Sunny Days?: Sesame Street, Prisons and the Politics of Justice

With Nelson Mandela’s funeral on the television, Sammy, who is 6, turned to me with a question that quickly grabbed my attention. Having already discussed his death, his activism, and apartheid, Sammy was very aware of Madiba’s struggles for justice. Listening to the commentators praise Mandela for his courage and beautiful spirit, he asked, “if he was so good, why would they put him in jail.” Inundated with messages that prisons are for bad people, he was clearly processing what felt like an incongruity of a heroic Mandela being locked up in a place that is suppose to be for bad people. This wasn’t the first time we’d engaged this topic, having pushed him to think about how PlayMobile imagines the world within its “police set,” which has police and robbers. We spent many minutes discussing why someone might steal and how such choices don’t inherently make someone a bad person. These conversations are never easy; they are messy and complex, which is made that much more difficult by the simplistic messages disseminated within kid’s culture. This past summer, I was hopeful when I learned that Sesame Street would shed light on the issue of mass incarceration.

Reflecting its history of engaging broader social realities (divorce, AIDS, death, perpetual war culture), Sesame Street broke the mainstream media’s relative silence regarding children of incarcerated parents in 2013. It introduces viewers to Alex, whose father is in jail. Upset by queries from friends about “where his Dad is,” Alex eventually tells the group that he’s in jail. Sofia notes that her dad was also “incarcerated” leading Abby Cadabby to ask, “what’s carcerate?” In response, she notes, “When someone breaks law, a grown-up rule, they have to go to prison or jail.” In another segment Murray and Nylo talk about the emotional difficulties of living with a family member in prison, emphasizing the importance of conversation and love. Another segment documents a little girl visiting her father, describing the bus ride, the rules, the sights, sounds, and emotional trauma of only getting to see a loved one within these conditions. Given the erasure of the impact of incarceration on families and the refusal to humanize those “made to disappear,” Sesame Street’s intervention is important.

The reaction to the Alex character was predicable; it highlights the importance of challenging dominant representations of prisons and incarcerated people and the dialects between America’s prison nation and its collective consciousness regarding those locked up. At the NY Daily News, this was but a few of the comments

-

Now it’s acceptable to have a parent in prison? Keeping the stigma fresh just might stop a younger generation from repeating the same mistake. Maybe in your culture it’s ok but I WANT my children to be afraid of that stigma. Sickening.

-

How about a muppet who[se] mom is a stripper….

-

Next is a character who[se] dad is away on jihad. She’ll be wearing a ski mask.

Huffington Post elicited the same sort of reactions

-

Sesame [S]treet is bending to the will and mindset of the urban peoples. “Oh, no honey, your daddy isn’t a bad man for being in prison. Only nice people go to prison” Instead they should teach the dangers of drugs, drug dealing, gangs, std’s, rape, pedos and anything else plaguing the inner city.

-

Here is all a child needs to know: if you commit a crime, you will go to jail. Jail is bad. Working or going to school is good. Don’t be bad like your mom or dad. They are in jail.

-

Did they explain the excuses people have for going to jail? Did they explain how it’s someone else’s fault that they broke the law and got caught?

At Fox News Insider, more of the same

-

When do we get a crack ho momma muppet?

-

Children need to be told people only go to prison if they did a bad thing , made the wrong choices!

-

It is not normal for your family to be in prison . No one should make it sound like it just happens, especially to children

While these comments reflects the misinformation, if not ignorance about prisons, alongside with racial stereotypes, they also embody the daily messages delivered that prisons house those who lack values, who lack morals, and those who have made bad choices; prisons are about safety and protection from the dangerous, from the undesirable, and from the pathological. This is the message kids (and adults) receive from a myriad of locations. Step into a preschool or elementary school, you will invariably see a group of kids playing a game that involves putting someone in jail – those who are bad are locked up. Go to a toy store, or turn on the television, and similar messages are delivered about criminality. Sesame Street sought to complicate this worldview by not only illustrating the number of families who are impacted by mass incarceration but its efforts to humanize people that are rendered as pariahs within the national imagination.

Unfortunately, Sesame Street chose not to include Alex in its regular episodes instead making the segment available in state and federal prisons within 10 states, as if prisoners needed to understand incarceration or the pain endured by their families, friends, and community. They also developed plans to distribute “half a million resource kits with DVDs featuring the character Alex, as well as advice and encouragement for kids and families dealing with an incarcerated family member.” While clearly an intervention against both the silencing and shame that undergirds mass incarceration, Sesame Street falls short in challenging our collective understanding of criminality. “I would like to see Alex on PBS,” noted Elizabeth Gaynes, who is the executive director of the Osborne Association. “It should be available not just for parents who have a kid in jail, but for kids who know somebody who does – because the stigma comes from other people.” Sesame Street not only failed to confront the stereotypes regarding incarcerated peoples, reinforcing the idea that criminals and law-breakers are one-in-the-same, but in its tepid distribution model it failed to challenge the ways that we all are impacted by mass incarceration.

In avoiding the controversy of making Alex a regular character that could teach all kids about prisons, in avoiding the politics of humanizing incarcerated people and their families, Sesame Street failed to disrupt the accepted logic that prisons house bad people. It failed to challenge the media and toy industry messages, the pedagogies of play, and the daily lessons that consistently depict prisoners as bad (not to mention dangerous, undesirable, threatening) in stark contrast to those good people who live freely among us.

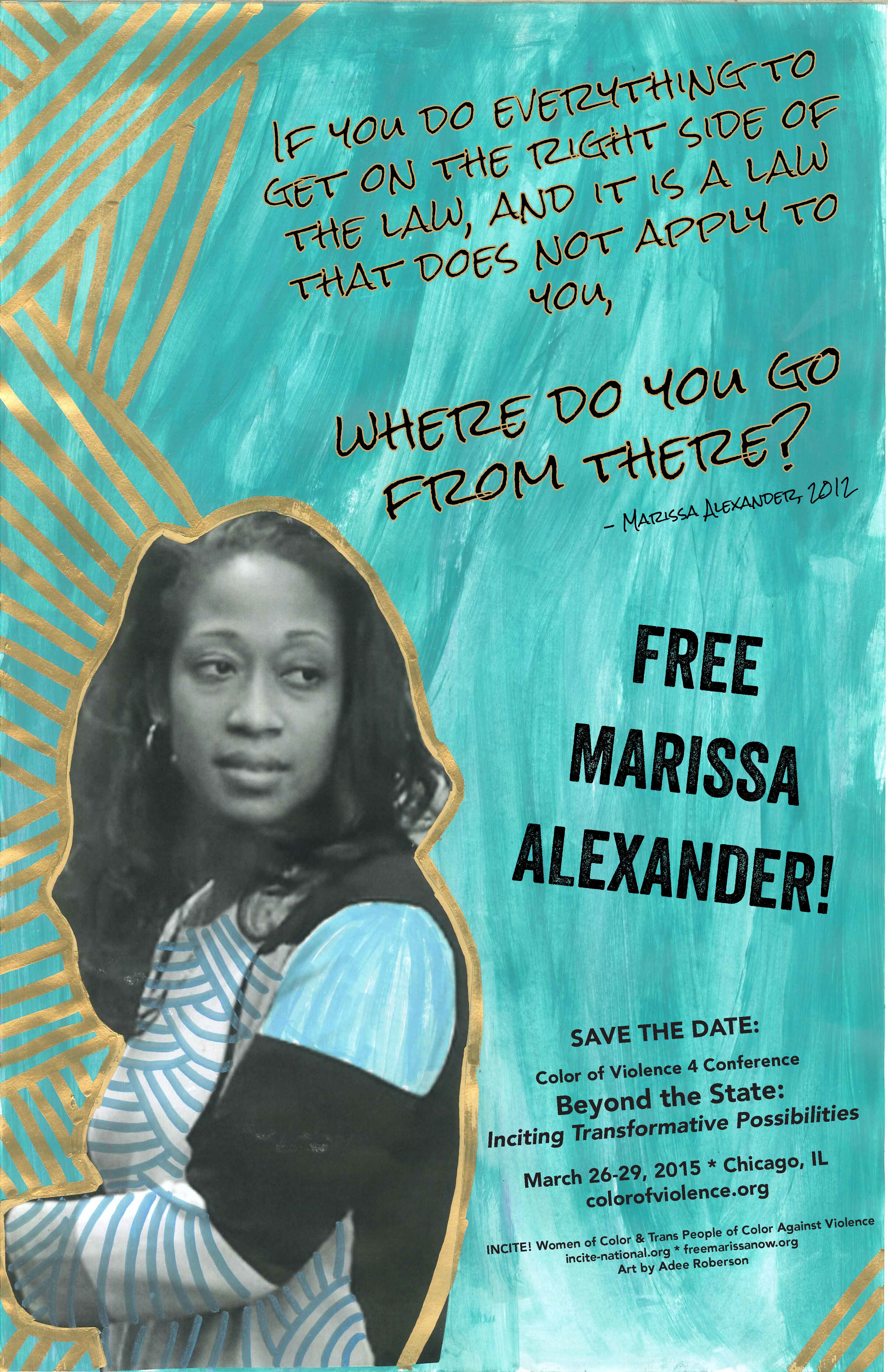

Reproducing the binary of “good” and “bad” people is a disservice to the struggle for justice and efforts to thwart the continued expansion of America’s prison system. Rather, we must demand images and narratives that acknowledge how people throughout society break laws – “grown-up rules” – yet not everyone is punished in the same way. We need to provide kids with the language to talk about inequality that contributes to mass incarceration, to talk about injustices that contribute. It’s not enough to talk about prisons, to use Alex to reflect on the difficulties facing the children and family of incarcerated people; we must talk about those whose parents are locked up, why some parents (and kids) are sent directly to prison while others are given “get out of jail free cards.”

Kids know the deal all too well. Evident in school, when some kids “get away with teasing” and or when Peter was punished more harshly than Wally even though they did the same thing, the lack of fair and equal treatment is a reality that resonates with children. When confronted with these conversations, it is crucial to push beyond the comforting worldview (at least to some) about justice and America’s prisons. It is important how people make mistakes, whether a friend pushing during recess, or someone breaking a “grown-up rule,” and that doesn’t mean they are bad. More than providing future generations for a language that moves beyond the binaries of good/bad, free/incarcerated, safety/criminal, these disruptions work to foster “freedom dreams” for all.

Several years ago, my father was sentenced to several months of home confinement; he also faced 5-years of probation. While I did not have to confront my ultimate fear – telling my kids why they wouldn’t see grandpa because – I still needed to tell them why he couldn’t leave the house at certain times or why we might not be able to take a family trip. This was hard because in discussing his situation, I needed to provide them with a language and understanding to think about prison not as a place for bad people. Challenging enough, I also continue need to remind them that part of the reason why grandpa did not go to prison is because of race and class privilege, because of the injustice of our criminal justice system. For us, this remains a work in progress, a task made that much more difficult by the messages they receive each and every day.

As you read this forum tweet – use #MumiaOnTFW — your thoughts. How can we best empower our kids, the next generation, to think of a world without mass incarceration; what strategies might we embrace to rethink justice, safety and security?

Get involved with the Free Mumia Movement

Visit the Bring Mumia Home website

Connect with the Bring Mumia Home campaign on twitter

Contribute to the “60 for Mumia’s 60th Birthday” Indiegogo campaign

Sign the petition to Free Mumia on change.org

0 comments