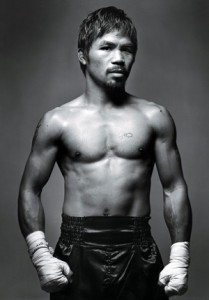

Reflections on Manny-gayte

By Theresa Runstedtler

I’ve been a fervent Pacquiao fan for many years but “Manny-gayte” has left me feeling uneasy about my loyalty to him in his upcoming fight against Tim Bradley.

I’ve been a fervent Pacquiao fan for many years but “Manny-gayte” has left me feeling uneasy about my loyalty to him in his upcoming fight against Tim Bradley.

Over the past few days, Twitter and Facebook have been all afire with reports of the Filipino boxer’s criticisms of President Barack Obama’s support of gay marriage. According to one report Pacman even quoted Leviticus 20:13, declaring that gays should be put to death. However that report turned out to be false. Whether or not Pacquiao actually said that gays should be put to death, it’s abundantly clear that he is a proponent of conservative Catholic doctrine on issues of homosexuality (and also birth control).

Pacquiao made a somewhat feeble attempt to clarify matters:

I’m not against gay people… I have a relative who is also gay. We can’t help it if they were born that way. What I’m critical of are actions that violate the word of God. I only gave out my opinion that same sex marriage is against the law of God.

His statement sounds a lot like something my mother would say,

Hate the sin, not the sinner.

Full disclosure: I’m Filipina (on my mother’s side; my father is Canadian) and I grew up in an über Catholic household where I learned that birth control and abortion were immoral and that homosexuality was a sinful lifestyle. I’ve had numerous, heated debates with my own mother about the calcified Catholic canon on sexuality. As far back as high school, I began pulling away from the church because of the Vatican’s stubborn refusal to acknowledge the rights of all people, its insistence on maintaining a patriarchal organization, and its failure to deal with the realities of HIV/AIDs and unplanned pregnancies. Of course, the child sexual abuse scandals involving priests have only strengthened my disappointment in my formal church.

Sometimes I wonder, is it possible to be a progressive Catholic? I would hope so, but I’m just not sure. To my mind, we should be more focused on the golden rule – “Do to others as you would have them do to you” – than on regulating other people’s bedroom activities.

As someone who also writes on the history of boxing and the sport’s central place in public discussions of race, gender, and imperialism at the turn of the twentieth century, I find it very ironic that a Filipino prizefighter has inserted himself into a discussion about homosexuality and marriage in the United States.

As someone who also writes on the history of boxing and the sport’s central place in public discussions of race, gender, and imperialism at the turn of the twentieth century, I find it very ironic that a Filipino prizefighter has inserted himself into a discussion about homosexuality and marriage in the United States.

In many respects, both Pacquiao’s chosen profession and his commitment to embodying a certain kind of heterosexual/patriarchal masculinity are, in part, indebted to the impact of U.S. colonialism in the Philippines. (Of course, the devout Catholicism can be traced back to Spanish colonial times.)

In the late 1890s and early 1900s, U.S. servicemen initially brought boxing to the archipelago as a mode of military discipline during the Philippine-American War and ensuing U.S. occupation. It was supposed to keep U.S. soldiers from “going native” in the tropics. Faced with high rates of desertion, suicide, venereal disease, and substance abuse among their troops, U.S. military officials promoted boxing. After all, boxers in training were supposed to avoid tobacco, alcohol, and sexual activity.

Boxing also became part of the United States’ overall program of “benevolent assimilation” or the efforts to use public education, English-language instruction, and Christianization to suppress indigenous cultures. In particular, U.S. officials saw Filipino men as feminine, childlike, and savage, and therefore unable to run their own country. Colonial authorities promoted boxing training as a solution to the supposed problem of Filipino manhood (or lack thereof).

Yet boxing took on alternative meanings for Filipinos, especially poor and working-class men. The ring became a place where they could publicly affirm their manliness and civilization in the midst of U.S. colonialism.

By the early 1920s, the Philippine legislature had passed a law legalizing boxing matches. Philippine universities began to introduce boxing into their sporting programs. There were calls for a physical revival:

The time when it was popular to be a top and dandy – when it was considered as a sign of good breeding to be able to show delicate and well manicured, effeminate hands – is past. One cannot be successful in life unless one is in constant ‘fighting trim’ (Pablo Anido, “Boxing in Manila,” The Ring, December 1923).

Boxing was a way for Filipino men to prove their virile manhood and proper patriarchy in the face of a U.S. colonial establishment that underscored their effeminacy and disputed their suitability for political self-determination.

In many ways, Pacquiao’s hard-line Catholicism and his desire to project a certain kind of Filipino masculinity comes out of this longer history. This, however, doesn’t make it okay, especially because Pacquiao is not only a pugilistic hero but also a politician and lawmaker in the Philippines. Here in North America we see so few depictions of strong and successful Filipino men in the mainstream media, so we crave public figures like Pacquiao. Yet, this shouldn’t have to come at the expense of the rights and needs of Filipina women and/or queer Filipino/as. I feel like Pacman has let us down.

Still Manny-gayte provides us with a teachable moment about the need to continue decolonizing our minds. Patriarchy, heterosexism, and U.S. expansion went hand-in-hand, and they have left a mark on what it means to be Asian Pacific in the twenty-first century.

____________________________

Theresa Runstedtler is Assistant Professor of American Studies at the University at Buffalo and, postdoctoral fellow at the University of Pennsylvania’s Penn Humanities Forum for the 2011-2012 academic year. She is the author of Jack Johnson, Rebel Sojourner: Boxing in the Shadow of the Global Color Line(University of California Press). Visit her blog at www.theresarunstedtler.com and follow her on twitter@klecticAcademik.

Theresa Runstedtler is Assistant Professor of American Studies at the University at Buffalo and, postdoctoral fellow at the University of Pennsylvania’s Penn Humanities Forum for the 2011-2012 academic year. She is the author of Jack Johnson, Rebel Sojourner: Boxing in the Shadow of the Global Color Line(University of California Press). Visit her blog at www.theresarunstedtler.com and follow her on twitter@klecticAcademik.

4 Comments