COLLEGE FEMINISMS: Finding Black Feminism: A Revelation of Black Hair

By Ravon Ruffin

I recently had the opportunity to do an assignment that required me to articulate the ways in which Black Feminist Thought applies to my life experiences. Reflecting on my being as a Black woman, it became impossible not to discuss the intrusion that is my hair in American culture and politics. Regardless of the setting, interview, workplace, school, or outing amongst girlfriends, the common denominator seems to always be my hair. But more than that, it is Black hair.

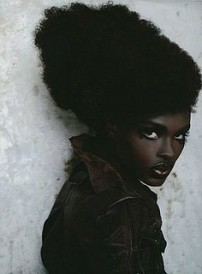

Black hair in all of its textures, shades, and lengths seems to intrinsically provoke a response to an often overlooked question: Why does Black hair matter? Our long history of subjugation has made the option of wearing natural hairstyles a form of resistance to previous oppressions. So, if Black hair can be called a form of resistance, can it then be a movement as well? Why not?

I am excited to see a new wave of feminisms on the rise, particularly for the women who have not had access to academic learning, or who might approach the “F” word somewhat timidly. Women of color across the globe are finding spaces to talk about their hair, be it through Facebook, Instagram, Tumblr, or websites dedicated to natural hair care. Still, although we’ve come a long way from the revolution, our hair remains a pertinent topic–out there.

Nevertheless, it’s also an avenue by which some women are finding their feminism.

Throughout my adolescence, I would change my hair quite frequently and without question. I quickly gained the fascination of my white counterparts in my predominantly white Catholic high school. I didn’t consider that my hair had the ability to make a statement to my constituents. It was just hair, like any other accessory to the body. At a time when I did not have language to articulate this peculiarity, I had the lyrics of India.Arie’s “I Am Not My Hair” (Testimony: Vol. 1, Life & Relationship, 2006) to advocate for the mere shared cultural experience of Black hair; sitting between mama’s knees with grease and hot combs.

I am not this skin, I am not your expectations, I am the soul that lives within.

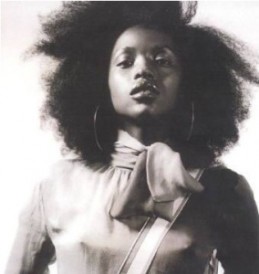

When I returned my hair to its natural state my freshman year of college, I realized the multitude of statements my hair could make (often times lost in translation). Since then, I have made use of various styles: locs, afros, braids, twists — each one rejecting the American standard of beauty for women. There’s always this concern about what my hair is doing from outside parties.

Black feminist scholar T. Denean Sharpley-Whiting tackles the positionality of women of color in hip-hop in her book Pimps Up, Ho’s Down: Hip Hop’s Hold on Young Black Women. Specifically, the chapter “‘I See the Same Ho’: Video Vixens, Beauty Culture, and Diasporic Sex Tourism,” critiques commercialized black beauty too often exploited in hip-hop and too often packaged in white American ideals of attractiveness. Nothing against my sistas with straight, long, or blonde hair. My problem is with prescription and circumscription. It seems that any appearance opposing this imagining requires explanation.

I prefer the words of Yaya DaCosta Johnson, 2004 season of America’s Next Top Model participant and finalist, considered limited by her naturally-textured hair throughout the competition:

I’m not Afrocentric, I’m just natural. But in this country women who don’t straighten their hair with chemical processing are stereotyped and labeled… Just because we don’t straighten our hair doesn’t mean we’re trying to be anything else–we’re being ourselves… Nobody asks Cassie, Ann or Amanda to be “less white.” I’m used to having to defend my very being…” (Sharpley-Whiting 29).

When scissors were raised higher than split ends, folks appeared out of the woods to condemn me for choosing to cut off “all that pretty hair” (translation: without my hair I’d no longer be desirable). I received the most backlash from older generations and men in my family. Fortunately, the progression of social networks were upward bound and many catered to natural hair forums. I had to search for sources of encouragement and positive self-imagery that were not readily available in mainstream media perceptions of beauty. My lighter complexion and long chemically straightened hair allowed me to pass, thus enabling me to be ethnically ambiguous with crossover appeal. No longer. Today, questions about my race are answered by thick, resistant, bountiful curls that sprout from my scalp.

Dacosta Johnson’s response is a lament over our hairs’ effortless power to raise Black consciousness. Through race consciousness, my natural hair journey became a spiritual one as I began to understand what being naturally me really meant. I had placed myself into a counterculture that didn’t feel it necessary to assimilate into normative representations of beauty. I often ask myself, Why did I feel that I had to have long straight hair to feel beautiful and what am I implying when I do not adhere? In no way am I demonizing those who choose to perm their hair. However, I think critical race consciousness requires that we contemplate how our existence is socialized and politicized. That is, when we “relax” our hair, who are we putting at ease? Ultimately, we should know our options and make informed choices–structured in personal standards rather than social needs, prescriptions and circumscriptions.

The fervor to reclaim the nappy even sparked recent media coverage when MSNBC correspondent Melissa Harris-Perry held a panel of notable black women titled “The Politics of Black Hair.” Harris-Perry often wears a variety of natural hairstyles herself. Perhaps this will prompt other women of color, specifically those in positions of power, to embrace their natural textures on screen and present alternative imagery to little black girls and women. We need a range of representations that embrace our many ways of being. Positive representations of less-altered black skin, hair, etc. are necessary. They provide a path toward love. The love of self and the love of black women.

My hair in many ways led me to Black Feminism and Black Feminism in turn gave me a choice to be myself. There is something revolutionary about that…

I claim this hair rooted in the struggles of Angela Davis, Assata Shakur, the struggle that is the black vote, the struggle that is freedom from all kinds of oppressions — the struggle — all struggles born from slavery. I claim this skin sometimes in shades of Mississippi mud imprinted by the trail of white henchmen, or the color of “I have a dream,” and my favorite shade, “Obama-Black-in-the-White-House.” I claim my right to speak my own narrative — from the kink to the curl, from the root to the end.

I am my hair and the skin that it embodies.

______________________________________________

Ravon Ruffin is currently a senior at Virginia Commonwealth University earning her B.S. in Anthropology and minoring in Religious Studies. She enjoys developing interdisciplinary discussions on studies of history, culture, and social practice. She strives to incorporate this discussion into the realm of museum studies, creating a space for open dialogue between the community and scholars. Ravon is a recently emerged Black Feminist, and hopes that through her work she can shed light on the holistic aims feminism has for all kind.

Ravon Ruffin is currently a senior at Virginia Commonwealth University earning her B.S. in Anthropology and minoring in Religious Studies. She enjoys developing interdisciplinary discussions on studies of history, culture, and social practice. She strives to incorporate this discussion into the realm of museum studies, creating a space for open dialogue between the community and scholars. Ravon is a recently emerged Black Feminist, and hopes that through her work she can shed light on the holistic aims feminism has for all kind.

Pingback: friday links | Fornicating Feminist

Pingback: friday links | Fornicating Feminist

Pingback: friday links | Fornicating Feminist

Pingback: friday links | Fornicating Feminist