“Race and gender are not the same!” is not a Good Response to the “Transracial” / Transgender Question OR We Can and Must Do Better

I remember Justine Black from elementary school. She was smart. She was brown, but not brown like me. I was black like most of the other kids in our class. I remember Justine because she was a good friend of mine. I knew that she was from some other place outside of the U.S. and not Africa (in elementary school I didn’t know how vast the black diaspora was), but when she told me she was black I took her at her word.

I relished in the fact that black could exist, could be pronounced and claimed proudly by this person, who could, if she wanted, be some other thing, some other race. In our school, being black was a privilege; it gave you a certain kind of currency. I know because I remember what it felt like to be called “white” because I was just too something else…I remember that no matter what anyone told me, I knew I was indeed black. And blackness seemed to be more than a designation. I didn’t feel like I needed to fight for the obvious. But I remember Justine, and I remember if someone got mad at her, I knew the deepest cut would come when someone would say, “Your middle name is ain’t!” Then a chant would move from murmur to rumble, “JUSTINE AIN’T BLACK! JUSTINE AIN’T BLACK! JUSTINE AIN’T BLACK!”

Race, and more specifically, blackness, was policed socially and there were moments when some people were made more vulnerable to being ousted than others. I remember the moments when the same students who joined in the chant one day had a sudden change of heart the next. They would fight for and co-sign Justine’s claim on blackness. She could be one of us. And even within the “us” some of “us” could be kicked out and charged with the damned sentence of “white.” I write of this childhood moment because I think it does a great job at illustrating the complex nature of race, particularly blackness.

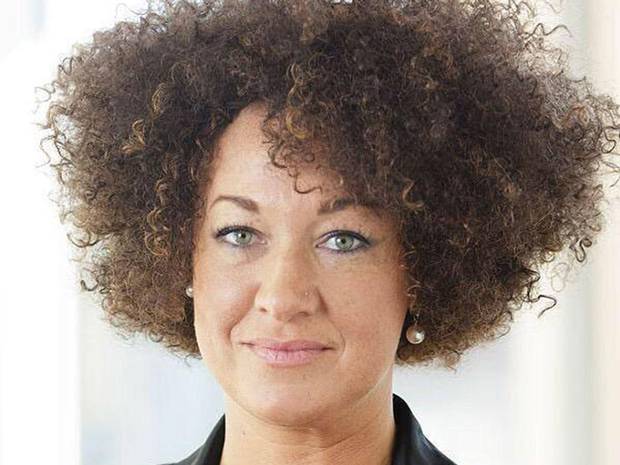

This past week I have been forced to reckon with the elasticity of the color line and its relationship to the gender line. Multiple memes, Facebook statuses, and tweets vilify Rachel Dolezal’s “becoming/being black” and the logic that has been used to damn her to “white” actually yields a transgender-antagonistic outcome.

The question many have asked: “If we accept Caitlyn Jenner as transgender, then must we also embrace Rachel Dolezal as “transracial”?[1] The response from many POC, Black, queer, transgender, organizers, scholars, theorists and artists has been to end the conversation with “Race and gender are separate.” To ask that question or put the two together in any way becomes transphobic. But the question itself isn’t transphobic. The answer that one arrives at, if you hold on to a historically situated notion of blackness and a presentist (gender is not only socially constructed, but historically naturalized) notion of gender, is transphobic.

In this moment we land in a messy and important intersection. The discourse surrounding the incident is both theoretically and materially destabilizing. Or perhaps this conjuncture once again reiterates the instability that is always already present when it comes to both the color line and the gender line. Race and gender are not the same, but they are both bio-social-historical categories that help to facilitate and enforce the unequal distribution of power and wealth under capitalism. It is important that in this moment we wrestle with these questions. We cannot just end the conversation because it makes us uncomfortable or angry. We must ask ourselves: What are the similarities between gender and race? What does this relationship reveal to us? How, why and when does it make us uneasy?

Many people in my circles (Black Radical, Queer, Trans, Feminist…) have decided that they no longer want to have this conversation regarding “transgender” and “transracial” because “they aren’t the same thing.” This is not a good answer and it is not a stupid question. It is a perplexing question; a hard one. The reason it is difficult is because it once again exposes us to what we already know — black is, and black ain’t. Many have responded to this conundrum of relation by stating that “I was born black and I don’t get to make a choice about that!” The truth is that many of us don’t get to make a choice. Our darker skin colors speak for us (and still it is not able to give the world the story of who we really are).

Rachel Dolezal made a choice; she decided to become black and whether or not you like it or agree with it is not the important question to me. A person can indeed become black because race is historically, biologically, and socially constructed! It is not just one of these things, it is all of these at work simultaneously. If you accept Caitlyn, then you have to accept Rachel. This incident pulls at the heartstrings of many people. Many black people who feel angry, harmed, and uncomfortable with the idea that someone who doesn’t posses the right historical and biological blood lineage is claiming blackness. But don’t we already know that the one-drop rule is a problematic one? And didn’t we all at some point originate biologically in Africa? How far back do we have to go to prove our racial allegiances?

Let us first discuss this term, Transgender. Transgender in this moment (this week) is represented or brought to us by Caitlyn Jenner. We have watched her transformation and we think that we somehow now know what transgender means, what it looks like, how to mark and name it. However, we take for granted the conjunctured nature of trans and gender. We say we know transgender, but I argue that we still really don’t know gender. Gender in the way that I understand it is also, like race, a bio-social-historical category that we all move through in different ways at different times.

- Gender is biological. I am not arguing that it is only biology, but we can agree that medical science assigns bodies at birth, via anatomic endowments a gender. We know that some people do not agree with that designation and decide to change it, perhaps to the opposite gender one was given at birth, perhaps to no assignment at all, or perhaps something for which we yet to have grasped within our grammar or politics of inclusion.

- Gender is socially constructed. Boys wear blue and play with trucks. Girls wear pink and play with dolls.

- Gender is also historically (re)produced. THIS IS a major point that must be reckoned with. For as my friend and colleague Michelle Wright noted in an email conversation, “…we understand race as historically produced and gender as ‘natural’ [but it is not].”[2] This is one of the most important places we need to go because this is the place where many are marking the distinction between race and gender, but it is an unproductive move. Gender like race has a history or multiple histories and it changes over time.

Now let us move on to race if we are to consider the new “transracial” to mean someone who changes their race, different from the one they were assigned at birth. Race, like gender is biologically determined, socially constructed, and historically (re)produced. There is a real logical connection between race and gender. The response for many has been: “This is my history that Dolezal is doing violence to!” It is about ownership over a past, one steeped in the colonial and white supremacist violence that traveled through the middle passage and continues to move (differently always) through present day white supremacist violence.

The black pasts and presents are not simply moments of struggle, loss, and pain. These are also moments of pleasure, joy, desire, and resiliency under horrific conditions. These are race- making moments—moments when the shape of blackness comes into view as it is defined as the deviant counter to whiteness’ tyranny. These histories and their contingent narratives are often carried in the flesh meaning that some people’s flesh sparks in others a memory of racialized terror. These folk look black like me, but there are other black people who don’t look black like me, some who look white like some other (dare I say) ancestor, but they too are black.

Race has boundaries. We police those boundaries, though we are not the only ones who do that policing. It is clear that Rachel Dolezal’s appearance has troubled the race police. I have heard arguments that she is purporting to take “our oppression” or she is pretending to be a black woman and her actions are disrespectful to real black people. These ARE the same arguments that people make regarding transgender bodies: “These men want to be women;” “They want to be oppressed and in so doing they distract from the real oppression real women face.”

When it comes to Dolezal the question is much more discomforting. She was born white. She decided to become black and live her life as a black woman. Geography matters: she made the choice to be black in Spokane—not, for example, Chicago or Atlanta. We are all responding to the question: Is she black or nah? We have too easily answered this question with a resounding NAH! But I think that’s the wrong question. The question we should be asking is when was/is she black?

Transgender visibility has appeared recently in a way that it has not before, mostly because before Caitlyn Jenner, the faces of this transgender moment/movement were transgender women of color like Laverne Cox and Janet Mock, but also organizers and activists like CeCe McDonald. What all of these women have in common is not simply their blackness and their transgender identity, but a radical black queer feminist politic. That is why I am so here for these women, because their embodiment of transgender is not the only way to embody transgender and they aren’t afraid to name that. Janet Mock calls out her own privilege, understanding that there are many stories that become further pushed into the shadows of now (and back then as in history) if we take her narrative as THE transgender narrative. There are many routes and many pathways to becoming. We need to pay attention to the multiplicity that is being named here and understand that there are many transgender bodies that don’t fit the scripts that are being most presented to us in popular media. I’m not arguing for more inclusion, I’m asking you to understand and be aware that there is always more there there.

Now that Caitlyn Jenner has made her debut as herself and many have applauded and affirmed her right to be and exist as she desires, we leave it at that. But Caitlyn Jenner is no CeCe McDonald. Caitlyn Jenner’s politics are not in line with mine. While I can support and affirm Jenner’s gender self determining processes that does not help to dismantle and create a new system whereby white supremacy and patriarchy are not the dominating structural formation that some of us seek to destroy.

Rachel Dolezal was outed by her biological parents as white. She has been lying to people and pretending to be something she is not, a black woman. People have said she’s been doing blackface. I disagree. I am not offended by Rachel Dolezal. I ask her the same question I ask Jenner: What do your politics look like? And what kind of work do you do?

It seems as though people have forgotten what we already know, which is that black has always been a porous entity. Some people do have a privileged relationship to blackness.[3] Not all black people relate to the category or are marked by the category in the same way. Your blackness might not be legible in certain places perhaps because of your complexion, or language, or accent, or hair texture. Dolezal reinforces and reiterates that black is a category that we all have the ability to move in and out of to a certain extent — my dark skin automatically situates me squarely as a physical manifestation of blackness, but there are people who are continuously questioned because their skin is of a lighter hue. We know this already. We also already know that racial passing has been going on since race was constructed, and no it wasn’t only black people passing for or becoming white. It was white people passing for or becoming a whole host of things (which included white too). When does passing stop being passing and become being?

I caution us to be very careful in this moment, as transgender can become a category that we take for granted. It is a category many think we know because we have seen it. It represents a move from one gender to another. But it is more than that. The gender binary is troubled and it is challenged. It is not only or always transgender people that we recognize as simply (or not so simply) moving from one place on the gender binary to another that do the troubling. There are many people for which transition isn’t just a moment and time to be completed. Some people live and reside outside or fluctuate between genders—this critique is one that collapses binaries.

The best response I heard in response to this whole matter came from writer Adrienne Maree Brown, co-editor of the new science fiction collection, Ocatvia’s Brood: Science Fiction Stories from Social Justice Movements. She posed the question “Any good sci-fi explanations or transformative justice responses for #RachelDolezal?” I seek answers to this question as a black transgender man, who is unapologetically black and unapologetically transgender. I cannot think gender and race separately. I have some agency in identifying with these two identity categories. I am black yes, but I choose to be unapologetically black and that is political choice. That decision is how I make my blackness mean or matter.

But blackness in itself is not a self-fulfilling prophecy (not everyone is unapologetic about it). The fact of blackness exceeds the category black. This doesn’t mean that black doesn’t exist, that some people don’t embody it. It does not mean that some of us have no choice in the matter of how we carry certain histories in the flesh. But we do not all carry our history in the flesh. Some of us carry it in our language, some of us carry it in our sway, some of us carry it by proclaiming it. I am unapologetically black. The unapologetic nature of my blackness compels fugitivity. I think we are supposed to accept blackness as a thing that has only been done to us. I think of people who ask, “who would choose to be this oppressed? This black? This queer?” I would and I do choose to be black as long as black holds this possibility of fugitivity and the desire to escape hegemonic control and order.

So what does transformative justice look like in this situation? I’m not sure that I have a real answer here, but I can’t respond by refusing to have the conversation. As I wrote on Facebook: “No, it’s not the same. But, yes there is some overlap and the discussion needs to be had. We need to put on our thinking caps (critical analysis) first. It’s not as simple as #rachelDolezal gives us Trans–racial and #caitlynjenner gives us Trans–gender. The latter we are to applaud and commend while the former we are to condemn to ‘mental illness’ and ‘inauthenticity.’ Something isn’t right here which is why I’m putting my thinking cap on.”

While I continue to put this thinking cap to work, I know for sure that I will not be joining the chanting chorus line of, Rachel Dolezal AIN’T black (no more). I am more concerned with whose blood is spilling on the sidewalk than whose blood is running through Dolezal’s veins.

[1] Transracial is a thing, a word that has significance prior to this moment. I think Lisa Marie Rollins does a great job of clarifying that here: http://www.thelostdaughters.com/2015/06/transracial-lives-matter-rachel-dolezal.html. I don’t think that forecloses the need to talk about the possibility of “transracial” in the Dolezal sense.

[2] I encourage everyone to read Michelle Wright’s new book, The Physics Of Blackness: Beyond the Middle Passage Epistemology

[3] Thank you Fred Moten for stating this so plainly.

Kai M. Green is a writer, scholar, poet, filmmaker, abolitionist, feminist and whatever else it takes to make a new and more just world. Kai is invested in developing models of healthy and loving Black masculinities. As a leader, teacher, and brother he is committed to raising consciousness around self-care, self-love, sexual health, emotional health, sexual and state violence, healthy masculinities, and Black feminism. He believes that writing and story telling are revolutionary acts, especially for those who are often erased by heteronormative and Eurocentric histories. He is currently a professor and Postdoctoral Fellow in Sexuality Studies and African American Studies at Northwestern University. Twitter: @Kai_MG

Pingback: The Blackface politics of Rachel Dolezal - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire

Pingback: On Rachel Dolezal, White Privilege, and White Shame |

Pingback: Die Geschlechterdifferenz gibt es, eine „Rassendifferenz“ gibt es nicht | Aus Liebe zur Freiheit

Pingback: ON TOPIC: WHAT WE'VE BEEN READING LATELY, PART II | Zubaan