Self-Determination and the Struggle to End Violence Against Women Living with HIV

By Keiko Lane, MFT

I don’t think we had slept together yet when he told me about the pills. He was, well, not exactly hoarding them, it was more intentional than that. He was collecting them. Counting them. There was a plan.

I don’t think we had slept together yet when he told me about the pills. He was, well, not exactly hoarding them, it was more intentional than that. He was collecting them. Counting them. There was a plan.

He was one of my best friends, a dearly beloved fag from my Queer Nation and ACT UP chosen family. HIV+ for years before we met, his health was uneven. Some weeks he felt pretty good, and we’d spend evenings at meetings of ACT UP’s People of Color Caucus. Days were often spent at the hospital visiting friends who were having bad weeks. Sometimes when he had a bad week I’d curl into his hospital bed with him. His jaw always hurt from clenching against pain in his sleep. Sometimes, if I used my thumbs to rub his jaw right at the joint, he’d stop grinding without waking up.

Once we did sleep together, it wasn’t what you might guess. Sometimes, after an especially difficult hospital visit, lines would get blurry. Maybe it’s exactly what you’d guess. It’s a cliché, isn’t it? Sex as antidote to death. But it wasn’t an antidote. Just warding off the aloneness for as long as we could.

He wasn’t the only one who collected pills. We didn’t talk about it much, but all of them—friends and lovers who were HIV+—watched each other’s decisions and struggles toward the end. Then at the exact end.

We didn’t have a lot of choices in the early 1990s.

We avoided beginnings of life. Pregnancies were dodged even when we had fantasies of children—fantasies of generational memory moving forward—because pregnancies meant exposure to HIV. This was before PrEP, before TasP, before the cocktail, and before people started surviving. We learned how to do end of life, but there weren’t any good options for a beginning of life that wouldn’t put us all at risk and ensured that we would be around to raise those could-be children.

Planned Parenthood became my regular HIV testing site. My family doctor couldn’t reconcile the image she had of me as a high-achieving Asian American young femme, with her stereotype of someone at risk of HIV exposure. The AIDS and LGBT community organizations that offered free and anonymous testing then weren’t used to dealing with queer women who were at risk. Test counselors were almost always gay men, most of whom didn’t know much about women’s sexual health. Planned Parenthood was easier; test counselors didn’t blink. They ran full STI panels, asked if I wanted birth control other than condoms, handed me a stack of condoms, and sent me on my way. Nurses handed me envelopes of latex gloves to fit my small hands.

Somehow I remained HIV negative. Many of my friends didn’t. The conversations about pills and endings happened over and over. So did the conversations about how we form families and how we take care of one another.

SEROCOMPLICATED

Now, in my psychotherapy practice my clients, many of whom are HIV+, are having those same conversations with their loved ones. So much of the landscape has changed. There are more distinctions and categories than just seropositive and seronegative. Many of my clients are “serocomplicated.” They have viral loads that are mostly suppressed but sometimes spike, usually during times of great stress.

What hasn’t changed much are stressors—the traumas of daily life—so insidious that people often forget to think of them as forms of violence: The difficulty accessing safe and affordable health care; the increasing difficulty of accessing safe and affordable housing; police targeting and violence; the murder and assassination of trans women of color; the dismal rates of intimate partner violence experienced by women living with HIV, be they heterosexual or queer, transwomen or ciswomen; the criminalization of people living with HIV; and the impact of stigma on the mental and physical health of individuals and families. In 25 years, some things have not gotten better.

ENDING THE VIOLENCE

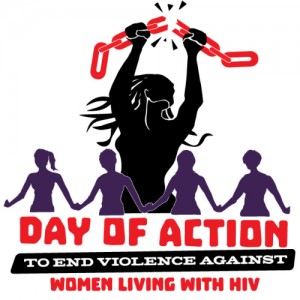

Today, is the Day of Action to End Violence Against Women Living with HIV. One of the issues the Positive Women’s Network will address is the magnified rate of intimate partner violence experienced by women living with HIV.

Nationally, one out of three women will experience violence or abuse at the hands of a partner at some point in her life. The number rises to one out of two among women living with HIV, and three out of four when other types of abuse are included.

SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Heath Collective defines reproductive justice as:

The complete physical, mental, spiritual, political, economic, and social well-being of women and girls, and will be achieved when women and girls have the economic, social and political power and resources to make healthy decisions about our bodies, sexuality and reproduction for ourselves, our families and our communities in all areas of our lives.

For women living with HIV—heterosexual and queer, cisgender and trans—the definition of reproductive justice is the same: the ability to make choices throughout the lifespan about bodily and familial self-determination free from violence or the threat of violence.

In the past few weeks, many of my clients have been talking about Planned Parenthood. For them, as it was for me years ago, it’s their STI and HIV testing center. And, because some things have changed, Planned Parenthood is a place where transwomen as well as ciswomen can go for fertility information, to access PrEP for family planning with positive partners, and to discuss TasP in service of forming families with seronegative partners.

Planned Parenthood is also where many of my young male clients go for their healthcare. And when I say male, I mean identified. Young cis gay men go there for HIV testing, PrEP, and HIV treatment. And young transmen go for pelvic exams, PrEP, HIV, and pregnancy tests.

Reproductive justice is HIV justice. Cutting off access to necessary and lifesaving services is a form of violence. The attempts at defunding Planned Parenthood are an assault against the communities in which I participate and where I have alliances.

Violence is explicit.

And violence is implicit.

LIFE SPAN AND DEATH

At work, I might spend an hour with a client talking about family planning. I might spend the next hour talking with someone else about how they want the end of their life to look. In HIV-impacted communities, death often exists side by side with fantasies of the future.

Two bills recently signed by California Gov. Jerry Brown address both of those life span markers. AB960, the Equal Protection for All Families Act, protects intended parents of all genders and chosen relationships in the conception and birth process. ABX2 15, California’s Death with Dignity Act, allows people to have more agency and decision-making about how they want their lives to end.

None of these bills, as important as they are in the struggle for self-determination and agency, as long as there is inequity in the social and political construction of power, and as long as some lives matter more than others, will be enough. I see it in lived out in the bodies of my clients. When violence is systemic and insidious, and self-determination is a constant struggle, whose nervous systems get to recover? And when nervous systems are overtaxed, getting a viral load to undetectable gets harder and harder.

I listen daily to the experiences of HIV + women in my life. I think about the complexity of change in last 25 years, and the almost 20 since my friend took his last pills. What has changed? What has stayed the same? How do we stay in alliance with one another?

Complex trauma isn’t only intimate partner violence. It’s understanding the context of a world that would seek to destroy us. The politics of women’s healthcare puts women in a standoff with an abusive system—one of intimate contact from which it is impossible to escape. Keeping trauma informed care at the center of my work with my clients means understanding the individual, bodily, micro level of their lived experience as well as the policy and organizational macro experiences of that impact their lives. It means grieving the lack of a world where they can live out the social and political power and resources to make uncoerced choices about their bodies, sexuality, reproduction, and family making, and then fighting to make that world.

So much of what I know about what it means to chose a family, how to take care of one another for the full course of a life span, I’ve learned from the HIV+ women and men in my life, those who have survived and those who have not. When I sit with my clients who are seropositive and serocomplicated, we remember together what they wanted for themselves before their diagnosis and how we can make a life and a world in which they can have it still. And I remember what my friend wanted at the end—and they are really the same things—dignity and self-determination. The ability to chose who to love and how to make families without fear. Together we work to make it true.

Keiko Lane is a Japanese American psychotherapist, writer, educator, and activist. In addition to her literary writing, which has been published in journals and anthologies, she also writes about the intersections of queer culture, oppression

resistance, racial and gender justice, HIV criminalization, reproductive justice, and liberation psychology. She has a private psychotherapy practice in Berkeley, CA specializing in work with queers of all genders, artists, activists, academics, asylum seekers and other clients self-identified as post-colonial. Keiko also teaches graduate and post-graduate psychotherapy courses on queer and multicultural

psychotherapies, the psychodynamics of social justice, and the embodied literature of exile. www.keikolanemft.com

0 comments