Black Blessings: Toni Cade Bambara and Octavia E. Butler

By Guest Contributor on November 23, 2014By Ayana A. H. Jamieson

The Octavia E. Butler Collection contains thousands of items from Butler’s life and career housed at the Huntington Library in San Marino, California, including some letters written between Toni Cade Bambara and Octavia E. Butler in the 1980s. The letters are at once private correspondence between trusted friends and womanist praxis. Reading their words transports me back to many occasions for bearing witness to grown folks conversation. At any moment, I expect Miz Toni or Mama Octavia to turn in my direction with that particular look in their eyes to let me know that if I listen quietly (pretending to mind my business) that I might learn something about how grown women communicate. I never had a chance to meet these two women in person, but they exist in the imaginal spaces created by their words. I read their letters as long distance conversations simultaneously situated within and transcending both time and place. Like the grandmothers, mothers, aunties, and other-mothers in our individual lives, Miz Toni and Mama Octavia exchange more than words and ideas.

As I write this contribution to the Toni Cade Bambara Forum, I realize that I am grown and I can time travel back to the 1980s as my grown self to read these letters and then return to the present to write this account. There are five letters in the archive Butler and Bambara wrote each other between May 24, 1980 and January 6, 1987. A portion of a March 31, 1984 letter from Butler to her fellow Clarion Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers’ Workshop (1970) comrade Marjorie “Maggie” Rae Nadler contains Butler’s description of her friendship with Toni Cade Bambara despite their contrasting personality traits. We have Butler’s letters to Nadler and Bambara, because she kept drafts of many of her letters as carbon copies, liked to type on erasable bond paper, and then Xerox them before mailing off the final copies. There are more letters from Butler to Bambara that I have not read in the Toni Cade Bambara Papers at Spelman College. Alexis Pauline Gumbs and others have has written about letters from Octavia to Toni in the past.

Butler’s Wild Seed and Bambara’s The Salt Eaters novels would both be published in 1980. Octavia is just shy of her 33rd birthday and Toni is 41 years old. Octavia had already sent Toni a galley copy of Wild Seed for her feedback on the manuscript prior to final publication. The first typewritten letter from Bambara is dated May 24, 1980. She has just returned from Mississippi, but sat right down to read Wild Seed straight through from start to finish and says it is “perfect, perfect.” She spends most of the letter praising the text overall, especially the ending:

Butler’s Wild Seed and Bambara’s The Salt Eaters novels would both be published in 1980. Octavia is just shy of her 33rd birthday and Toni is 41 years old. Octavia had already sent Toni a galley copy of Wild Seed for her feedback on the manuscript prior to final publication. The first typewritten letter from Bambara is dated May 24, 1980. She has just returned from Mississippi, but sat right down to read Wild Seed straight through from start to finish and says it is “perfect, perfect.” She spends most of the letter praising the text overall, especially the ending:

“Sun Woman, please don’t leave me.” His voice caught and broke. . . . He wept as though for all the past times when no tears would come, when there was no relief. He could not stop. . . He did not know the comfort of her arms, the comfort of her body next to him. He slept, finally, exhausted, his head on her breast, and at sunrise when he awoke, that breast was still warm, still rising and falling gently with her breathing.

—Octavia E. Butler’s Wild Seed (1980)

Bambara’s main criticism concerns the addition of an epilogue that follows the passage above. Bambara says the Epilogue shifts the tone too much, cheats readers, and begins with, “There had to be changes.” In fact, Bambara writes,

The Epilogue is TOTALLLLLLLLLLYYYYYYY unnecessary.

Even so, Bambara admits to loving all of Butler’s earlier books, except Kindred (1979), which she has not been able to bring herself to finish reading.[1] She says she can’t get past page 45 and then past page 82 of Kindred because she kept getting mad at what she thought was Butler’s move too far off her center and what “seemed to be a pro-racist sentiment and focus.” But she adds in parentheses that she will now go and read the whole thing non-stop. Later in the letter, she writes that Wild Seed will be the writing that goads her back to reading Kindred.

Even so, Bambara admits to loving all of Butler’s earlier books, except Kindred (1979), which she has not been able to bring herself to finish reading.[1] She says she can’t get past page 45 and then past page 82 of Kindred because she kept getting mad at what she thought was Butler’s move too far off her center and what “seemed to be a pro-racist sentiment and focus.” But she adds in parentheses that she will now go and read the whole thing non-stop. Later in the letter, she writes that Wild Seed will be the writing that goads her back to reading Kindred.

Finally, Bambara offers to do an in-depth retrospective review of Butler’s books, looking forward to another sequel and mentions the feedback she’s received on Salt Eaters. People keep telling her that she has broken new ground with her “phenomena/noumena ‘narrative’ ” or that she offers new writers a way to “ ‘meld the psychic-spiritual/realistic-usual.’ ” Bambara disagrees with them and points to writers like Butler, Ishmael Reed, Henry Dumas, and Charles Johnson.

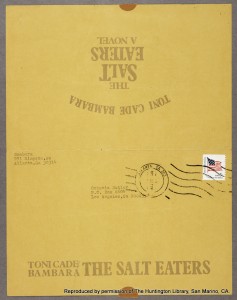

Promotional stationery for The Salt Eaters by Toni Cade Bambara postmarked May 24, 1980. A letter to Octavia Butler was typed on the reverse rise. This item is reproduced by permission of the Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

Even the ways their typewritten letters physically look seem to reflect their different personalities and preferences. Whereas Bambara’s first letter looks less than single-spaced, the characters all stacked on top of one another in one giant block paragraph with // marks to indicate breaks, Butler’s letter has a bit more breathing room. The ideas in Bambara’s letter seem to tumble over one another onto the page with her enthusiasm for Wild Seed, with all five paragraphs crammed onto the backside of one sheet. Bambara has used a promotional sheet for The Salt Eaters of goldenrod paper that is folded in half to form a postcard-sized mailer. Both of her 1980 letters were written on similar paper in a similar manner

Butler’s reply is dated October 9, 1980 and her tone seems warm but reserved. She begins by thanking Toni for all of the nice things she said about Wild Seed but disagrees with her about the epilogue. According to Butler, Anyanwu has to gain something more than just contrition from Doro. Ending the story with what Bambara had called a “perfect breathy ending” could have left the reader with the sense that Anyanwu was just giving in to Doro again, only this time through pleading and tears instead of threats. Including the Epilogue provides the evidence for Doro’s definite change, however small, which is a real victory. “I wanted to be clear that she’s won such a victory. What do you think of this? I do value your opinion,” Octavia writes.

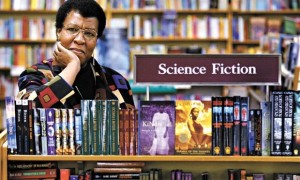

Next, Butler asks Bambara to contribute a piece for an anthology, Black Futures which she co-editing together with Martin Greenberg, an anthologist (who died in 2013) and Charles Waugh a knowledgeable science fiction author who digs up stories for reprinting. Black Futures is supposed to be a volume of science and speculative fiction in general by and/or about Black people. She says there is “a hell of a lot more ‘about’ that ‘by’” at that time because she is only one of three Black folks writing science fiction. Octavia’s comments about race and science fiction in 1980 are troubling, but the ways she identifies the various approaches to diversity in speculative fiction are still relevant today. She doesn’t want an entire volume on racism or the future of racism. She notes that “most white authors see racism in terms of clichés—big bellied Southern lawmen and people calling each other names.” Since characterization is a weak point of most science fiction writers, it is essential that there be works by Black people so they can characterize themselves. She wrote herself into the genre and she actively encouraged others to do the same throughout her lifetime. Asking Toni and other writers to contribute (with compensation and rights to their stories) is only one of the ways she tried to make this happen. She doesn’t want to have a book about what other people think of black people. Toni’s submission can be speculative or surreal, not just science fiction.

She closes her letter with a note telling Toni:

Hey, I’ll be looking forward to hearing from you. Don’t be like me. I know I take forever to answer letters, but even I’m mending my ways while we’re working on this anthology. Hope you’ll be in it.

She asks Toni for the review if she’s written it, includes an article she has written about race in science fiction, and adds a postscript with her phone number and the best time to call. Butler is still living in Pasadena, and Bambara is in Atlanta.

Butler gets her reply letter later the same month dated October 22, 1980. This time, Bambara has just returned from a trip to Brazil. Octavia’s letter is on top of the giant pile of unopened mail from her vacation. She is overwhelmed with needing to get things done but still has lingering memories from her time abroad. Getting back into the domestic responsibilities and refocusing her efforts will take some time. Bambara thinks that the anthology is a great idea and adds a parenthetical aside as a response to the article on race in science fiction: “Your article cracked me up you are soooo reasonable and logical and wry and serious and on target.” She does have something to contribute to the anthology from a collection of stories she’s been working on called The Last Quarter. It sounds like an eleventh hour near-apocalyptic theme where the protagonists must manifest various abilities or overcome certain challenges before it is too late. She then asks if Octavia has received her copy of The Salt Eaters yet so she can send her one if she hasn’t. Toni also concedes to Octavia’s choice for including the Epilogue to Wild Seed but notes:

Butler gets her reply letter later the same month dated October 22, 1980. This time, Bambara has just returned from a trip to Brazil. Octavia’s letter is on top of the giant pile of unopened mail from her vacation. She is overwhelmed with needing to get things done but still has lingering memories from her time abroad. Getting back into the domestic responsibilities and refocusing her efforts will take some time. Bambara thinks that the anthology is a great idea and adds a parenthetical aside as a response to the article on race in science fiction: “Your article cracked me up you are soooo reasonable and logical and wry and serious and on target.” She does have something to contribute to the anthology from a collection of stories she’s been working on called The Last Quarter. It sounds like an eleventh hour near-apocalyptic theme where the protagonists must manifest various abilities or overcome certain challenges before it is too late. She then asks if Octavia has received her copy of The Salt Eaters yet so she can send her one if she hasn’t. Toni also concedes to Octavia’s choice for including the Epilogue to Wild Seed but notes:

I think I see what you mean… except I think the reader, based on what you have TRAINED the reader thru the narrative process, understands the diff between the classic 5-minute aww baby, I’ll behave numbuh and the awesome powererfullness [sic] of sistuh and the transformation potential of Doro.

She hasn’t written the review yet, but still wants Butler’s agent to send her a packet of reviews for her books including new ones for Wild Seed. She says several times that the anthology is a good idea and gives OEB some leads and the promise of possible short story to contribute to the anthology.

I am struck by the way Toni Cade Bambara ended this particular letter telling Octavia Butler to take care of her energies and the closing words “Black Blessings,” which I borrowed for the title of this piece. This letter is on the back of another promotional sheet; it is also cramped and condensed with typewritten letters, but also overflowing with ideas, words, images, and names of people and places.

Over the next few years, there are no letters in the archives between Toni and Octavia, but they obviously saw each other and circulated in some of the same circles. In the March 31, 1984 letter to Maggie Nadler, Octavia writes that she is behind on all her correspondence. She has been working on Blindsight, an unpublished novel that she has been writing off and on since 1978. From the end of November of the previous year, when she returned from traveling several places, Butler had been working on yet another set of revisions. Catching up with Maggie is one of the first things she does once she sends off the draft. The way she describes Blindsight (formerly entitled The Dark), it sounds like a set of her own psychological complexes working themselves out through the writing. It isn’t done, it isn’t even monumental, according to Butler, but it is something that needs writing and rewriting like a compulsion. As the first title suggests, the subject matter is intense and dark. Through readings of the existing fragments of the unpublished novel, Moya Bailey and I recognize some of the same themes as some of Butler’s other published novels. In 1984, Clay’s Ark (another text I find intense and dark) has just come out and is in its second printing despite her publisher’s refusal to put out any ads for it.

Over the next few years, there are no letters in the archives between Toni and Octavia, but they obviously saw each other and circulated in some of the same circles. In the March 31, 1984 letter to Maggie Nadler, Octavia writes that she is behind on all her correspondence. She has been working on Blindsight, an unpublished novel that she has been writing off and on since 1978. From the end of November of the previous year, when she returned from traveling several places, Butler had been working on yet another set of revisions. Catching up with Maggie is one of the first things she does once she sends off the draft. The way she describes Blindsight (formerly entitled The Dark), it sounds like a set of her own psychological complexes working themselves out through the writing. It isn’t done, it isn’t even monumental, according to Butler, but it is something that needs writing and rewriting like a compulsion. As the first title suggests, the subject matter is intense and dark. Through readings of the existing fragments of the unpublished novel, Moya Bailey and I recognize some of the same themes as some of Butler’s other published novels. In 1984, Clay’s Ark (another text I find intense and dark) has just come out and is in its second printing despite her publisher’s refusal to put out any ads for it.

Octavia describes Toni Cade Bambara to Maggie Nadler as she recounts her travels of the past year when she stayed overnight with Bambara in Atlanta. In her self-deprecating way, Butler says that she got “dumped on Toni” when someone went off with the university guesthouse keys where she was supposed to have stayed. Since they’d exchanged letters, they weren’t total strangers.

She’s this energetic eager activist who is probably incapable of sitting back and saying, “Someone ought to do something about that!” whatever “that” might be. She just goes out and does it. Of course sometimes she fails or makes an absolute fool of herself, but it never seems to occureto [sic] her that this might be the reason to lie low next time. She just dives in. I tend to go away. Either I can do something about thesituation [sic] or I can’t or I can; but it’s not worth it. I remember saying to her, “I’m not only a hermit, I’m really a low-energy person. I use what energy I can stir up on my work.” She said that was a California attitude. Imagine. My whole state stuck with my personal deficiencies. I don’t think most of the other people here would care much for that.

Regardless of the difference in energy levels, Octavia says that she found herself liking Toni the same way she liked one of their Clarion writing teachers, though Toni and the teacher would probably be enemies in a half an hour because the two were too much alike. They were “high-energy people running around getting everything done—or at least getting themselves involved in everything.”

There are two more letters in the archive both written from Toni Cade Bambara to Octavia Butler. The first one dated December 14, 1985. This letter is harder to read because it is handwritten. She says she understands what Octavia means about “riffing off the energy” of other writers and she’s thinking of starting up a writers workshop there in Philadelphia where she has just moved from Atlanta. Bambara writes,

I miss the mutual generation of writer-intensive focusing.

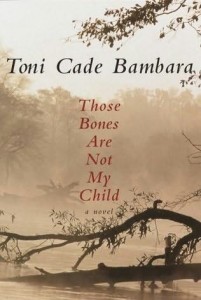

Bambara is editing and fine-tuning If Blessings Come, “the Atlanta missing and murdered children’s novel” that would become the posthumously published Those Bones Are Not My Child and outlining another text about a Black vaudeville group from New York that went to Europe in the 1930s and got caught up in the Nazi round up. Several Black folks ended up in camps with the Senegalese and others of African descent from other colonized places or were previously living in Germany. Many of them lost their lives in the death camps, fought for the Resistance, and so on. She “cannot STAND” the silence on this particular erased history, and she can’t wait to get back to work on it.

Bambara is editing and fine-tuning If Blessings Come, “the Atlanta missing and murdered children’s novel” that would become the posthumously published Those Bones Are Not My Child and outlining another text about a Black vaudeville group from New York that went to Europe in the 1930s and got caught up in the Nazi round up. Several Black folks ended up in camps with the Senegalese and others of African descent from other colonized places or were previously living in Germany. Many of them lost their lives in the death camps, fought for the Resistance, and so on. She “cannot STAND” the silence on this particular erased history, and she can’t wait to get back to work on it.

Bambara writes, “I’m so pleased to be coming into my stride at this moment in our history.” Butler is in the middle of writing the Lilith’s Brood trilogy, and Bambara tells her that it must be good to be feeling to have just sent off the second book in the trilogy.

The final letter dated January 6, 1987 from Philadelphia begins,

Ahhh, my sister, what incredible timing. Your name’s been in my mouth all week.

Bambara has been making arrangements for Butler to visit the museum for a writer’s series, and the museum has not been very good at getting the word out. She says she is looking forward to seeing her and knows what Butler means about the “absence of friend-readers.” She says this is the first time she’s gone so long without pulling together a workshop, collective, or group of some kind “to make this whole business less soul-weary lonely.” By this time, Octavia is 40 years old and Toni is 47. Toni Cade Bambara’s award-winning documentary The Bombing of Osage Avenue [1] is about to be broadcast on PBS.

She gives Octavia the local Los Angeles date and time of the upcoming broadcast. She also talks about how her daughter “Miz Girl” is fine and getting ready to go up to Howard, menopause, her almost empty nest, children in general, aunties, and the other “non blood kin” who were “close all the same.” Toni has been one to notice grown folks, grown women who were essential to her growing up from childhood onward. She says she’ll be seeing Octavia in February.

The final letter in this set seems the most poetic, measured, and perhaps the most filled with memories, compassion, and some nostalgia. It is the only one of Bambara’s letters with handwritten corrections over a neatly typed, four-page, double-spaced document. It is still full of information, details, and projects that Toni is interested in, working on, reading about, but it is not hurried or hasty. I read it aloud and imagined it performed as part of a one-woman play like Letters from Zora: In Her Own Words that I saw in Butler’s native Pasadena, California. Their friendship seemed to have deepened over the years even though their respective energies were so different.

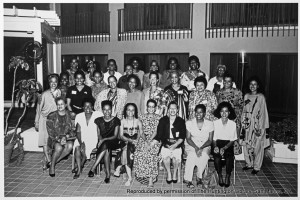

1988 Nassau Bahamas, Essence Writers’ Retreat. This item is reproduced by permission of the Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

Seated (from left) Dr. Julianne Malveaux, Betty Winston Baye, Stephanie Stokes Oliver, Sonia Sanchez, Thulani Davis, Ntozake Shange, Valerie Wilson Wesley, Bebe Moore Campbell.

Second row, from left Toni Cade Bambara, Elsie Washington, Barbara Smith, Marlene NorbeSe Philip, Bonnie Allen, Sherley Anne Williams, Cheryll Y. Greene, Ayesha Grice, Phyl Garland, Ivy Young, Elaine Brown.

Last Row, from left Susan L. Taylor, Lena G. Sherrod, Renita Weems, Jean Wiley, Audrey Edwards, Jill Nelson, Vertamae Grosvenor, Octavia Butler, & Lucille Clifton.

In November 1988, Essence Magazine had a writers’ retreat in Nassau, Bahamas. Toni Cade Bambara, Octavia Butler, and many other Black Women writers attended. It is one of the many times their paths crossed throughout the year. You can listen to and read Betty Baye’s 2007 NPR account of the 1988 retreat, “A Conference to Write Home About.”

Reading these letters for the Toni Cade Bambara Forum has Black Blessings on my mind. I wonder about how Toni and Octavia had much more in common than I have considered before through their individual ways “black” overlaps. More than just moving through the world with different kinds of personalities and energies, they each had the capacity for holding and processing archetypal darkness into art, documenting themselves, and the rest of us in ways that have yet to be explored. The mythical darkness is also generative. The shadows of death and decimation will not remain in the dark, and new generations of artists, activists, organizers, and writers will continue to need models for navigating darkness. Out of decay, soil, and rot, seeds grow into new organisms. At this present historical time, I wonder what each of these writers would have written or said or spoken about the higher visibility of shooting unarmed people, missing women, and other darknesses that surface daily. I have written elsewhere about multicultural mythologies and the orishas in Butler’s work, particularly Oya’s aspect as the one who dwells at the threshold of life and death. Oya is the entity who bestows the change of Black Blessings like the ones I read in these letters. It is with gratitude that I think about the legacies of Octavia Butler and Toni Cade Bambara in relationship and how we can be in relationship with one another.

[1] By this time Patternmaster (1976), Mind of My Mind (1977), Survivor (1978), Kindred (1979), Wild Seed (1980) have been published. The Patternist series would not be reordered as the Seed to Harvest compilation (which excludes Survivor) until 2007. While Kindred is a standalone novel and the internal chronology of the Patternist books does not match the order of publication. Wild Seed is the first book in the series, followed by Mind of My Mind, Clay’s Ark (1984), Survivor, and finally Patternmaster. Bambara either has read and forgotten Survivor or not read it at all because she asks Butler if there will be three books in the series, presumably in addition to Mind of my Mind and Patternmaster which she also mentions.

[2] The Bombing of Osage Avenue was written by Toni Cade Bambara and produced and directed by Louis Massiah

Ayana A. H. Jamieson, Ph.D., is the founder of Octavia E. Butler Legacy Network, and teaches for the Center for Distance Learning at State University New York, Empire State College. She teaches courses on speculative and science fiction, mythology and modern life, and race, class, and gender. She earned a doctorate in Depth Psychology at Pacifica Graduate Institute, where she also completed her master’s degree. She received her bachelor’s degree in theatre from California State University, Pomona. Ayana’s dissertation “‘Certainty of the Flesh’: A Biomythograchical Reading of Octavia E. Butler’s Fictions,” explores Butler’s biographical origins and the mythic aspects of her literary work. She is currently conducting research in Octavia Butler Archives for a book-length project, and organizing Octavia Butler events in collaboration with other members of OebLegacy in digital and physical spaces. Here you can find Ayana’s blog, the OebLegacy website, @OebLegacy on Twitter, Tumblr, and Facebook.

You may also like...

3 Comments

All Content ©2016 The Feminist Wire All Rights Reserved

Pingback: In the Media: 30th November 2014 | The Writes of Woman