Why Sikivu Hutchinson’s Latest Book Is Relevant To an Angry Romani Ex-Muslim

By Maryam Moosan-Clark

In Godless Americana: Race and Religious Rebels, Sikivu Hutchinson takes us on a roller coaster ride through the different, interacting forms of underprivilege that affect People of Color in the United States, past and present. Throughout much of the journey, despite giving numerous examples a minority person can relate to, she maintains a measure of intellectual distance necessary for proper analysis. This changes on the final pages, where she shares one historical and two personal experiences of loss (one still bearable for someone who is a parent, one not) which make everything discussed in the book suddenly and painfully concrete. Godless Americana is thoroughly researched and properly sourced, which is not a given for an activist book and should make the lives of racism denialists somewhat harder. Sikivu’s mastery of language, as she alternates between intellectual and activist, makes for a very captivating read, especially considering the sobering nature of the book’s content.

Many of the patterns discussed in Godless Americana can be transposed to the situation of islamized minority cultures, such as the Khorakhane Romani people, but also in part to Non-Arab, Islam-colonized nation states. To understand this, some context is required. As Hutchinson points out, many white non-believers renounce their former faiths on purely intellectual grounds. Often, the same insight in a minority person merely leads to closet Atheism where, for reasons of social acceptance, one remains a member of the dominant religion in name. An additional impetus is usually required for such a person to come out as an Atheist (capitalization intended). The most common are socialist political views, the causes of women, gender and sexual minorities, and anti-racists. For me, and interestingly also for the other Ex-Muslims in our immigrant freethought group, it was the latter.

At some point, I had to admit however reluctantly that the purportedly liberating, universalist, anti-racist religion I had been raised in was actually a racist, colonialist political ideology that promoted Arab supremacy and immunized itself against opposition by also being a religion. I realized that Turkish and to some degree Persian people had managed to bend the ideology to acquire a privileged position in the same way white Europeans have adapted Christianity to their needs. It was this racial hierarchy, which works to the detriment of my people, that ultimately convinced me of the necessity of Atheism. Godless Americana treats white supremacism and the Christian religion as separate but interconnected phenomena. Whereas in the Islamic world, Arab political and cultural imperialism are blended into one, the collection of causes and effects is ultimately the same. The most important commonalities are discussed below.

While this is not explicitly stated, Godless Americana shows how more than two centuries after slavery forced the transition from extended to nuclear families, African American culture has yet to recover from it, and this is one of the many factors that negatively affect the lives of women. Among the Romani people, this transition is in various stages, depending on whether it was or is driven by slavery, genocide, or migration. Most of the time, however, it happens as involuntarily as it did for African Americans. Unlike white people, for whom this was a gradual process over more than a century, our two peoples have had very little time to adjust. This disproportionally affects women, to whom the responsibility for family work traditionally falls, and it leaves broken homes and dysfunctional families in its wake.

Hutchinson repeatedly highlights the proprietary relationship between a white master and the body and produce of his other-race bondwoman as the archetypical form of racist-sexist exploitation. This too is a common theme for islamized ethnic minorities. There is the Romani sex slave from the Balkans, whose Arab- or Turkish-owned body is available for rent by White-European males. Unlike her indentured white counterpart, she cannot buy her freedom. Her children are to be removed by forced abortion. She is a piece of factory equipment with productivity metrics, a price tag, and no way out. There is the Asian or African maid in an Arabian peninsula household who, unlike her Arab counterpart, is not merely an underpaid worker who is free to leave any time. She can say the shahada all she wants, her race makes her less than a full Muslim, and consequently any protection from sexual exploitation by her master does not apply to her. Her children are sent to her native country at best, and offloaded via black market adoption (the proceeds of which the mother never sees) or “made to disappear” at worst. In my community work with Eritrean asylum seekers who escaped from Gulf countries in adventurous ways, sexual abuse has been a recurring theme. While at first glance this relationship appears to be discouraged by religion, it is facilitated by it in reality (even more overtly in Islam than in the Christian context Hutchinson describes).

Another central issue discussed in the book is the distinction between the purity of “master-race” women and the supposedly feral sex drive of “lower-race” females. This pattern repeats itself in the Islamic world, albeit literally veiled behind an additional layer of complexity. According to Islam, all female sexuality is impure temptation and must thus be hidden from the public eye. But while this concept is relatively strictly enforced in Arabia, the picture is very different in the Western proving grounds of Islamic power mongers. The purity of Arab women such as Ameera Al-Taweel is not compromised by their appearing at Clinton family fundraisers with flowing hair and high heels. Yet, Arab-funded campaigns seek to rigorously confine Muslim immigrant women of Pakistani, Indonesian, Albanian, African, or Khorakhane (Middle-Eastern Romani) descent behind veils, turn them into sexless beings, as their savage lower-race bodies lack the invisible hijab woven from the purity of an Arab princess. A long, figure-occluding skirt was a must for a high-school going Khorakhane Romani girl, as the Arab imam so wisely told her parents at the Mosque. The tight jeans of his teenage Arab parishioners who used to walk by his house every day never seemed to bother him. I could give several dozen variations of this account, as told to me by Non-Arab, Ex-Muslim women. It is also no coincidence that the greatest veil-related excesses are found in places such as Pakistan or Afghanistan.

Hutchinson further examines how religion forms the basis for feminist activism in African American and Latina paradigms. Especially relevant here is the transition from orthodox religion to more liberal spirituality. Faith itself is seen as a fixed element that cannot be abandoned, and significant amounts of energy are invested into salvaging it. This pattern is all too familiar among islamized cultures. From Irshad Manji to Malala Yousafzai, Non-Arab feminists in our world use the colonial ideology of Islam as a source of personhood and identity. Passages from the Qur’an and Hadith are taken out of context and reinterpreted with considerable creative license, elements which encourage, or appear to encourage, critical thought are cherry picked, while the bulk of oppressive content is ignored and explained away with intentionally vague and irrational language. This creates a heavily encumbered form of feminism whose liberating power is limited by the dead weight of its religious apologetics.

The book goes on to describe how women, who are given very little maneuvering space in the real world, seek agency in the virtual world of church rituals. This phenomenon was clearly visible in the predominantly African American mosque my family attended during our final year in the United States, among both black and Romani women. But was it really agency they sought? There isn’t much of that for female parishioners to find in a mosque. What I noticed was how tired these women were, no matter how ecstatically they prayed. It seemed to me they came mostly for a break, a pause in their daily routine of being the invisible engines of family life, which gave them an opportunity to just let go and be carried away by the ritual.

I had to smile when I read about fraud schemes being pitched at African American churches. Fundraisers for opaque, supposedly charitable organizations are such an integral part of mosque culture, it makes you weep. From savings plans for your hajj, to investments in Muslim immigrant businesses (guaranteed interest-free, of course), to donations for mosque construction in developing countries, you got the whole shebang. And they were always pitched to Non-Arabs with particular vigor, because we were gullible enough to be easy marks. The proceeds of such collections often ended up in someone’s private account or worse, in the hands of some islamist campaign, or even a violent group. My family, although struggling to make ends meet, was particularly receptive to such campaigns. After all, it was never wrong to please Allah. This demonstrates why the pervasiveness of religion in minority communities, despite its role in organizing and providing infrastructure, should not be taken lightly. Faith, and its associated thought patterns, sets the precedent which allows such schemes to work. Religious communities are fertile grounds for fraud, because religion is fraud.

An interesting aspect of African American Atheism that Hutchinson mentions is its strained relationship with white Atheism. This exists in even more extreme form within the Ex-Muslim paradigm, where we see outright perverse alliances between Ex-Muslims and the Christian Western Right, and conversely between the secular Western Left and Islam. Seeing Ayaan Hirsi Ali join a right-wing think tank, was as much an unpleasant surprise, as it is frustrating to see Western liberals form a protective circle around Islam to shield it from opposition. The white sense of entitlement includes the presumption that one is qualified to understand matters without ever educating oneself, and individuals who identify as skeptics, sadly, are not immune to this. The same mentality which inspires white Atheists to bring token African Americans to their conferences for PR purposes causes them to believe that, by defending Islam of all things, they can establish themselves as anti-racists.

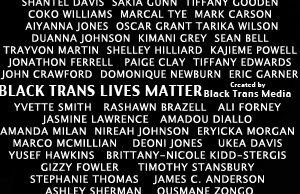

Vigilante justice and its application against African Americans, which forms part of the book’s historical overview, created a major deja vu effect for this reader. It is not just a common theme in the Islamic world, but actually mandated by the religion, and as usual with such things, it is disproportionally applied against minorities. Romani people in the Ottoman empire were frequent targets of barbaric punishment by mobs, such as stoning and the amputation of limbs. Lynch culture and its “civilized” successors, the assumption of guilt, the school-to-prison pipeline, ever-present suspicion, and the constant watching and waiting for one of us to take a wrong turn and thus confirm all master-race suspicions, are a hallmark trait of institutional racism. As a member of the ultimate “dark twin race” to the native, sedentary, rooted, steady, hard-working, uniformed, moral, dependable, honest, intelligent, social, attractive, white majority, this is the part of the book that resonated with me the most. It is also interesting to note in this context that the gradation of under-privilege between African Americans of darker and lighter skin exists among my people as well. Those of us who are sufficiently mixed with Europeans to “pass as white” are more likely to escape the modern incarnations of lynch culture (until people learn they are Romani) than those who – like my own family – never mixed and thus look distinctly brown.

Overall, Godless Americana provides a thoroughly researched analysis of the interaction between past and present, racist and sexist oppression, superstition, and opposition to those things, which holds up to very high standards. In plain words, it is one of the best books on intersectionality I have read. I should, however, mention that it is not without its problems and omissions (although far fewer than usual). While a full rebuttal on those points would exceed the scope of this review (and my spare time), I will sketch five of these issues in the following paragraphs:

One omission from the list of interacting privileges that I’d like to note, since the book concerns itself with youth, is ancestral privilege. While this may elicit amusement from some individuals, its effects are not restricted to seemingly funny, but still unnecessarily frustrating, lines such as “you can choose your clothes once you’re old enough to buy them” (gosh, how I hated that line). Among islamized cultures, but also in Christian circles, there is a strong, religion-mediated, proprietary relationship between parent and child. Rather than providing options and methods of discovery, parents assume the right to define the personality, thought, and behavioral patterns of their offspring far beyond ensuring social function – culminating in obscenities such as arranged marriages. The justification is usually “my parents did it too, and I lived” or “that’s how our culture works.” This is one of the primary mechanisms by which superstition, misogyny, various phobias, and violence are passed down from generation to generation.

Also, while the book speaks about the lack of real-world role models for our youth, it does not really explore the topic of fictional role models. There is a glaring lack of empowering children’s literature for girls of color. Secular books in this area almost always have a depressing side that is far too close to reality to be encouraging. Everything that is truly inspiring seems to have either a Christian or a Muslim twist. But even deeply religious children need an escape into an optimistic alternate reality, where someone they can relate to goes her own way and succeeds. During my childhood in the U.S., my brown self and my almost exclusively black friends yearned for something like that. So we ended up reading the same Tamora Pierce books all the white girls were reading, trying very hard to overlook the constant references to white aesthetics, because nothing written for kids like us was available.

Hutchinson points out how women choose to embed themselves in religious communities and (premature) family life, and how they are defined by their race. What I am missing here is something to connect the dots, namely a general critique of how group identities are forced upon minority women. From early childhood, we are indoctrinated to believe that our only source of personhood is the collective. While for young men, the question is “who do I want to be,” for minority girls it is always “which collectives do I want to be part of.” Mentoring rarely happens outside of a group context. Any place where a woman is allowed to build her identity is necessarily a very crowded place. Not being a huge fan of that particular TV series, but the phrase “assimilated into Borg slave drones” still comes to mind. I cannot recall a single moment during my adolescence when I was able to reflect on who this person should be. Instead, I was completely defined by my connections to others, by my social interactions, which were beyond my control. This was not because I wouldn’t have appreciated the opportunity to build my identity as an individual, who could then step out and be an agent in her community. Rather, I simply had no idea that option was even available to me – and it probably wasn’t. This is a serious impediment to female leadership, which by nature requires an established, independent personality. It relegates women to the role of community builders and organizers, who then make way for assertive male leaders. It makes us great social activists, and puts us at a serious disadvantage with respect to all other forms of leadership. To the point where I honestly have to say, it will be up to my daughter’s generation to overcome this obstacle, while it is too late for me.

There are a few other areas where Godless Americana remains superficial. In middle-class feminism, we find a divide between the sex-positive school and its opponents who criticize this school as unsuitable for minorities (Hutchinson takes this position). In reality, both of these schools are expressions of privilege, as both can apparently afford to concern themselves with female appearance, while offering nothing useful in terms of establishing female sexual agency. It is past time we left our convenient discourse over presentation and turned to the hard problem of agency. Self-determined women will produce a diversity of ever-evolving presentation styles. The book also names the acceptance of porn as a major catalyst behind an increase in sex trafficking, a pressing matter for my ethnic community. This feminist folk wisdom falls short of a useful analysis. Romani women were trafficked in increasing numbers long before the general population indulged in porn. As I have recently learned, the rise began in the countries of the former Eastern bloc at a time when pornography was outlawed and male-female interaction was still governed by pre-war etiquette. We will probably find useful explanations for sex trafficking in areas such as the tendency to define human relationships with woefully inadequate methods from business administration, and mass-culture induced dehumanization which amplifies older, race and sex/gender based dehumanization patterns, as well as the aforementioned breakdown of family structures in urban environments.

In my opinion, Godless Americana, like material produced also by Romani activists, is too quick to dismiss science as an instrument of liberation. It is difficult to see this without actual exposure to science, for example it was not apparent to me until I trained to become a lab technician. For a middle-class household, minority or otherwise, where plumbing services, convenience, safety gadgets, and so on, are only a phone call or an Internet order away, it is perfectly possible to live without any understanding of science. Its importance, however, rises exponentially with the scarcity of resources. Scientific knowledge makes the difference between successfully repairing a furnace, and the father and sole provider of a family of six receiving a fatal jolt. It prevents working-class minority households from taking out predatory loans to pay for “miracle cures” for fictional ailments. It makes the difference between manufacturing a babycam from discarded parts and losing a child. The difference between manufacturing items of personal hygiene, which are otherwise unaffordable, from cheap ingredients, and wasting away. Between knowing how to remove mold from your walls, and your children suffering adverse health effects. All of the above examples are from my own family, and I could name many more. Science is not a luxury for old white males. It is a vital necessity for disadvantaged communities which provides concrete remedies for immediate, real-world problems.

These points notwithstanding, Godless Americana is a must-read for non-believers and possibly even liberal believers of color. For many new skeptics, even from ethnic minorities, authors such as Richard Dawkins and Sam Harris are the beginning of Atheism. But whereas for white people they may also be the end of Atheism, People of Color have to go further. We cannot fight what we don’t understand, and this holds most especially for something as deeply entrenched as religion in minority environments. Sikivu Hutchinson does an amazing job shedding light on the unfortunate symbiosis between People of Color and religious institutions, which, by seemingly helping our communities, keeps them in a permanent state of dependency and docility.

___________________________________

Maryam Moosan-Clark is a Romani-American woman. She was born to a Muslim family in the Syrian-Turkish border region and raised in the United States. Maryam became a humanist in her early twenties and now lives in Switzerland with her husband and children.

2 Comments