Personal is Political: White Beauty: At Home and Abroad

By Amalia Clarice Mora

Throughout my life, I have overheard countless conversations, countless comments by white friends, acquaintances, strangers, or family members making pejorative remarks about the physical features of black, Hispanic, Asian, or Middle Eastern people. White male friends (ashamedly) admitting that though they aren’t physically attracted to black women, they have been turned on by them in porno videos. A white stranger discussing the repulsive, animal-like purple gums of an Indian-American woman he was on a blind date with. White female acquaintances grimacing at the thought of making out with an Asian guy. It has obviously bothered me that these white individuals’ notions of beauty have been shaped and are perpetuated by racism and a racist media. But what has disturbed me even more or, rather, what has really pained me, is the extent to which my friends of color, family members, and acquaintances have also internalized a white or “whitened” standard of beauty.

Throughout my life, I have overheard countless conversations, countless comments by white friends, acquaintances, strangers, or family members making pejorative remarks about the physical features of black, Hispanic, Asian, or Middle Eastern people. White male friends (ashamedly) admitting that though they aren’t physically attracted to black women, they have been turned on by them in porno videos. A white stranger discussing the repulsive, animal-like purple gums of an Indian-American woman he was on a blind date with. White female acquaintances grimacing at the thought of making out with an Asian guy. It has obviously bothered me that these white individuals’ notions of beauty have been shaped and are perpetuated by racism and a racist media. But what has disturbed me even more or, rather, what has really pained me, is the extent to which my friends of color, family members, and acquaintances have also internalized a white or “whitened” standard of beauty.

I went to a very rare kind of American private high school. It was an all-girls Catholic school in which Caucasians were a minority. The parents of the ethnic minorities at my school had pushed their children to work hard, assuring them that they could one day join the big leagues along with rich white kids. In fact, many of the students who struggled the most academically were white. However, in spite of our schools’ commitment to celebrating ethnic diversity, it still seemed as if everyone talked about and wore beauty as if it were something white. There were, for instance, the Korean-American girls with blonde-streaks in their hair, who flashed blue and green eye contacts. Their eyeliner was drawn on in such a way to make their eyes look wider, whiter. One day, a white student made her eyes squinty with her hands and mimicked a Korean accent as she said, “I smell like feeesh.” The Korean-American girls giggled with a kind of uncertain laughter. They didn’t like being made to feel ugly, but they seemed to like that Miss Pretty was laughing with and not at them.

In college, I became friends with a stunningly beautiful black girl. At one particular point in time, we found ourselves at parties frequented by white skater boys on the prowl for apple-pie-faced “all-American” girls. My friend was known as “the crazy black girl” at such events. She’d sing loudly off-key and paint her breasts with ketchup, anything to make herself feel that she was un-liked by the boys because she was crazy, not because she wasn’t white enough. This suited the white partygoers just fine, because as she enacted the blackness that they expected to see (the overly sexed, comic sidekick), they felt reassured of the access they had to normative attractiveness.

As a young adult, I worked as an usher at a local theater with mostly non-white co-workers. Sometimes my male co-workers would point out the women they thought were particularly attractive. Tellingly, the women of color they’d point out tended to be ethnic in the same way that Halle Berry, Jessica Alba, or Maggie Q are. In other words, these women tended to have thin noses, light(er) skin, and round eyes. For the most part, the women they found to be the most beautiful were judged as such by virtue of their whiteness or “close-to-whiteness.”

As a young adult, I worked as an usher at a local theater with mostly non-white co-workers. Sometimes my male co-workers would point out the women they thought were particularly attractive. Tellingly, the women of color they’d point out tended to be ethnic in the same way that Halle Berry, Jessica Alba, or Maggie Q are. In other words, these women tended to have thin noses, light(er) skin, and round eyes. For the most part, the women they found to be the most beautiful were judged as such by virtue of their whiteness or “close-to-whiteness.”

It’s not just whiteness, but lightness, that grants privilege. Though I have experienced racism and discrimination on many occasions, I have also benefitted from white/light privilege because of my ambiguous-looking ethnicity. My dad is Mexican-American of mostly Amerindian descent, and my mom is of European and partially Native American descent. But most Americans assume I am Arab or of some other kind of “brown-ish” ethnicity. “You don’t look too ethnic though,” an acquaintance once said to me. This, apparently, was a good thing. In fact, people I know of all racial and socioeconomic backgrounds have expressed this you don’t look too ethnic though and that is a good thing sentiment. The mixed people are so beautiful sentiment, which often really means white-ish looking people with an ethnic twist are so beautiful or ethnic people with white features are so beautiful.

After graduating from college, I went abroad, looking for a place that hadn’t been influenced by white standards of beauty. Unfortunately, I never found it.

While in Mexico and Central America, I noticed many romantic relationships between local men and white foreign women. Some of my male friends explained to me that white foreign women are considered desirable because they are perceived to be sexually loose and because they are considered “hot” by virtue of their whiteness and the social and economic status that whiteness represents.

I’ve encountered similar attitudes in India, where I’ve spent a considerable amount of time. Countless individuals, from a wealthy developer to a friend who works in a shoe-shop, have informed me, quite openly, that Indian men have a thing for “white-skinned” women. Throughout my various trips to India, acquaintances have warned me about getting any darker than I already am. Others have told me that I am beautiful because I look like a “Brahmin” girl, and when I’ve asked them to clarify what they mean, they’ve said that a Brahmin girl looks sort of European, sort of Indian, with light skin and dark hair. One friend matter-of-factly told me that white people just naturally have more beautiful features.

I’ve encountered similar attitudes in India, where I’ve spent a considerable amount of time. Countless individuals, from a wealthy developer to a friend who works in a shoe-shop, have informed me, quite openly, that Indian men have a thing for “white-skinned” women. Throughout my various trips to India, acquaintances have warned me about getting any darker than I already am. Others have told me that I am beautiful because I look like a “Brahmin” girl, and when I’ve asked them to clarify what they mean, they’ve said that a Brahmin girl looks sort of European, sort of Indian, with light skin and dark hair. One friend matter-of-factly told me that white people just naturally have more beautiful features.

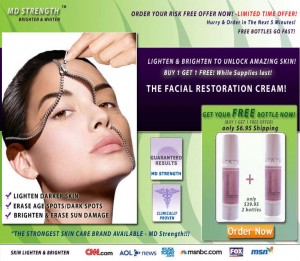

When I went to Thailand, the ubiquity of facial and body fairness creams in stores shocked me, as did the amount of advertising for non-surgical facial reconstruction to thin out the nose and widen the eyes. Many people of color outside of the U.S. reference the old adage “the grass is always greener” to explain why many people of color idealize light skin. I’m not so sure. White folks used to idealize sheet-white skin back when it symbolized wealth and status. Having pale skin was a way of flaunting the fact that they didn’t have to work laboriously in the sun. Today, it is tanned skin, not pale skin, that symbolizes beauty. Because who except well-to-do, leisured individuals have the time to lie in the sun for hours? Furthermore, there may be many, many white people who tan, but there aren’t too many on the hunt for plastic surgery to make themselves look black or indigenous. In other words, most white people who tan aren’t doing so in order to appear non-white.

Far from being a universal feeling, then, the “grass is always greener” seems to be a sentiment that people of color experience more than white folks do. A white family friend of mine from Northern Europe believes that human beings are attracted to the familiar. He has, on several occasions, told me that he finds “ethnic-looking” and “Spanish-looking” women unattractive because he grew up around Northern-European-looking blonde women. However, not every woman he grew up around was white or blonde. And what about people like me who grow up in multi-ethnic environments? Why do I know so many people who, in spite of their diverse surroundings, express a particular attraction to white or partially-white beauty?

In a way, my family friend was on to something. Even if people in Los Angeles and beyond have not grown up around white or mixed-race people, what they have grown up around is the ubiquitous image of white or light beauty on television, in films, on advertisements plastered to barber shop windows, on billboards, on products.

Who we express a particular attraction to depends largely on the kind of beauty revered in the sociocultural surroundings in which we grow up, and for everyone who has watched TV or seen advertisements, these sociocultural surroundings are racist. It’s tempting to let ourselves off the hook when it comes to aesthetic preference, to see attraction as something personal, not political. But attraction is very much political and rooted in the real, social world. We have to recognize that there is a reason why people with various features have been considered pretty or ugly at different moments throughout history. And if we fail to really acknowledge this by examining perceptions of attractiveness, we are failing to dig down deep to the dirtiest part of ourselves, the embarrassing part, the part we don’t want to think about. And we make ourselves complicit in something that seems innocent enough. If we fail to acknowledge this, we allow for a racist “system of feeling” to exist among us, cocooned, safe, secret. And this “system of feeling” ends up desensitizing us to other, much more dangerous kinds of discriminatory attitudes and practices.

Who we express a particular attraction to depends largely on the kind of beauty revered in the sociocultural surroundings in which we grow up, and for everyone who has watched TV or seen advertisements, these sociocultural surroundings are racist. It’s tempting to let ourselves off the hook when it comes to aesthetic preference, to see attraction as something personal, not political. But attraction is very much political and rooted in the real, social world. We have to recognize that there is a reason why people with various features have been considered pretty or ugly at different moments throughout history. And if we fail to really acknowledge this by examining perceptions of attractiveness, we are failing to dig down deep to the dirtiest part of ourselves, the embarrassing part, the part we don’t want to think about. And we make ourselves complicit in something that seems innocent enough. If we fail to acknowledge this, we allow for a racist “system of feeling” to exist among us, cocooned, safe, secret. And this “system of feeling” ends up desensitizing us to other, much more dangerous kinds of discriminatory attitudes and practices.

_________________________________________________________

Amalia Clarice Mora is a doctoral candidate in ethnomusicology at the University of California, Los Angeles. Her doctoral research examines how tensions related to class, caste, and gender are negotiated within the context of music tourism in Goa, India. Her other research interests include interracial attraction and mixed race experiences in the U.S., and how sociocultural anxieties related to both manifest themselves in unofficial discourse and texts, such as rumor and internet comment sections.

Amalia Clarice Mora is a doctoral candidate in ethnomusicology at the University of California, Los Angeles. Her doctoral research examines how tensions related to class, caste, and gender are negotiated within the context of music tourism in Goa, India. Her other research interests include interracial attraction and mixed race experiences in the U.S., and how sociocultural anxieties related to both manifest themselves in unofficial discourse and texts, such as rumor and internet comment sections.

3 Comments