Black Feminism and Black Moses, Part I

W. E. B. Du Bois’s poignant words in The Souls of Black Folk (1903), “The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color-line,” is scripture for Black folk in America. Citizenry after three centuries-plus of bondage ain’t been no crystal staircase. Black folks have navigated feral and diabolical racialized hostility since European contact, invasion, occupation, conquest, and colonization. To be clear, the systemic violence of theft of bodies, culture, identities, and histories; foreign rule; forced African dispersal; the trans-Atlantic slave trade; and the European scramble for African territory, caused not only alienation between people, land, and culture, but laid claim to the spirit of African diasporic being, identity, independence, and thriving.

Today, when we think of the slave trade in America, many think of a system long gone that ended over a century and half ago. We think of [often a watered-down version of] what was, not what yet still is. We think of the magical Civil War that ended slavery and gave everyone shared access to the American Dream, not the reality that the same demonic colonial tools, political structure, and economic system that captured, enslaved, and traded an estimated 12 million Africans from Central and West Africa between the 15th and 19th centuries to be “slaves for life,” along with any offspring, still exists. Many of us are the offspring of Africans interpreted not as humans, but legal property aka cargo aka merchandise and sold to people who owned cocoa, cotton, coffee, tobacco, and sugar plantations. We are the descendants of domestics and field hands whose bylines, last names, diaries, testimonies, secrets, and seared flesh serve as reminders of our unique connection – to each other, land, experience, and the color-line. As Aimé Césaire reminds us in Discourse on Colonialism (1950), the dehumanizing, poisonous, and barbaric nature of coloniality, was distilled into the veins of our society. While we no longer live in a colonial context and “the official apparatus may have been removed…the political, economic, and cultural links established by colonial domination still remain.”

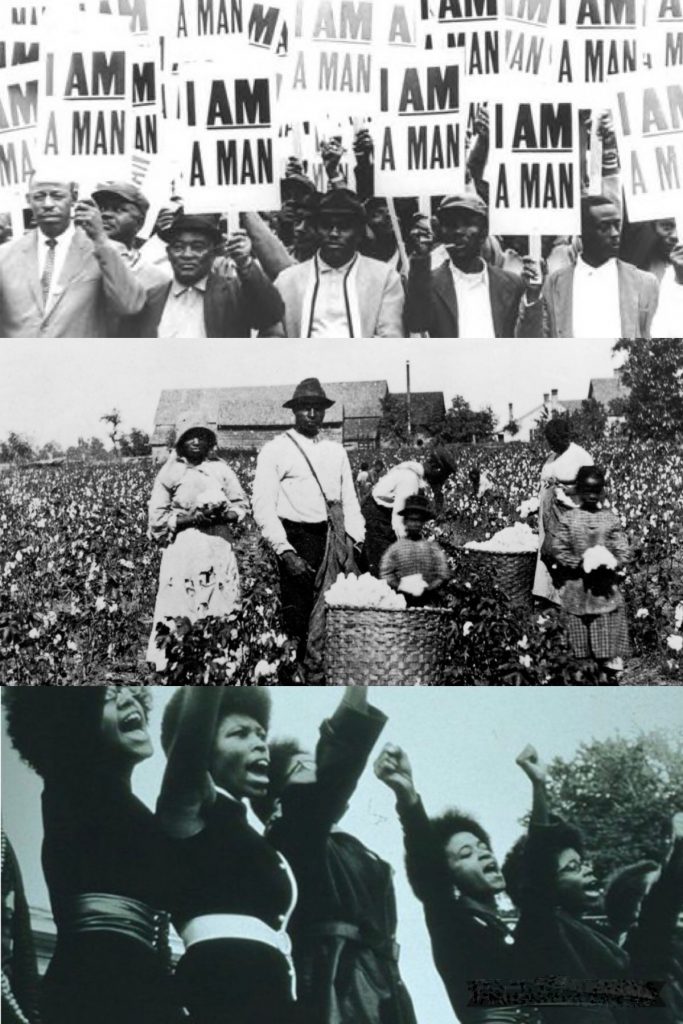

America is replete with colonial artifacts. Policing, mass incarceration, Black death, immigration laws, the juridical system, and the maintenance of socioeconomic class lines tell us this much. Neocoloniality is evidenced in and through a number of social hierarchies and forms of power and control intended to strip the Black diaspora of any semblance of freedom, justice, humanity, equity, or citizenship. And it means to stifle not only our liberation but our image. The collective battle for political freedom and from representational fabrication as darkness, evil, monsters, criminal, immoral, lazy, hyper-sexual, and so on, is real. The quest to be seen as ends rather than exploitable means to an end is real. And in the unyielding face of forced labor, joblessness, intimidation, police brutality, taxation, racial terror, theft, rape, incarceration, and murder, the 1960s signage and what came to represent the collective call of the social movement for humanity, “I Am A Man,” still rings true. In many ways, “I Am A Man” became a sublimation and lynchpin for naming Black oppression beneath the veil of the color-line.

The problem of the color-line impacts the African diaspora everywhere, forging a sense of collective fugitivity, multi-consciousness, and Black protectionism. Black folks are forever faced with questions and anxieties around belonging, place, personhood, and community. It’s only normal, and particularly in America, to protect the race for dear life. In many instances, “we’re all we got.” Simultaneously, it’s these realities and entanglements that shape Black desire for Black Moses – that magical genius warrior who will eventually and heroically save the Black diaspora in America: men, women, and children, and in that order. Antebellum Black radical resistance, the Black Reconstruction, and the Harlem Renaissance and the Black Arts movement taught us that Black radical power, opposition, genius, and creativity came through many identities, persons, expressions, and cultural forms, with each revealing a range of collective needs and responses to interlocking oppressions. However, it seems the Jim Crow era ushered in a particular love affair with Black Moses, the revolutionary Black male figure and leader of the race making real political moves via speeches, marches, organizing, and direct attacks on American politics.

Such a figure stands for Black manhood without apology and subsequently represents Black power, citizenry, humanity, and liberation. The merging between the quest for Black manhood and Black power, citizenship, humanity, and liberation is more than I can get into here. The short of it is, heteropatriarchy is a pillar of American empire, which equates manhood to the state, state power, and “natural rights,” and naturalizes the quest for male domination as a natural moral order (within the nation-state, institutions, local communities, and interpersonally) and the dominion of male needs as symbolic of power, liberation, and the well-being of the collective. True enough, Harriet Tubman was also referred to as Black Moses. Race, sex, and gender politics were more fluid during slavery. Post-slavery demanded a special place and role for an appropriation of Black patriarchy in Black families, communities, and institutions. Black Moses became symbolic for a particular kind of Black male leadership and such leadership became emblematic of Black power, progress, liberation, and thus what it meant to be free, powerful, human, and whole.

Black Moses, the liberator and exemplar of Blackness, fights on our behalf against the color-line and stubborn colonial artifacts such as the remains of Dixie, unregulated violence, white power structures, second-class citizenship, et al. And because of this he exists in somewhat of a protected Black class. Because he’s working on our behalf. Because he does good in the community. Because he’s fighting for social structures and programs needed for Black liberation. Because he understands not only the color-line but the transnational plight of the Black diaspora to be linked. Because as the saying goes, none of us are free until we are all free. However, given the history and context of race and racial oppression, many of us refuse to see or challenge the blind spots. We give in to racial solidarity and Black protectionism due to our shared place and history, and many of us do so at our own expense.

Du Bois was right. The problem of the 20th– and 21st– century is the color-line. But as Black feminists have been saying forever, it’s the intersections where race, class, sex, gender, and sexuality meet, too. Contrary to popular belief, Black feminism isn’t the enemy of collective Black liberation or Black men, families, and communities. Black feminism is an inclusive critical system of beliefs, politics, discourse, and social movement aimed at saving our collective Black lives and ending racist, sexist, heterosexist, trans-antagonistic, classist, imperialist, and capitalist exploitation and oppression. Black women and girls take up special space as both Black and women, and for some of us, as both advocates of Black life and women’s rights, we carry the burden of both the color-line and the gender-line on our shoulders. And we are more often than not pressured to choose one over the other; to note one as more oppressive than the other; to claim one as more or less significant; to prove our racial allegiance – through our lives, activism, servitude, third-classness, and too often our silence. But some of us carry signs fighting white supremacy, damning the history of slavery, collective racial oppression, rape, and breeding while concealing and swallowing down both interracial intracommunal violences. We are not supposed to talk about the latter…because the color-line is the Black problem…because white supremacy…because whatever our intracommunal experiences white men did it first and worse. And we surely aren’t supposed to say anything bad about Black Moses or his kinfolk in our communities.

Unchecked racial allegiance ain’t never liberated nobody. Black feminists understand the history of Black diasporic theft and oppression and how it’s operating in the contemporary moment as much as anyone. We understand neocoloniality got us collectively $%^&#@ up. We are not unaware. And we certainly aren’t working on behalf of white supremacy, as some like to argue – because in the words of Patricia Hill Collins, some see gender equality with Black women as defeat, disempowerment, and lack of entitlement. But some of us are of the Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, Anna Julia Cooper, Ella Baker, Angela Davis, Toni Cade Bambara, Michele Wallace, Combahee River Collective ilk. Black women’s critiques of the Black Moses model pivotal to the Black nuclear family/political project and paradigmatic for Black communal, social, political, and religious leadership ain’t nothin new. Believe it or not, there’s a way to hold our collective history, good works, and bad ideology and deeds in tension. That is, we can critique white supremacy, show racial unity, appreciate Black radical efforts towards progress, and hold our folks accountable at the same time. More, there’s simply no way to talk about ancient civilization, colonization, North American enslavement, and 20th and 21st century oppression and social movements without also talking about the experiences, roles, and histories of Black diasporic women – good and bad. Simultaneously, we cannot ignore how our quest for humanity and ultimately Black Moses, led and continues to lead to intracommunal heteropatriarchal sexism, homophobia, and trans-antagonism.

The color-line is real but Black Moses and Black protectionism won’t save us. Truth, Cooper, and Baker been told us this model won’t liberate us. Check out the speeches “Woman’s Rights” and “When Woman Gets Her Rights Man Will Be Right”), the essay, “The Status of Woman in America,” and the documentary Fundi: The Ella Baker Story (1981). Sometimes Black Moses righteously and powerfully advocates for Black pride, power, independence, and socio-political-economic unionizing while partaking in intracommunal oppression. This can’t go unchecked. The idea that intracommunal criticism halts Black liberative efforts is a lie. We have to start critiquing problematic ideals, models, paradigms, and folk in our communities, even when they’ve done a lot of good (or made good music…like R. Kelly or made us shout and raise our hands…like James Cleveland). Criticism is not only an act of love but self-care and intracommunal preservation. And if we can be honest, the demand for intracommunal silence around sex, gender, and sexual oppression in the name of racial solidarity is really for Black cisgender heterosexual men – because Black folk have no problem critiquing Black women and Black lgbtqia people. Because if Tubman were alive today, we’d be hearing all kinds of criticisms about her politics, her leadership style, her gender identity and performance, her looks, how she talks to Black men, her sex life, her multiple husbands, her single motherhood, and so on.

Somebody send this article to Tamika Mallory, leader of the Women’s March currently facing harsh criticism for refusing to distance herself from Minister Louis Farrakhan. Sis is out here carrying the burden of the color-line and its centrality in Black struggle and the Black liberation tradition, neocoloniality, Black Moses, the quest for Black identity and it’s coiling with aspirational patriarchal Black manhood, and Black feminism along with it’s fundamental intersections between race, class, sex, and gender all on her shoulders. Yet while fighting for women’s rights and against white racism, including liberal white women’s racial allegiances, racial exclusions, and antiblackness in social movements, which Black feminists have been calling out since forever (see Sojourner Truth and here and here and here and here or just google “black feminist syllabi”), she’s seesawing her way between her allegiances to Black feminist politics and Black Moses. And she is neither the first nor the last to find themselves between the hard rock of Black feminism and the hard place of Black protectionism. It’s hard out here for Black feminists. Our racial history sometimes demands allegiances to people who’ve said or done harmful things. Thus some of us practice feminist politics while protecting our heteropatriarchal friends. Truth is, they are often people we love and are in community with. Sometimes we look up to them. And if we can keep it all the way real, sometimes we appreciate and find value in them — in Black Moses, Black male power, and yes, even Black male domination for some. Sometimes we actually do think that when Black men get their rights everything else will be alright.

Not that Mallory believes any of this. Admittedly, we’ve never met or spoken. But there is an especially nuanced and complex road that she’s traveling as a Black woman activist being called to stand against white racism and sexism, on one hand, and against a powerful Black Moses by white media, on the other. It’s easy to do the former. It’s easy to forcefully and unambiguously name white supremacy and to call out white, white passing, and non-Black women. It’s easy to denounce the color-line and neocoloniality that shapes our lives. The hard part is standing with and for Black men (and women) while also just as explicitly holding them accountable. And I don’t think Mallory does this with regard to Farrakhan. While she is expressly clear that she doesn’t agree with Farrakhan (and here) on all things, Black feminism calls for a more layered and nuanced response, not a rhetorical tap dance. We know she disagrees with his statements on anti-Semitism, sexism, and homophobia. However, the repetitive and rehearsed response, “I don’t agree with these statements,” is not enough. “I don’t agree” or “I critique systems and structures, not people” is a cheap way of refusing to offer a necessary critique, which Mallory is most certainly capable of doing when it comes to white supremacy. But again this is tricky terrain.

Before I’m accused of working for white supremacy let me say this: I applaud Mallory for refusing to dispose of Farrakhan.

She’s not the first to be asked. White Americans have been demanding Black activists to dispose of him in order to access allying and resources and to perform proper and acceptable Blackness for decades. And Farrakhan is not the first. Divide and conquer is an age old tool. That said, while Black folks love our Black Moses’s, the media and political powers that be hates them. Thus, after reading about the DNC’s move to distance itself from the Women’s March and watching Mallory on The View, I wrote the following,

While I get the critical space black women activists take up as both black and women, and more, as both advocates of black life and women’s rights, I feel like Mallory should own her loyalty to Farrakhan. She doesn’t need to disown him (dis/owning is a white supremacist antiblack project – I prefer critique and accountability). But she does need to be more forthright about why she’s not. And more, about why she sees him as the GOAT. She should own that race may possibly trump all else in her radical politics. And she should own that she wasn’t likely thinking about his other harmful positions, including those on Mike Tyson, R. Kelly, and rape culture, when uplifting his racial politics. However, as a black feminist, I’m troubled that he’s even in the middle of this, getting all of this airtime, and that she’s yet holding onto him with the whole “I go wherever my people are…including prisons.” That analogy was interesting, to say the least. But also, it felt grossly disingenuous. It would be great if she worked through these nuances and perhaps excused herself from the march while doing so (so that she doesn’t cause further harm). She can always come back and/or work behind the scenes. In the meantime, I continue to side-eye **any** black feminist refusing to call Farrakhan out on, at minimum, his sex and gender politics. I recently re/listened to the recording of him included in NO! The Rape Documentary, by Aishah Shahidah Simmons, where he talks about Mike Tyson’s rape charge, and I was sickened to my stomach.

I went on to comment,

I really want her to critique Farrakhan AND white media for requesting that she and black folk in general dis/own radical black voices. I find their outrage disingenuous as well.

I applaud Mallory for her refusal to dis/own, not for her refusal to offer radical critique on a mass-mediated platform. I applaud her for naming white supremacy and white privilege and for making lucidly clear the systemic, structural, institutional, and interpersonal violences of the color-line. I applaud her for balancing the history of womanhood and contact, conquest, and colonization. And I even applaud her for wanting to protect Black Moses, given all he represents to Black communities both figuratively and realistically. Such protectionism feels like protecting the race and standing boldly and in solidarity in the face of racist politics and media. It feels like a win for Black humanity and liberation and especially for Black men – and particularly as Black manhood and Black Moses have come to equate to each. And while I understand what reads as contradictions between Farrakhan’s anti-Semitism and Mallory’s radical vision of freedom for all people from all oppressions, I won’t get into that here. There is a complex relationship between Jewish people, whiteness, white passing folks, and Black folks. Let’s just say, the trans-Atlantic slave trade, diasporic dispersal, the scramble for Africa, antiblackness throughout the Americas, and the quest for whiteness didn’t yield us any friends. The Portuguese, the British, the French, the Spanish, the Dutch, the Caribbean, and those others occupying the western empire were all happy to engage in New World trading and the oppression of humans. And those groups later given access to whiteness in the New World, despite their own oppressions, have been equally happy to partake in the structures and fruits of antiblackness. That said, it’s a tangled web that needs more space and time.

But what of Farrakhan’s previous statements about rape? What of how he claims to hate rape and rapists, on one hand, while calling survivors liars and dabbling in rape culture and rape jokes, on the other? What of how he explicitly stands against rape, and especially white male rapists, the raping of young boys in the Catholic Church, and the rape of Black women by white enslavers but when he discusses Black men like Mike Tyson and R. Kelly he moves towards discourses on forgiveness, genius, the divinity within, and how all have sinned (grace clearly reserved for Black men)? What of how he exclaims women are sacred and to be honored and jezebels who lie in the same breath? In a 1992 speech on Tyson he said the following:

You bring a hawk into the chicken yard and wonder why the chicken got eaten up. You bring Mike to a beauty contest and all these fine foxes just parading in front of Mike. Mike’s eyes begin to dance like a hungry man looking at a Wendy’s beef burger or something. She said “no Mike no.” I mean how many times, sisters, have you said “No” and you mean “Yes” all of the time. Wait, wait, I’m talking to the women. We’re going to talk now. You see, the days of the bs (bull shit) is all over. You’re not dealing with a man that don’t know you and the damn deceitful games that you play” (Transcript of NO! by Aishah Shahidah Simmons) (You can listen to the rest of the speech here: 1:47:00-2:14:06)

Does this not require precise Black feminist righteous rage? I encourage readers to listen to the video and sit with the male approval and laughter in the audience. We can’t be out here calling Black Moses the GOAT and not naming this – not as Black feminists. Our politics necessitate at least a nuanced word or two. Rape apology, especially when it comes to Black women, is anti-Black-feminist.

This is the game of double-dutch Black feminists are forced to play and have long played. We understand the force of neocoloniality and systemic and structural racism. We know the impact it’s had on Black communities and Black men. But we also know the inter- and intracommunal effects on our lives as well. Here’s the thing: It’s okay to appreciate and stand up for racial contributions while offering a critique of harm. This is not about telling Mallory what to say, a critique she’s made when pushed to offer a more unambiguous critique of Farrakhan – a critique that means to absolve her of providing said criticism. This is about the reality that patriarchy, sex, gender, and sexual oppression and violences are colonial artifacts, too, and how Black feminist politics and leadership demands we foreground not only the history and operation of the color-line but also how sex, sexual, gender, and class oppressions systematically shapes, limits, and denies our existence and thriving – regardless of the source, including our very own Black Moses. Especially, Black Moses.

As I watched Mallory forcefully and dynamically grace the airwaves last week, I grew frustrated where it seemed everyone else was applauding. I understood her unapologetic Blackness, Black feminism, and Black protectionism, well. I understood her love for the NOI and Black Moses. More, I understood our collective applause and how our systemic oppression and desires for not only racial unity and power but a Black Moses shaped it. At the same time, I recalled all the times that racial unity, while necessary and potentially liberating, called for our silence and third-classness, how resisting colonial artifacts meant protecting Black Moses at all cost, and how such protectionism meant also excusing intracommunal trauma. Black feminists can’t stand for Black life and Black inflicted trauma. Despite all of his good in Black communities, Farrakhan is on record supporting Black sexual and gender terrorists, rape culture, sexism, patriarchy, homophobia, and trans-antagonism. And no, it’s not enough to simply say we don’t agree with everything Farrakhan says. We can unequivocally note white terror and Black intracommunal oppression at the same time. Concomitantly, we can aspire to radical racial solidarity and accountability concurrently.

But be clear: this is bigger than Farrakhan. Farrakhan is a Black Moses figure, not the Black Moses figurehead. There have been many. The bottom line is this: the problem of the 21st century is still the color-line. However, the color-line is irreducible to equal access to cisgender heteropatriarchal Black manhood, ideas, needs, and accomplishments, and Black oppression can’t be totalized by the color-line. More, Black Moses devoid of Black radical inclusive politics, love, and a vision of intersectional Black diasporic liberative ethics, is ineffectual. And finally, Black Moses must be called out on his ish. Ultimately, we don’t need a cisgender heterosexual or singular Black Moses paradigm. Ella Baker explicitly warned against this. We need collective leadership inclusive of those from the furthest edges of the social margins who are willing to fight against the force of entwining Black oppressions. This doesn’t mean we don’t love and value cisgender heterosexual Black male leaders. Absolutely, we do. It means Black leadership must always be accountable to ALL Black people and as inclusive as our Black lives.

The problem of the 21st century are our interlocking Black oppressions.

About the author…

Tamura Lomax received her Ph.D. from Vanderbilt University in Religion where she specialized in Black Religion and Black Diaspora Studies and developed expertise in Women, Gender and Sexuality Studies and Black British and U.S. Black Cultural Studies. In 2018, Dr. Lomax published her first single authored monograph, Jezebel Unhinged: Loosing the Black Female Body in Religion and Culture (Duke University Press). She also organized and guest edited the special issue, “Black Bodies in Ecstasy: Black Women, the Black Church, and the Politics of Pleasure” (Black Theology: An International Journal, Nov 2018). In 2017, Dr. Lomax curated #BlackSkinWhiteSin, a discourse on sex, violence, and the Black Church. In 2014, she published Womanist and Black Feminist Responses to Tyler Perry’s Cultural Productions(Palgrave Macmillan), a co-authored edited volume with Rhon S. Manigault-Bryant and Carol B. Duncan. She is currently at work on her latest book, Raising Non-Toxic Sons in White Supremacist America. She is the co-founder, CEO, and visionary of The Feminist Wire. For more or to conact, visit Bios.

0 comments