needs lots of discussion. There’s still a fair amount of unsullied ground to cover, or perhaps, previously examined ground to rehash. Whatever the case may be we invite you to join us.

DJL: Let me start with this: I am not a fan of Quentin Tarantino (QT), Westerns, or action films. This is not my wheelhouse so it is no wonder that I left the movie with both questions and concerns about its message and representations, and a MEH feeling about the film. I just didn’t feel it. More importantly, I find QT to be really arrogant and problematic as a filmmaker and as a PERSONA on a number of levels. His responses to critics, his self-aggrandizement, his lack of critical self-reflection, his lack of growth as a filmmaker (the fact that this film is so much like his past films is not a ringing endorsement), and his comfort in cashing in on his privileges trouble me. My reading of the film is clouded by all of these feelings.

TAL: David, let me begin by saying, “I hear you.” I hate almost all kinds of violence so I never got into QT’s films. I don’t have any preferences for action films either, and Westerns always registered as “white” in my mind. However, I loved this film! To be sure, there are numerous problems with both QT and the film. And I get your critique of QT’s persona. He absolutely comes across as self-aggrandizing, and perhaps even unreflective. One thing is for sure though, QT is very much aware of his privilege. That is, he seems to understand quite well who gets to tell what story in Hollywood, and who and what’s needed for authentication. That aside, I still loved this film. I read it as a love story—one marred by both life and death of course.

DJL: Speaking of violence, the violence in the film felt gratuitous at times. It was often more spectacular than a critique of white supremacist violence. There were moments where the cinematic gaze was infused with a pleasure in the violence, and that troubled me. Those scenes were early in the film – the scene involving the dogs, and slave fights — and I had to look away because the purpose seemed to be about eliciting pleasure from its (white) viewers. The camera’s gaze conveys pleasure and joy in these spectacular images. It didn’t feel as if there was an interest in conveying outrage and spotlighting trauma. Rather there seemed to be an effort to bring viewers into this extreme spectacle of violence. The lack of reflection in the cinematic gaze angers me. I think about the times that I have taught about the Birmingham church bombing, Emmett Till, and the history of lynchings, and how I have thought long and hard about the pain and trauma. Sometimes unsuccessful, I have looked inward in these moments, thinking how might whiteness matter when recounting these histories. I don’t feel like QT accounted for the trauma or this history.

DJL: Speaking of violence, the violence in the film felt gratuitous at times. It was often more spectacular than a critique of white supremacist violence. There were moments where the cinematic gaze was infused with a pleasure in the violence, and that troubled me. Those scenes were early in the film – the scene involving the dogs, and slave fights — and I had to look away because the purpose seemed to be about eliciting pleasure from its (white) viewers. The camera’s gaze conveys pleasure and joy in these spectacular images. It didn’t feel as if there was an interest in conveying outrage and spotlighting trauma. Rather there seemed to be an effort to bring viewers into this extreme spectacle of violence. The lack of reflection in the cinematic gaze angers me. I think about the times that I have taught about the Birmingham church bombing, Emmett Till, and the history of lynchings, and how I have thought long and hard about the pain and trauma. Sometimes unsuccessful, I have looked inward in these moments, thinking how might whiteness matter when recounting these histories. I don’t feel like QT accounted for the trauma or this history.

TAL: I concur. There was a lot of violence in the film, more than I could stand. But slavery was violent. Our current context is violent. But let me just say this, the continuous cannonades of blood were odious hands down. Still, I think it’s important to keep in mind that, in a captive state, death often marks the point of transition between modes of servitude and inter-subjective states of liberty. Thus, while the violence in the film was at times overwhelming, and although I really do detest violence, I was admittedly okay with some of it. I think the problem with QT, in addition to those you mentioned, is that his gaze too often waxes and wanes between voyeurism, fetishism, condescension, and black heroic genius. On one hand we get Django, a hero of sorts who kills for love and vengeance. And on the other hand, we get everyone else, a collection of seemingly disposable frozen objects who, among other things, seem cool on not only their enslavement, but the routinization of violence against black humanity around them. Along with some of the images of death, I found this to be deeply problematic.

Some of the scenes were so gruesome that, in addition to looking away and/or covering my ears, I had to take a mental moment. As you’ve stated, QT delivers violence, perhaps even takes pleasure in it, however he doesn’t take the time to deal with or allow us to sit with the trauma. He doesn’t allow us to feel the pain of the characters; he doesn’t encourage viewers to reflect on the psychic pain of black death or the countless victimizations of white supremacy. We should problematize all of this, but perhaps QT’s offering us a mockery on life. Sometimes we take pleasure in hideous violence (isn’t this why it’s videotaped so rampant and callously?). Sometimes we find alibis for engaging the taboo. Sometimes violence is selfish. Sometimes it’s unprovoked. And sometimes it’s illiberal. However, sometimes violence may be just, cathartic, or imagined as some sort of source of power. What happens when, for a great many of us, our origins as subjects are entangled with what we refer to as violence? This is a winding conundrum.

DJL: The final scene in the film was exhilarating. The sight of Django blowing away white oppressors, obliterating a white plantation, and seeking revenge and retribution is most certainly a source of power. In the context of cinema that privileges violence, that privileges individual heroism conquering evil, the prospect of this narrative being deployed within the context of slavery, is a source of power. Yet, I also felt myself thinking about the other freed slaves within the film; what might have happened to them as they fled Candie’s destroyed plantation or as they escaped the mining company? Are they unchained?

TAL: We don’t know. I thought the same and had similar questions. But, what of the power of individual fantasy? I imagined that they effortlessly stole away and gained their freedom. I couldn’t bring myself to imagine any more violence. But let’s be clear, what’s being presented here, although in some ways liberative, isn’t a historical narrative. It’s more so what bell hooks calls “fictive ethnography.” We want there to be truths, we want there to be historical connections, and we want the story to be told in a certain fashion. For some this means disciplining the word, “nigger,” and for others it means complexifying not only the institution of slavery, but the enslaved women in the film.

DJL: QT defends his use of the “N-Word” by arguing that it is historically accurate, that it reflects the racial im(morality) and violence of Texas, Tennessee, and Mississippi in the 1850s. He shrugs off criticism (dismissing it in fact):

Personally, I find [the criticism] ridiculous. Because it would be one thing if people are out there saying, ‘You use it much more excessively in this movie than it was used in 1858 in Mississippi.’ Well, nobody’s saying that. And if you’re not saying that, you’re simply saying I should be lying. I should be watering it down. I should be making it more easy to digest. No, I don’t want it to be easy to digest.

Others have offered a similar defense, although I have a hard time with this argument for a couple reasons: QT and his defenders simultaneously invoke history and deny that Django is a movie based in history. Whereas the endless other historic omissions, mythologies, and falsehoods (for example where is evident of the Black Codes) are OK because this is a Spaghetti Western or because this is a QT production, but the “N Word” makes sense because of history. I raise this issue not so much to question its usage but rather to question the hypocrisy from QT who seems to invoke history when it is convenient. He includes the “B-word,” which was not widely used until 1920 and “MF,” which wasn’t in common use until World War II. Historic accuracy doesn’t really seem to be a concern. The decision not to include scenes of sexual violence (though they were in one version of the script), which is understandable, also doesn’t seem to wash with the mandate of making a movie that isn’t easy to digest.

The fact that QT uses the word in virtually every movie should at least give pause that its deployment in Django cannot be chalked up to historic accuracy or the time/space that the film takes place. Joel Randall makes this clear, identifying the pattern of usage (200 times in 6 films) in his entire body of work:

You’ve obviously been suffering withdrawal from your beloved n-word, because you’ve returned to overusing the word seemingly on steroids. You volley the n-word around in Django Unchained over 110 times, all under the guise of “historical accuracy.” But that’s bullshit. You’re not concerned about being historical or accurate. You just have some sick obsession with the n-word, and it’s way more racist than historic. Here, let me show you, as we take a walk down memory lane through your employment of the n-word like it was the most privileged extra in Hollywood.

In the end, I find QT’s use of the N-Word in this film, and in many others (not historically contingent) to be part of his fetishizing of blackness. The ability to say the word, to do what other whites are purportedly not able to participate in, becomes an instance where he becomes the embodiment of the exceptional white body. He becomes cool, he becomes racially progressive, and he becomes the hipster white dude that can say the N word and get away with it.

TAL: I have different views in terms of the deployment of language with regard to who get’s to say what.

DJL: Tell me more. How so?

TAL: First, I concur with your assessment of QT’s contradictions and sense of privilege and entitlement. However, I think I’ve developed a certain callousness to the word. I actually found its deployment quite normative.

DJL: I wonder how QT has been part of this normative process, although doing little to actually foster justice and equality. Say more.

TAL: This is layered and I’m actually saying a lot here, but the crux of what I’m saying really highlights my politics of language and interpretation of signs, symbols, significations and representations. Words and images have power. Moreover, they signify the various meanings that we give to them. And, meanings, no matter how hard we try, can neither be buried nor frozen in time. Nor can they be possessed. We can’t control them once they’re uttered into the atmosphere, and we cannot regulate their various appropriations. QT’s deployment and meaning differs from Fox’s and others. And I’m in no way diminishing the power and problematics of the word. I’m just saying there’s a linguistic complexity here that we rarely deal with. In short, words, whether it’s nigger, niggaz, nigga, or n-word, are signs made up of symbols (a, b, #, ^) with their very own cosmic space and histories. They’re all very different…and out of our control. So, as much as we’d like, we can’t put them to rest or regulate their deployment or meanings. We can try. However, it hasn’t worked. We can, however, continue to call out and interrogate the circulating archives of racial knowledge and cultural practices that continue to attach injurious signifiers to living bodies.

DJL: I see. I want to come back to this if we have time, or perhaps revisit offline. This is truly a discussion within a discussion, or maybe even a discussion unto itself. There’s a lot here. In the meantime, let’s talk more about the film.

Jamie Foxx was powerful as Django. He offered cinematic disdain to the tenets and history of white supremacy. Sitting on top of a horse, looking down upon white oppression, Django refused and resisted the violence and dehumanization of white supremacy throughout the film. Yet, at times his character felt like QT’s fantasy, a racial cross-dressing fantasy for himself; the centrality of cool, the camera’s gaze upon his body, particularly his penis, and the importance of violence, leaves me questioning how Django embodies QT’s racial fantasy, a longing to embody those qualities that he sees and locates within blackness.

Jamie Foxx was powerful as Django. He offered cinematic disdain to the tenets and history of white supremacy. Sitting on top of a horse, looking down upon white oppression, Django refused and resisted the violence and dehumanization of white supremacy throughout the film. Yet, at times his character felt like QT’s fantasy, a racial cross-dressing fantasy for himself; the centrality of cool, the camera’s gaze upon his body, particularly his penis, and the importance of violence, leaves me questioning how Django embodies QT’s racial fantasy, a longing to embody those qualities that he sees and locates within blackness.

TAL: Honestly, I almost fell out of my seat when Django appeared in his royal blue and cream peacock aesthetics. This is an undeniable aspect of black culture. When given the means and opportunity, black folks are known to take style to not only the next, but the next, next level—sometimes to levels of [what is deemed as] absurdity. I’m willing to bet that that costume was Fox’s idea. I thought it was comedic genius. This reading doesn’t negate the possibility of fantasy, however. Strong, naked, black male bodies were interestingly in abundance in the film while naked black female bodies were not. And I’m quite honestly thankful for the latter. I also appreciated the fact that QT gave us black sexuality without the visual of rape as its normal mode of deployment. There were several moments in the film where black women could have been taken as conquests by Django and others. We didn’t even get a lovemaking scene between Django and Broomhilda. I’m on the fence in terms of my feelings there. I have no idea what QT’s overall intentions were. Still, I appreciate some of them.

DJL: What about QT’s gender politics? I think they’re awful; I don’t think Kerry Washington could have been less utilized. As a huge fan of her work, especially in Scandal, I was truly frustrated by her character. She deserved more in the film.

In fact, the failure to offer any female characters of depth is not surprising given his body of work. The conventional “man saves women” also gives me pause in part of because of the media narrative as to how unconventional and challenging QT is within the national landscape, yet when it comes to gender, when it comes to his recycling of patriarchal fantasies, Django gives viewers more of the same.

TAL: I want to deal with the gender issue first. I’ll move to the male savior figure after. I’ve seen numerous critiques of QT’s gender politics re: this film. I actually do not agree with half of them. Was Washington’s talent underused? Perhaps. Could the women characters in the film exhibit more complexity, at least a complexity that aligned with the male characters? Certainly. However, was Broomhilda’s character flat? Not in the least.

Many have reduced Broomhilda to a damsel in distress foil for QT’s knight and shining armor trope. I totally disagree with this. Sure, she doesn’t say much. Yet, to my mind, Broomhilda’s silence is absolutely verbose. She speaks. Of course we never gain access to Broomhilda’s entire story. Nevertheless, her screams, shrieks, trembles, posture, lacerations, and tears say so much. They tell us, if nothing else, that Broomhilda is more than a beautiful woman trapped in the middle of a violent love story and cinematic dream sequences. And she’s certainly more than what Hortense Spillers once coined as “captive flesh.”

Many have reduced Broomhilda to a damsel in distress foil for QT’s knight and shining armor trope. I totally disagree with this. Sure, she doesn’t say much. Yet, to my mind, Broomhilda’s silence is absolutely verbose. She speaks. Of course we never gain access to Broomhilda’s entire story. Nevertheless, her screams, shrieks, trembles, posture, lacerations, and tears say so much. They tell us, if nothing else, that Broomhilda is more than a beautiful woman trapped in the middle of a violent love story and cinematic dream sequences. And she’s certainly more than what Hortense Spillers once coined as “captive flesh.”

Broomhilda is human. Not only is she resistant, her unbridled quest for freedom suggests that she’s also keenly aware of her self worth. In addition, she has an opportunity to not only love deeply, but to have that same sort of love designated just for her in the universe through Django. Who doesn’t want that, and when’s the last time that we’ve seen this in pop culture? I know there’ve been a lot of Spike Lee/QT comparisons with this film, but truthfully, do we get this sort of inter-subjective density from Colleen Royale, the mother from Red Hook Summer, who dispatches her son to the city to live with his grandfather for the summer, a fire and brimstone preacher and known pedophile?

Broomhilda is human. Not only is she resistant, her unbridled quest for freedom suggests that she’s also keenly aware of her self worth. In addition, she has an opportunity to not only love deeply, but to have that same sort of love designated just for her in the universe through Django. Who doesn’t want that, and when’s the last time that we’ve seen this in pop culture? I know there’ve been a lot of Spike Lee/QT comparisons with this film, but truthfully, do we get this sort of inter-subjective density from Colleen Royale, the mother from Red Hook Summer, who dispatches her son to the city to live with his grandfather for the summer, a fire and brimstone preacher and known pedophile?

There are moments in life where the rhetoric and/or reality of protection are needed, I think. When thinking about the rhetoric of protection and the male savior trope in this film, it’s imperative to think about each in terms of the experiences of captive flesh within patriarchal structures. And I get the whole exceptionalism argument. However, it’s also historically appropriate to suggest the desire or need for a savior figure or hero in this instance. The quest for male (and sometimes female) savior figures weren’t uncommon to the enslaved. Truth be told, they’re not uncommon now. This is why Tyler Perry is so popular. He’s mastered the whole Christian-Christ-male-savior concept, however you read it. Patriarchal, heterosexist problems aside, heroes are sometimes needed, especially when surrounded by a sea of villains. Why not the love of Broomhilda’s life? The fact that Django risks everything to free his beloved is nothing short of intoxicating. And the moment where he, instead of a rapist-murderer, enters the cabin to take Broomhilda away is beyond potent, and not because she wasn’t a fighter, but because she needed help making an exit route. Survivors of violence can only wish for such a moment—for love to arrive before violence takes hold.

There are moments in life where the rhetoric and/or reality of protection are needed, I think. When thinking about the rhetoric of protection and the male savior trope in this film, it’s imperative to think about each in terms of the experiences of captive flesh within patriarchal structures. And I get the whole exceptionalism argument. However, it’s also historically appropriate to suggest the desire or need for a savior figure or hero in this instance. The quest for male (and sometimes female) savior figures weren’t uncommon to the enslaved. Truth be told, they’re not uncommon now. This is why Tyler Perry is so popular. He’s mastered the whole Christian-Christ-male-savior concept, however you read it. Patriarchal, heterosexist problems aside, heroes are sometimes needed, especially when surrounded by a sea of villains. Why not the love of Broomhilda’s life? The fact that Django risks everything to free his beloved is nothing short of intoxicating. And the moment where he, instead of a rapist-murderer, enters the cabin to take Broomhilda away is beyond potent, and not because she wasn’t a fighter, but because she needed help making an exit route. Survivors of violence can only wish for such a moment—for love to arrive before violence takes hold.

It’s also important to note that Broomhilda is an ex-slave woman who’s been violated, and faces the threat of continued violation, not a woman born into a context of choice, rights and privilege. We typically understand and problematize the rhetoric of protection, chivalry, etc., in light of the latter, where savior tropes function more so as middle class patriarchal controls. However, Broomhilda’s captivity, and that of others, pushes us to reimagine Django not as a knight in shining armor male savior trope, but a representation of fugitive justice. This is a source of hope for the racialized, both captive and post-captive.

It’s also important to note that Broomhilda is an ex-slave woman who’s been violated, and faces the threat of continued violation, not a woman born into a context of choice, rights and privilege. We typically understand and problematize the rhetoric of protection, chivalry, etc., in light of the latter, where savior tropes function more so as middle class patriarchal controls. However, Broomhilda’s captivity, and that of others, pushes us to reimagine Django not as a knight in shining armor male savior trope, but a representation of fugitive justice. This is a source of hope for the racialized, both captive and post-captive.

DJL: Tamura, this is brilliant. You have given me a lot more to think about and I have actually thought about the film a lot, which is interesting given how much I didn’t feel the film.

In fact, I have thought long and hard about how my ambivalent reaction to the film (at some level my dislike of the film) is conditioned by my own whiteness; that white privilege infects my gaze so much so that the emotionality, the appeal, and the power of a black hero, a hero like Django whose swagger, aesthetic, and refusal to take any shit from white America means something different to me. In a society, in a cinematic landscape, where white masculinity is validated, celebrated, and elevated, I recognize that my reaction to the film is clouded by the privileges of whiteness.

TAL: Absolutely. My reading is certainly coloured by my position as a black woman. I think it’s good to stop for a moment and acknowledge that. All of our readings are ‘positioned.’

DJL: Final thoughts?

TAL: I loved how the film turned slavery on its head. I know that Ishmael Reed critiqued this film, but QT presented his “slavery” in the spirit of Reed’s Flight to Canada (perhaps QT is more of a mixture between Harriet Beecher Stow and Reed). Django isn’t a revolutionary figure in the way we might imagine Nat Turner or Denmark Vesey. Still, QT’s protagonist and “slavery” are iconoclastic. Everybody gets to be a nigger, that is, flesh for cash. Moreover, regardless of what we may think of QT’s racial politics, his parodies of whiteness, the Klan, master-class incest, white brilliance, etc., are disruptive. They provide a different kind of narrative, further revealing the human-made character of racism, thus allowing us to find humor in the demonic. The presence of the comedic in no way diminishes the cruelty of history. We’re too clever for that. Black folks have long used jokes to lessen the racial yoke. We don’t always have to (or want to) relive the tragic. Sometimes comedic rage works just fine. And rest assured, meaning is never limited to the producer. We’re always rearranging signs and symbols in order to make the most sense out of them. What are your final thoughts?

DJL: People often lament or dismiss social media as an echo chamber, where the same voices and opinions get circulated over and over again. The discussions and debates, the myriad of amazing articles dealing with Django, points to the critical discussions and expansive horizons postulated in these spaces. As much as I walked out of the theater frustrated, angered, and full of questions, I find myself wanting to watch the film again, to digest each and every POV about the film. I just hope QT and those viewers, who may have laughed in inappropriate moments, find their way into these spaces to join in these conversations.

20 Comments