Still Mama's Baby–The Continued Relevance of the American Grammar Book: A Prologue

I have always been awful at football. And for that, I give thanks. The first thing I want to do is to thank my mother, Carole Elizabeth Benton Ricks, and my father, Alvin Antonio Ricks, for not letting me play football until junior high school and for never being particularly enthusiastic about my doing so. They were both Harlem kids transplanted by the thermals of the Great Society to the “new” New South, and because they were from Harlem, they could smell a hustle. And football, like other big sports, is one of the most vertically integrated hustles imaginable. This is really just to say that my parents could see the traces of capitalism working, turning its wheels about how to use young Black bodies like mine, turning young Black boys like me into the raw material of its avaricious pursuit for the almighty dollar, and all the while, working a kind of wicked magic on our souls–our very formation as subjects–in a way that bore more than passing resemblance to the auction block. In fact, I recall talking with my Mom and her sister about professional athletes as slaves when I was 17 years old. They asked me if the fact that professional football players make as much money as they do made any difference in my formulation. I said no. They said, “Hmm. That’s an interesting thought.” They didn’t disagree.

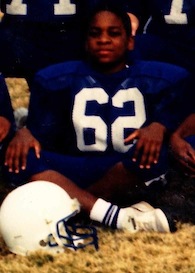

The author, Omar Ricks, in 8th grade, posing for team portrait. Also, warming up to sit on the bench.

By the time I did get into football, I wasn’t really into it. My heart was never really into hurting the other person across the line from me because I saw too much of myself in the eyes of that other person. My strength just didn’t flow there. I think this is because I had taken more time to know something that Hortense Spillers has called “the ‘female’ within” that African American men like me have the specific occasion to learn. But, and I must say this, I learned “the ‘female’ within” from my father every bit as much as I learned it from my mother. And I was lucky, lucky, lucky to have them both, because that sensitivity is the only way that I still know how to fight. I am glad that my parents redshirted me from the factory of the Black masculine neo-slave so that I had just a little more time–a very little more time–before I had to contend with its brutal, unpadded combine.

Indeed, I am haunted by the continued relevance of Spillers’ 1987 essay “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book” in my life and in the lives of Black men and women (transgender and cisgendered) whom I know. As our lives unfold, the Grammar becomes clearer, but the logic of that Grammar is always exceeded. The Grammar is antiblack violence–and specifically our availability to any kind of violence from anyone. It is what gives coherence to American life. It is the violence of the state, like the official execution of Troy Davis and the summary execution of Rekia Boyd, whom it kills with impunity, with little regard to their genders. It is the violence of civil society too, like George Zimmerman’s hunting and execution of Trayvon Martin. It is a grammar that gives order and coherence to the worlds in which we live every day. And it functions in the same way that grammar gives order and coherence to this very sentence.

But the excess of it is what exerts deep and formative effects. I celebrate the fact that I am as nonviolent a person as I am because my parents placed themselves in between my 12-year-old self and the football industrial-complex, reaching from its lofty heights into ever-younger ranks of Black boys. But the humanity of who I am–who all Black women and men, transgendered and cisgendered are–is also antagonistic toward the very forces that give us this access to different kinds of gender. In other words, the “effeminate” Black male style of cool that allows Michael Jackson and Walter Payton and Jimi Hendrix to electrify the world, the “masculine” Black female style of cool that allows Erykah Badu and Serena Williams and Nina Simone to pioneer whole new ways of being in the world — all of this, beautiful as it is, arises from the ongoing regimes of violence to which we were and are subjected–violence that is so excessive as to “ungender” us. Spillers’ work helps makes this clear. This American Grammar of violence is the reason why, as Spillers says, we Black men have access to the mother within.

If we give birth to pearls–if, indeed, we are the pearls to which we give birth–it is only due to the internal and external Sturm und Drang that converges on our bodies. That is the American Grammar that turned Trayvon Martin from a “sweet” boy into an unclaimed corpse in the morgue. The semiotics of violence are exceeded every day where our bodies are concerned, and the combined effects of this semiotics work to render the stability of gender categories among Black people very, very questionable. Here, a pregnant woman whom a Georgia police officer kicked in the belly so hard that she was forced to have an emergency C-Section. There, an elderly man whose “LifeAid” button ends up being what kills him, by way of the White Plains (NY) Police Department. Here, a transgendered woman who faces years in prison for defending herself and her friends on the racially hostile streets of Minneapolis. There, a cisgendered woman in Jacksonville, Fla., whose attempt to defend herself and her children from her abusive husband gets her 20 years in prison. Here, a young man whose attempt to defend his home from what he thought were burglars gets him three bullets in the chest, courtesy of Anaheim Police–right near the “happiest place on earth.” There, an elderly woman whose attempt to defend her home from what she thought were burglars gets her killed and framed posthumously for drug possession courtesy of the Atlanta Police. Here, a heterosexual inmate in California whose repeated rape over multiple days is arranged by prison officials as “punishment.” There, a young woman whose attempt to get medical help in the hospital lands her in a St. Louis jail cell where she spends her last moments screaming and writhing in pain on the floor from the thing for which the doctors were sworn to treat her.

And those are simply the most graphic and spectacular cases of the antiblack violence that make up the specific parts of speech of this American Grammar. What about the fact that Black people routinely have twice the unemployment rate of white people and work in the most fucked up aspects of the jobs that we do get? Do we get to count that as violence? Or the fact that schools seem more concerned with confining our children than with giving them a good education? Or the fact that our “success” within the American paradigm–like the current Black president or Idaho’s first Black state representative–opens us to new forms of violence from all quarters, even from those who think themselves our allies?

And doesn’t that affect the ways that Black subjects are formed? In other words, don’t these supposedly isolated things coalesce into a larger meaning of Black life that exceeds the sum of its parts? How can we know ourselves as citizens, as football players, as voters, as subjects–let alone as gendered beings–when at every turn, we are faced with forces whose greatest acknowledgment of our gender is the size of the prison uniforms, or caskets, it has prepared for us?

For most of my life, I did not have these words. The Grammar wrung them from me. And there is still a lot that remains unsaid. I’m not even sure that Spillers says or would agree with all or even half of the stuff I’ve said above. All I am really trying to say is that I am grateful that Hortense Spillers wrote that essay, twenty-five years ago this summer. The essay gives pause the way my parents struggled mightily to give me pause before I got sucked into the antiblack subject forming machine of football. The essay forces one to think and mature and to slip into the space of hardened but sensitive listening, what some might think of as the oh-so-frangible air bubble of social life within our cauldron of social death. Out of whatever pain it took to say it like Spillers said it comes the only hope worth having: the end of the world. On this Mother’s Day, I am thankful for that monstrous possibility.

0 comments