The Authenticating Audience

By Guest Contributor on November 18, 2014By Louis Massiah

The experience of working with Toni Cade Bambara for close to ten years was an opportunity to collaborate with an ingenious and meticulous artist who was supremely conscious of the political power of culture. Her creative genius was applied in service to what she called “the community that names us.” The methodologies and creative concepts she developed in her art practice helped reinforce the responsibility of the artist to community. A central concept in Bambara’s work as a writer, filmmaker and teacher was that of the Authenticating Audience.

The notion of the Authenticating Audience is closely tied to the social-political enterprise of Cultural Work. Bambara’s self-definition as a cultural worker designated a practice of using art as a way to liberate, empower, and invigorate communities that have been historically oppressed and disenfranchised. In a 1984 video interview by June Givanni at the First International Feminist Book Fair in London, Bambara stated that her primary role as a cultural worker was to serve the needs of those real communities of people, who share common histories, class positions, raise families together, protect each other, name each other, and also share a common destiny. It is from this community that we locate the Authenticating Audience – a term that describes the dynamic connection between artists, art work and audience.

Bambara uses the term not as a sociological term or as a passive descriptor in a cultural studies sense, but as a foundational component of the creative process. Identifying this audience allows the cultural worker to evaluate the success or failure of the artistic practice. In Bambara’s documentary planning and scriptwriting workshops at Scribe Video Center in Philadelphia where she taught from 1986 to 1995, Authenticating Audience was a concept that gave direction to emerging filmmakers as they planned and shaped their work. The Authenticating Audience is also an aspirational and motivational term, for if an artist can clearly identify to whom she is communicating she is further empowered to create the work.

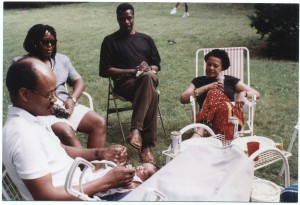

L-R Lamar Williams (with baby Ayodigi), June Givanni, Manthia Diawara, Toni Cade Bambara at the home of Frederica Massiah Jackson

photograph: © Louis Massiah, 1991

The need to identify an Authenticating Audience is also an acknowledgment of the boundless possibilities for a mass audience that arises in what Walter Benjamin described as “art in the age of mechanical reproduction.” When art is not only reproduced mechanically, but cloned digitally and distributed on the World Wide Web, there is the potential for an exponential increase in the scale of an audience. If an economic system privileges art works that can be commodified, increasing the audience size becomes a determinant for the “success” of the art work. Film work that does not aspire to a mass audience nor to being a commodity has little value in the market. On the contrary, when art is understood as a mode of political work, with the explicit goal of communicating a needed counter-narrative or analysis to a disempowered people, the success of an art work is more appropriately determined by how the community of focus is affected by the message. If the work succeeds in positively affecting this audience, then it succeeds and is authenticated.

Community media producers and independent artists that create work as an opening volley in a conversation with viewers can be more intentional if they have a clear vision of the audience. Certainly the community media projects that developed at Scribe, as well as the works by individual artists that emerged from Bambara’s workshops, were very much guided and empowered by this Authenticating Audience idea. This includes the Community Visions workshops at Scribe, which trained members of social service and activist community groups how to use video as a creative tool to reach their constituencies. Rather than seeing the finished edited work as a commodity, these art works aspired to be an articulate statement or thesis, which when shared with the constituent community could spark dialogue and action.

By redefining filmmaking as cultural work, Bambara’s workshops at Scribe helped participants re-contextualize the work of filmmaking. It led emerging filmmakers to consider the nature and definition of art, its role and utility. The work produced, the movie, is a medium and not an end in itself. The filmmaker/cultural worker is trying to affect a change in consciousness in the audience, provoke a response. This response could be as subtle as a change in perception, or it could be the catalyst to a dialogue between community members, between filmmaker and community, or perhaps a dialogue between those inside and outside the Authenticating Audience. But the goal, if the work is moral, is ultimately empowering the Authenticating Audience.

The idea of the Authenticating Audience is not a rationale to create artwork that is inaccessible to those outside the community of responsibility; rather it is a call for a cognizance and prioritization of a directed community. The opportunity to form allies and coalition outside the known community is desirable and welcome. Works of art that may have been initially produced for a specific audience may later have much wider distribution. And in that wider distribution the cultural worker has the opportunity to build movement and catalyze change.

The Authenticating Audience can change over time, which may demand changes in the artwork. As an example, in 1986, Toni Cade Bambara and I made The Burning of Osage, a documentary that attempted to place the 1985 Philadelphia police bombing of the MOVE organization into a broader context of state violence against African-Americans in Philadelphia and in the US more broadly. The documentary was produced for local public television broadcast in Philadelphia, a city trying to make sense of a tragedy that had been presented in mass media as an aberrational news event. Our first Authenticating Audience for Burning of Osage was certainly our neighbors in West Philadelphia, mainly African-American, who although familiar with the news event were still very undecided on the analysis and context of what had occurred.

When the documentary was selected for broadcast nationally on public television, we changed the title from The Burning of Osage to The Bombing of Osage Avenue, a less lyrical and more informational title, and provided further context, aware that this expanded broadcast was allowing us to communicate with new viewers who might not know some of particulars of the event. This expanded broadcast gave us the opportunity of communicating with a slightly different Authenticating Audience of poor people and people of color nationally, struggling for community control and against broader state violence.

The Authenticating Audience helps determines the voice of the art work, for when the cultural worker is clear to whom she is communicating, it is easier to determine the style and form of the communication and thus increases the chances for successful communication. In providing us with the concept of the Authenticating Audience, Toni Cade Bambara has provided a cadre of artists who have emerged from her workshops and lectures with an important tool. The concept and legacy that she has left for artists continues to empower.

Louis Massiah is an award-winning documentary filmmaker and the founder of the Scribe Video Center in Philadelphia, a media arts center that provides educational workshops and equipment access to community groups and emerging independent media makers. Massiah has developed community media production methodologies that assists first time makers use time-based visual media as a creative tool for authoring their own history. Currently, he is leading the Precious Places Community History project, a documentary video project composed of over 70 short documentaries produced collaboratively with neighborhood organizations in Philadelphia, Chester, PA, and Camden, NJ. He also is project director of the Muslim Voices of Philadelphia community history project. In late 2014, he will launch the Great Migration Project, a new collaborative community media project to celebrate the centenary of the beginning of the movement of African-Americans from the southern states to the industrial north.

Massiah’s award-winning documentaries, which include The Bombing of Osage Avenue, W.E.B. Du Bois – A Biography in in Four Voices, both written by Toni Cade Bambara; films for the Eyes on the Prize II series, and A is for Anarchist, B is for Brown, have been broadcast on PBS and screened at festivals and museums throughout the US, Europe and Africa. In 2011, he was commissioned to create a five channel permanent video installation for the National Park Service’s President’s House historic site. A graduate of Cornell University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Massiah has been a guest artist at Swarthmore College, Temple University, Princeton University, Haverford College, New York University and the University of Pennsylvania.

You may also like...

7 Comments

All Content ©2016 The Feminist Wire All Rights Reserved

Pingback: Rage and Meditation: Celebrating Toni Cade Bambara's 75th Birthday - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire

Pingback: Listen You Can Hear the Mothers Crying in the Universe: A Black Feminist Poet’s Requiem for Our Black Warrior Toni - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire

Pingback: My TCB Experience 1991-1995 - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire

Pingback: Toni Cade Bambara: A Woman of and for the People - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire

Pingback: Feminists We Love: Linda Janet Holmes [VIDEO] - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire

Pingback: Afterword: Toni Cade Bambara's Living Legacy - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire

Pingback: Toni Cade Bambara: '...an uptown Griot' - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire