Re-imagining Black Power

By Nyle Fort

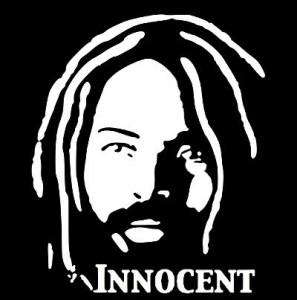

If Black Power were a play who would be its main characters? What would be its major themes? And what scenes would develop its drama? For most of my life when I thought of Black Power a flood of images came to mind: Stokley, Huey, George Jackson, Amiri Baraka, Attica, Watts, and pretty much all things “black,” “radical,” and, of course, male. Besides Assata Shakur and Angela Y. Davis, my imagination of Black Power wholly excluded women and their contributions to “the movement.” A couple of weeks ago that all changed. In the midst of research for a paper I’m writing on Mumia Abu-Jamal, a former Black Panther and current political prisoner, my imaginary black power “play” was interrupted, and then disrupted.

If Black Power were a play who would be its main characters? What would be its major themes? And what scenes would develop its drama? For most of my life when I thought of Black Power a flood of images came to mind: Stokley, Huey, George Jackson, Amiri Baraka, Attica, Watts, and pretty much all things “black,” “radical,” and, of course, male. Besides Assata Shakur and Angela Y. Davis, my imagination of Black Power wholly excluded women and their contributions to “the movement.” A couple of weeks ago that all changed. In the midst of research for a paper I’m writing on Mumia Abu-Jamal, a former Black Panther and current political prisoner, my imaginary black power “play” was interrupted, and then disrupted.

Abu-Jamal, well known for his radical journalism and revolutionary voice, is one of the few living survivors of Black Power iconicism. While many remember the fierce and flawed patriarchs of Black Power, few remember the (not so!) nameless women that transformed the popular mantra—“Black Power!”—into a powerful movement. In We Want Freedom: A Life in the Black Panther Party, Abu-Jamal does just that. Known more for his legal case than his intellectual contributions, Abu-Jamal is somewhat of a “living library” of Black Power movement history. Recognizing that history, however, is traditionally rendered as “his story,” Abu-Jamal reaches for an alternative history, or “herstory,” of Black Power.

In his chapter “A Woman’s Party,” Abu-Jamal narrates the gender politics of the Black Panther Party—a revolutionary vanguard of the black freedom struggle. Aware of mass media’s caricaturization of Black Power, Abu-Jamal challenges the dominant narrative framing Black Power, and by extension, the BPP, as hyper-sexist. According to Abu-Jamal, “The undeniable truth is that the Black Panther Party…gave the women of the BPP far more opportunities to lead and to influence the organization than any of its contemporaries.”[i] Recounting “Panther women” such as Afeni Shakur, Safiyah Bukhari, Elaine Brown, Audrea Jones, Frankye Adams, Ericka Huggins, and Naima Major, Abu-Jamal opines, “They were, without question, the very best of the Black Panther Party.”[ii]

Remembering Afeni, mother of the late Tupac Shakur, Abu-Jamal reminds us that her decision to join the movement was due to the way she felt women were treated. As Abu-Jamal explains, Afeni was attracted to the group because of Sekou Odinga’s and Lumumba Shakur’s behavior towards women. Ironically, it was gender politics—at least, initially—that led Afeni to join the BPP. Remembering Audrea Jones, founder of the Boston chapter, Abu-Jamal reminds us that women not only comprised, but also led, shaped, and co-created the movement. In short, women were not only present but also powerful and prophetic. Remembering Safiyah Bukhari, Abu-Jamal reminds us that it wasn’t only men who took up arms and fought. On the contrary, women like Safiyah, who commanded an armed unit of the Black Liberation Front, and Peaches, who fought alongside Geronimo Pratt in Southern California, were armed agents of their own liberation.

As Safiyah asserts, “Women in the Black Panther Party were working right alongside men, being assigned sections to organize just like men, and receiving the same training as men.”[iii] Remembering Ericka Huggins, falsely charged with conspiracy to murder, Abu-Jamal reminds us that “Panther women…were also [vulnerable] to the full force of State repression. The state was fully willing…to send such women to prison for the rest of their lives.”[iv] Recognizing that Black Power did not die with the dismantling of the BPP, Abu-Jamal also cites contemporary examples of Panther women who are continuing in the struggle for justice—women like Naima Major who founded Keep Ya’ Head Up foundation, a supportive collective of ex-Panther women.

Avoiding the allure of historical romanticization, Abu-Jamal reveals the beauty of Black Power as well as its messy elements and ugly expressions. Far from an apologist for sexism and patriarchy, Abu-Jamal admits, “Much of the movement was indeed deeply macho in orientation and treated women in many of these groups in a distinctly secondary and disrespectful fashion.”[v] Abu-Jamal has no illusory notions of an a-sexist, or even anti-sexist, Black Power orientation. Rather, Abu-Jamal historicizes the patriarchal posture of the movement when he states, “For men who, often for the first time in their lives, exercised extraordinary power over others, sexism became a tool of sexual dominance over subordinates.”[vi]

To be clear, Abu-Jamal does not offer an excuse for the sexism within the movement, but rather a historical explanation that both complicates and counters mass media’s images and imaginary of Black Power. According to Abu-Jamal, “It is with a focus on [its] macho and misogynist attitudes that much of the popular press has examined the role of Black women in the Black Panther Party.”[vii] While corporate media, in alignment with the federal government, attempts to sabotage our collective memory of one of Black America’s most revolutionary fractions, Abu-Jamal reminds us that the BPP—unlike the federal government and their media puppets—took a formal position on the liberation of women and the gay community: a move that historian Nikhil Singh considers “an astonishing leap, given the period.”[viii]

*****

To help FREE MUMIA please show your support at the links below:

Visit the Bring Mumia Home website.

Connect with the Bring Mumia Home campaign on twitter.

Contribute to the “60 for Mumia’s 60th Birthday” Indiegogo campaign.

Sign the petition to Free Mumia on change.org.

1 Mumia Abu-Jamal, We Want Freedom: A Life in the Black Panther Party (Cambridge, MA: South End Press, 2004) 173.

2 Ibid., 173.

3 Ibid., 180.

4 Ibid., 175.

5 Ibid., 160.

6 Ibid., 166.

7 Ibid., 160.

Pingback: Re-imagining Black Power | Moorbey'z Blog