Straight Outta Rape Culture

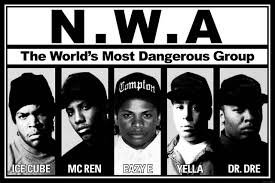

When N.W.A.’s mega-hyped biopic Straight Outta Compton opens this Friday, the brutalized bodies of black women will be lost in the predictable stampede of media accolades. While early reviews have lauded the “prescience” of the group’s fierce critique of anti-black state violence and criminalization—epitomized by its de facto theme song “F– Tha Police”—they fail to highlight how the group’s multi-million dollar empire was built on black women’s backs.

Yet, as national outrage over state violence grows, the release of the film should prompt fresh reconsideration of how institutionalized sexual and intimate partner violence against black women continues to be all but invisible in mainstream discourse about black self-determination. As gangsta rap pioneers and beneficiaries of the corporatization of rap/hip hop in the 1990s, N.W.A. played a key role in yoking rape culture and rap misogyny. Throughout their career they’ve been hailed as street poets and raw truth tellers mining the psychic space of young urban black masculinity. In song after song, gang rape, statutory rape, the coercion of women into prostitution and the terroristic murder of prostitutes are chronicled, glorified and paid homage to as just part of the spoils of “ghetto” life. The 1988 song “Straight Outta Compton” trivializes the murder of a neighborhood girl (“So what about the bitch that got shot, fuck her, you think I give a damn about a bitch, I’m not a sucker”) while its outlaw male protagonists go on an AK-47 and testosterone fueled killing spree. “Straight Outta Compton” was an early salvo for such popular fare as “To Kill a Hooker,” “Findum, Fuckum & Flee” and the rape epic “One Less Bitch” in which N.W.A. co-founder Dr. Dre lets his boys gang rape a prostitute then notes, “the bitch tried to ‘gank’ me so I had to kill her”.

In a recent L.A. Times profile on the group, writer Lorraine Ali extols Dr. Dre’s role as a businessman and entrepreneur while conspicuously omitting his history of vicious misogyny and violence against black women. Sidestepping the importance of misogynoir to the group’s body of work, Ali argues that “it’s the film’s depiction of police brutality, and the tense dynamic between law enforcement and the urban neighborhoods they patrol, that makes it so topical”. Ali’s near reverent profile of the group is yet another example of white America’s double standards when it comes to the brutalization of white women versus that of black women.

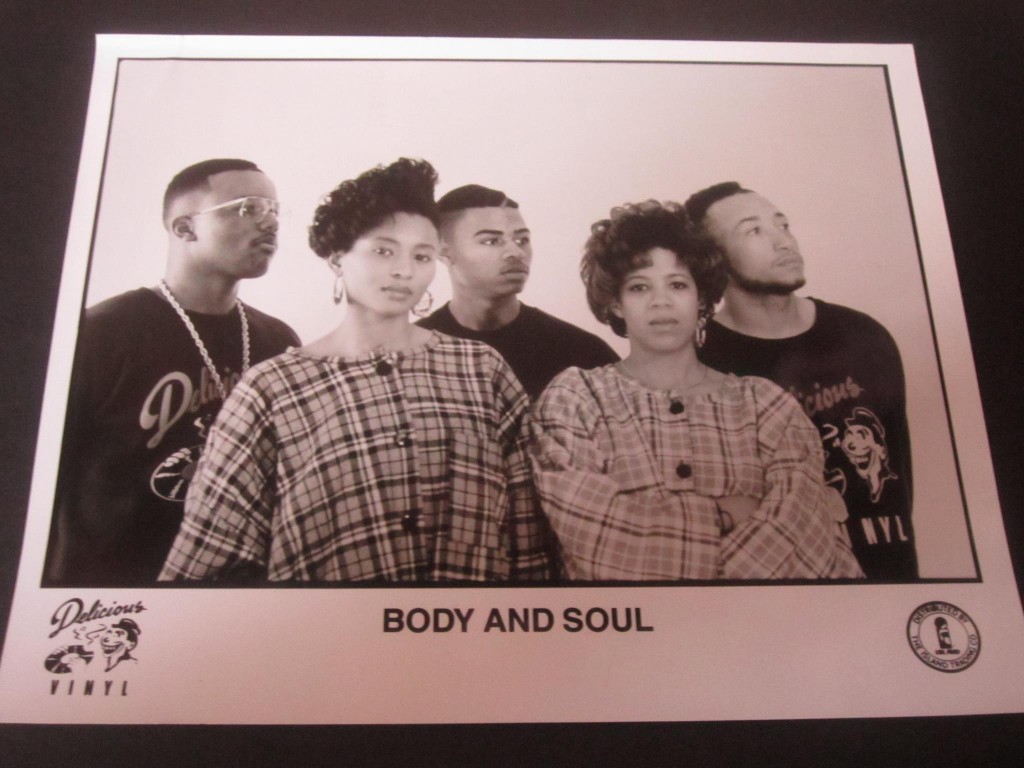

In 1991 Dre brutally beat and trashed Dee Barnes, the young African American host of the forerunning rap show Pump It Up, at a record release party in Hollywood. Allegedly spurred by negative comments made about the group on the show, Barnes’ beating was co-signed by N.W.A. members Eazy E and MC Ren. Pump It Up was one of the first grassroots showcases to capture the hip hop juggernaut in its infancy. Barnes, a talented rap artist in her own right, was in a group called Body and Soul with my cousin Rose Hutchinson, another pioneering female rapper. The assault by Dre all but ended her rap career, underscoring black women’s perilous status in the rap/hip hop world as well as the obscene rates of intimate partner violence in the African American community overall (it is worth noting that Barnes was not the only black woman to suffer a brutal attack at Dre’s hands. Dre’s ex-girlfriend, rapper Michel’le, alleged that she needed plastic surgery after she was beaten by him).

Every year thousands of black women are shot, stabbed, stalked, brutalized and sexually assaulted in crimes that never make it on the national radar. Black women experience intimate partner violence at a rate of 35% higher than do white women According to the Department of Justice nearly 40% of young black women have experienced sexual assault by the age of 18. Further, in Los Angeles County black girls have the highest rates of domestic sex trafficking victimization and are more likely to be locked up for prostitution than non-black women.

And although intimate partner violence is a leading cause of death for black women, they are seldom viewed as proper victims and are rarely cast as innocents. Far too often, intimate partner violence (such as that committed by former NFL player Ray Rice against wife Janae Rice) and/or sexual assault against black women are only propelled to national attention by a perfect storm of graphic videotape and feminist of color outrage. Yet black female survivors suffer on the margins in a culture that still essentially deems them “unrapeable”.

As an educator and mentor I work daily with young black girls who silently cope with the trauma and PTSD of sexual and physical violence in the very same South Los Angeles communities “immortalized” in N.W.A.’s hyper-masculinist terroristically sexist oeuvre. Inundated with multi-platinum misogynist hip hop and rap, these girls have grown up with the pervasive message that violence against black women and girls is normal, natural, and justifiable. Coming full circle, the “Straight Outta Compton” narrative sacrifices their bodies on the altar of black masculine triumph and American dream-style redemption, signifying that the only occupying violence black America should really be concerned about is that perpetrated by the police.

7 Comments