Personal is Political: The Art of Getting to the Point

By Guest Contributor on November 25, 2014By Wesley Brown

Editors’ Note: This previously unpublished essay was originally written in 2002.

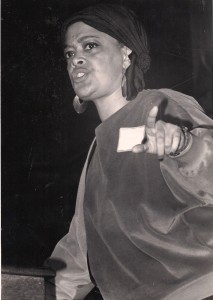

Toni Cade Bambara

Southern Rural Woman’s Network Conference, 1982

Photograph/Copyright: Monica F. Walker

In 1982, Toni Cade Bambara received (along with Paule Marshall and Toni Morrison) The City College Langston Hughes Award for Lifetime Contributions to African American Arts & Letters. At some point in the program, questions were taken from the audience. A woman asked the honorees why black writers weren’t giving their readers more positive stories about black life. Toni responded immediately, saying,

I’ve seen you before at literary events, like this one. And you always ask the same question. If there are stories that you want to see written, maybe that’s your assignment: to write them.

This was vintage Bambara, expressing the ethos behind everything she wrote: an unfailing directness which implicated the reader in the power of language and the responsibilities and consequences that come with using it.

In addition to Bambara’s confrontational relationships to language, she possessed the gifts for moving quickly to the vital center of a character or dramatic situation. This is quite apparent when reading the first lines of any of her short stories. For example, “Medley” opens with Sweet Pea who gets in our face very early in the sentence:

I could tell the minute I got in the door and dropped my bag, I wasn’t staying.

Sweet Pea has opened a door and witnessed something before the reader arrives on the scene. We don’t know what she sees; but whatever it is, her reaction tells us it’s not kosher. So we’re drawn to Sweet Pea’s displeasure, not because of any gory details, but because she has attitude to burn. You would never want to get in her way, but you’d follow her anywhere!

“Playin with Punjab,” like “Medley” cuts to the 411 on the person we’re about to meet: “First of all, you don’t play with Punjab.” I’m persuaded on the basis of the name alone. It’s not the same as “Kevin” or some other moniker unlikely to raise the fear level in the sweat glands. Just the sound: “PUNJAB.” It makes you wince, bracing yourself before receiving a blow. Another jarring sensation is delivered in the first line of Bambara’s “The Hammer Man”: “I was glad to hear that Manny had fallen off the roof.” Again, we’re not privy to the atrocity that must have been visited upon the narrator that would account for her casual reaction to the calamity suffered by Manny.

“Playin with Punjab,” like “Medley” cuts to the 411 on the person we’re about to meet: “First of all, you don’t play with Punjab.” I’m persuaded on the basis of the name alone. It’s not the same as “Kevin” or some other moniker unlikely to raise the fear level in the sweat glands. Just the sound: “PUNJAB.” It makes you wince, bracing yourself before receiving a blow. Another jarring sensation is delivered in the first line of Bambara’s “The Hammer Man”: “I was glad to hear that Manny had fallen off the roof.” Again, we’re not privy to the atrocity that must have been visited upon the narrator that would account for her casual reaction to the calamity suffered by Manny.

Here are more of Bambara’s teaser-driven sentences that create expectations, which are almost always fulfilled in her precise and attention grabbing prose:

“Blind people got a hummin jones if you notice.”

“That was the year Hunca Bubba changed his name.”

“The puddle had frozen over and me and Cathy went stompin in it.”

In each sentence, the conventional narrative floor, guiding us into the story, drops away, and we are sent into a riotous flight of language and storytelling.

My favorite Bambara opening line is from “The Lesson”:

Back in the days when everyone was old and stupid or young and foolish and me and Sugar were the only ones just right, this lady moved on our block with nappy hair and proper speech and no make-up.

That’s quite a load to unpack from the mouth of a sassy, adolescent named Sylvia who narrates the story. From the get go, Sylvia puts the world on notice that she’s peeped its pedigree and is not impressed. The reader need go no further to know that her every word and gesture says: NO TRESPASSING.

That’s quite a load to unpack from the mouth of a sassy, adolescent named Sylvia who narrates the story. From the get go, Sylvia puts the world on notice that she’s peeped its pedigree and is not impressed. The reader need go no further to know that her every word and gesture says: NO TRESPASSING.

But despite Sylvia’s warning, the world shows itself to be brain dead as well as pitiful, when an emissary named, Miss Moore shows up. For Sylvia, whatever mission brought Miss Moore to the neighborhood will come to nothing because she represents that category of being known as an adult. All this and more can legitimately be read into Bambara’s masterful first sentence, which satisfies Edgar Allan Poe’s requirement for any story to succeed artistically: to use only those words that are necessary to achieve the intended effect.

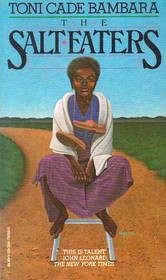

So where does Bambara’s skill for getting to the point early and often leave us? Do we come away merely dazzled by her virtuosity? These questions are, of course, more than adequately answered by reading the stories that unfold out of the first lines I’ve cited earlier. But perhaps the most telling example of Bambara’s vision as a writer comes, characteristically enough, from the first line of her novel, The Salt Eaters, where Minnie Ransom, a legendary spiritual healer asks Velma Henry:

So where does Bambara’s skill for getting to the point early and often leave us? Do we come away merely dazzled by her virtuosity? These questions are, of course, more than adequately answered by reading the stories that unfold out of the first lines I’ve cited earlier. But perhaps the most telling example of Bambara’s vision as a writer comes, characteristically enough, from the first line of her novel, The Salt Eaters, where Minnie Ransom, a legendary spiritual healer asks Velma Henry:

Are you sure, sweetheart, that you want to be well?

Here, Velma Henry is confronted by language that asks her to think about getting well, not as an intervention outside herself, but as an experience in which she is invested with the power to foster and undermine her capacity to heal. Once again, Toni Cade Bambara cuts to the chase and makes the case all in one motion. And that’s—point, game, and match.

Wesley Brown

June 7, 2002

Wesley Brown is the author of three published novels, Tragic Magic, Darktown Strutters, Push Comes to Shove, three produced plays, Boogie Woogie and Booker T, Life during Wartime, A Prophet among Them, co-editor of the multicultural anthologies, Imagining America (fiction), Visions of America (non-fiction), editor of the Teachers & Writers Guide to Frederick Douglass, and wrote the narration for a segment of the PBS documentary W. E. B. Du Bois: A Biography in Four Voices. He is Professor Emeritus at Rutgers University, currently teaches literature at Bard College at Simon’s Rock, and lives in Spencertown, New York.

Wesley Brown is the author of three published novels, Tragic Magic, Darktown Strutters, Push Comes to Shove, three produced plays, Boogie Woogie and Booker T, Life during Wartime, A Prophet among Them, co-editor of the multicultural anthologies, Imagining America (fiction), Visions of America (non-fiction), editor of the Teachers & Writers Guide to Frederick Douglass, and wrote the narration for a segment of the PBS documentary W. E. B. Du Bois: A Biography in Four Voices. He is Professor Emeritus at Rutgers University, currently teaches literature at Bard College at Simon’s Rock, and lives in Spencertown, New York.

You may also like...

1 Comment

All Content ©2016 The Feminist Wire All Rights Reserved

Pingback: Feminists We Love: Linda Janet Holmes [VIDEO] - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire