Riding Past the Limits of Coalition Politics

By Juliana “Jewels” Smith

For the first time since I was a teenager, I started riding my bike when I was in graduate school at UC San Diego. George W. Bush was in office, gas prices had gone over $2 per gallon, and I felt like the apocalypse was surely close. I decided I was going to get a new (used) bike to start my commuting to and from school. And I wasn’t too serious about my bike choice. I would get passed on the streets by cyclists with fancier 22-gear bikes that made the zzzzzsss sound even when they weren’t pedaling. I was a novice when it came to bike riding, but that did not make me any less enthusiastic about my new whip. The bike became a daily fixture in my commute and life. Getting from point A to point B was my goal and this was the most practical and effective way.

During the time I rode my bike in San Diego, I had seen very few, if any, Black bike riders. But when I finally moved back home to the Bay Area, it was more of the same. There were a few more Black bike riders, but I figured that was just because population-wise there were more Black people. I always wondered why there were not more Black folks on bikes given the current state of things.

It was not until I met Jenna Burton in the first few months of being in the Bay Area that I realized I was not alone in my observation. Burton had started a relatively small group called Red, Bike and Green (RBG), a cycling group for Black folks. I had long thought about the possibilities of having a critical mass of Black bike riders, mostly after my musings over what it would feel like to ride with Black folks instead of the racially homogenous Critical Mass in San Diego. I started organizing with Red, Bike and Green right away because I was excited about the possibilities of a whole bunch of Black folks on bikes.

This was a large shift for me. Before organizing with Red, Bike and Green, biking was a way to maneuver around town without spending a whole bunch of money on gas. Riding bikes was not my activist take on Oil Wars, corporate-driven policies, or even US foreign (un)diplomacy. In the nascent years of doing activism, my focus centered in and on the prison industrial complex.

During the time I had been involved, I distinctly remember very few Black folks organizing with me. Again, I figured it was because the university I attended did not have that many Black folks. Either way, I was still drawn to the possibilities of multiracial organizing on issues that I felt were best addressed through solidarity across community lines, as in the case of police brutality and anti-globalization campaigns. I still am in a way. There is a part of me that wants to believe in the manifestos of coalition politics that circulated during my formative years in the 1990s and early 2000s, but the failures of those tactics are brought into sharp relief when I think about the specific realities of Black folks in this country.

Racism manifests in a way that is both spectacular and mundane. It is spectacular for its hyper police state-sanctioned and vigilante violence toward Black people, its high rates of murder in places like Oakland and Chicago, and the high arrest and imprisonment rates for African American youths and adults in California. This violence is also mundane for its ability to literally make or break public policies like welfare or to enact silence surrounding the murders in Oakland and Chicago. Perhaps even more insidious is the banality of anti-black racism in the form of progressive politics.

As I think about the work I have done in activist spaces, there is a way that people-of-color (PoC)/progressive organizing seduces us into thinking we are in solidarity around “the issues,” rather than specifically addressing the anti-black racism that underlies those social problems— and indeed modernity itself. Not enough bike lanes. Not enough affordable housing. Not enough adequate health care. PoC/progressive spaces address these issues in ways that disembody them from the folks who Jared Sexton calls the “prototypical targets of state violence,” Black people. This conscious or unconscious refusal of PoC/progressive groups to acknowledge the exceptional ways that anti-black racism shapes political demands is what Sexton calls “people-of-color-blindness.”

On the one hand, the most legitimate organizing is seen as multiracial. In this way, the sole raison d’être for Black participation is to add energy and diversity to “the issues” that are otherwise seen as colorblind. Invariably, when Black folks organize or try and make specific demands, they are seen as playing “Oppression Olympics” or being separatist. On the other hand, the unique modes of anti-black racism—especially slavery and jim crow—are mobilized as analogies to energize PoC/progressive movements around immigration, marriage equality, school reform, and whatever new social issue of the day.

If you didn’t know, let me tell you: Gay is not the new Black. Green is not the new Black. Poverty is not the new Black. As Q-tip from A Tribe Called Quest said, Black is Black. Using blackness, and in turn Black people, as a metaphor to forward agendas of nonblack constituencies only helps to solidify blackness as the archetype of suffering without understanding the inherent limits of that analogy. If being Black is the marker of the worst shit that can happen to you, a unique response is required. That is where the work of Red, Bike and Green may be exemplary for organizing.

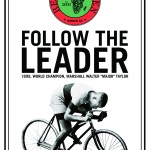

One of our shared goals on RBG rides is to make sure no one gets left behind while on a group ride. This may seem like a modest concept, but it has the ability to transform the people who participate. Our First Friday ride this season, we had three flat tires in a 10- to 12-mile bike ride. Before we could make the first right on the street we had left from, one of the riders caught a flat. And we stopped another two times to fix tires. To fix a tire requires basic bike mechanic skill, but perhaps more than that, it requires larger group communication and cooperation. Organically, the riders with the know-how to fix a flat commenced the operation: removing the tire, pumping up the spare, and then sliding it back on the wheel. In my three years with RBG, we have never had that many flat tires on one ride. This moment in the group ride highlighted our ability to maintain shared leadership and take care of each other, even though it meant that as a group, we wouldn’t be able to go as far and as fast. Since riding with RBG is not a race, we make sure that everyone who shows up is accounted for at the beginning and the end of each ride. And this is important because the presence of Black people is so often used as a commodity of progressiveness and equality, even when the interests of others in the group are just fine with leaving the interests of Black people behind. We are movement by, for, and about Black people.

Research has suggested that specificity toward one’s experiences is necessary regarding mental health and education (HBCUs). The call to create a space where there is common understanding, common language, and common feelings is one that I find grounding on a number of levels. In this sense, making an intentional practice to create intersubjective space relieves the need to code switch, represent in some fashion all of Black humanity, and explain your identity (e.g., why widespread police brutality is an everyday concern, why it is not okay to touch our hair without our permission). Come as you are. Leave your mask(s) at home or hang them up for decoration. But no matter what, be you.

The ethos of RBG is that our commonalities—being the prototypical targets of state violence— are not the impetus for charity but rather solidarity. I can’t stress enough, at least anecdotally, how many times people in West Oakland, North Oakland, or East Oakland have waved at us from their porches, smiled from bus stops, and honked their horns in celebration of seeing a bunch of Black folks on bikes. RBG is able to transform the space we inhabit because there is no pretense that Black bodies don’t produce a certain type of knowledge. I’m not saying it’s a utopia, but it damn near feels like a utopia. It’s a feeling…It’s a feeling.

_______________________________________________________

Juliana “Jewels” Smith is a cultural worker and an aspiring revolutionary. She earned her B.A. in Sociology from UC Riverside and M.A. in Ethnic Studies at UC San Diego. She is one of the core organizers of Red, Bike and Green, Oakland. She is also the creator and writer of (H)afrocentric: the Comic.

Juliana “Jewels” Smith is a cultural worker and an aspiring revolutionary. She earned her B.A. in Sociology from UC Riverside and M.A. in Ethnic Studies at UC San Diego. She is one of the core organizers of Red, Bike and Green, Oakland. She is also the creator and writer of (H)afrocentric: the Comic.

0 comments