“Somebody’s Children”: A Conversation with Laura Briggs

By Kelly Sharron and Abraham Weil

Laura Briggs is the chair of the Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies department at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. We had the opportunity to speak with her about her latest book, Somebody’s Children: The Politics of Transracial and Transnational Adoption, an interdisciplinary text that analyzes transracial and transnational adoption, both historically and in the present moment.

Somebody’s Children examines relations of power between sending and receiving countries, legacies of violence that have produced certain adoption flows, and the criminalization and stigmatization of some mothers and communities in relation to others. The title itself is a refutation of the invisibility of biological parents and ways power dynamics in adoption are often underrepresented (for instance, in Elizabeth Bartholet’s Nobody’s Children). Adoption is emblematic, Briggs argues, of the policing of mothers and families involved in the reorganization of the economy, State, and race in the second half of the twentieth century with the rise of neoliberalism and neoconservatism. The representational significance of children and families far exceeds the low number of adoptions. Briggs argues that the “symbolics of adoption and unwed pregnancy have done ground-clearing work for those who sought freer markets and less government” (12-3).

Briggs’ own experience with adoption was the impetus for her exploration of transracial and transnational adoption. Before adopting a child though the U.S. foster care system, Briggs researched extensively and quickly realized that engagements with the foster care system were not congruent with literature being produced at the time. Briggs found the majority of the literature unhelpful and as is so often the case, as an academic Briggs had stumbled across a new book project. In addition to publishing the book, she also maintains a blog titled Somebody’s Children.

Somebody’s Children follows three particular historical and social moments marked in the supply and demand of adoption, the geography of adoption, and the varying degrees of State intervention. The book is divided into three sections. The first deals with adoption in the United States, specifically tracing State intervention in the private sphere of Black, Native, and welfare-receiving mothers and families. The second takes on transnational adoption in Latin America with covert, often violent, U.S. intervention and the increasingly open markets (and with it, the privatization of adoption). The third section focuses on contemporary reproductive politics in the case of gay and lesbian adoptive parents as well as immigrant mothers and the “threat” they pose to the U.S. nation state.

Chapter One focuses on the racial politics of Black adoption and placement. Dating to slavery, the separation of Black families has been a tactic utilized by the state as a means to control Black labor supplies. Briggs shows how this legacy has continued in the politics of adoption demonstrating the ways in which Black families (and single Black mothers in particular) have been labeled “unfit” to parent, especially in the context of the welfare system and the unattained ideals of liberal individualism. Briggs also discusses the response of the National Association of Black Social Workers; the NABSW resisted Black children being raised in white families and targeted the adoption system for reform.

Chapter Two discusses the history of forced removal of Native American children from their tribes and lands. Briggs traces the practice historically to compulsory boarding schools, where there was continuous government intervention in the raising (and attempted assimilation) of Native children. Briggs describes the adoption of Native children by white families as “social genocide” (80) as communities were left with collective trauma after mass numbers of children were taken away. Briggs details the Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978 (ICWA), which served as a response to this history of removal and established a strong preference for Native foster children to be placed in Native homes.

Chapter Two discusses the history of forced removal of Native American children from their tribes and lands. Briggs traces the practice historically to compulsory boarding schools, where there was continuous government intervention in the raising (and attempted assimilation) of Native children. Briggs describes the adoption of Native children by white families as “social genocide” (80) as communities were left with collective trauma after mass numbers of children were taken away. Briggs details the Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978 (ICWA), which served as a response to this history of removal and established a strong preference for Native foster children to be placed in Native homes.

We asked Briggs about recommendations for reforming institutionalized policies that support the systematic removal of children of color from their parents. Briggs reminds us to think critically about the current case of Adoptive Couple vs. Baby Veronica, which was recently heard by the Supreme Court after being postponed for a significant amount of time. Of the case, Briggs says:

“The facts are actually quite clear. The child has a dad who was eligible for enrollment as Cherokee and the Cherokee nation has challenged the adoption and the State Court in South Carolina agreed unambiguously that the child was an Indian child and deserved to be treated as such under the Indian Child Welfare Act. I think we are seeing a political pushback against ICWA and other protections for birth families that is quite explicit on the part of Evangelical Christian groups that are seeking to make more and more children available for adoption. Some of these groups will say that they see children of single mothers as orphans. I want us to be aware that the politics of what children are available for adoption are heating up because there’s a large and growing ‘demand’ in the United States at the same time that policy protections for birth families and communities are growing. So ‘due process’ gets read by some as ‘bureaucracy.’ Transnational adoption in particular is currently experiencing a sharp decline because of the kinds of protections that were put together in 2008 with the Hague Convention on Intercountry Adoption that provide minimal due process rights for families. I think we are going to see a continued assault on due process protections and I think there is a lot at stake for the politics of family and what constitutes of family; we need to be concerned about this.”

Chapter Three discusses trends in criminalization of single mothers and the changing demographics of adoption across lines of race and class. Reagan-era neoliberalism produced distinct trends in the adoption market. Middle-class women stayed in the workforce later in life and thus delayed childbearing, producing a crisis of systemic infertility and changing the face of adoption to the “desperate infertile couple” (97). Reagan also placed blame on unmarried women for society’s ills, justifying retraction of the welfare state. “Crack mothers” became emblematic of this problem, highlighting the intersections of racialized medicalization and criminalization. The effects of cocaine during pregnancy were exaggerated–women were tested for the presence of narcotics and put in jail moments after giving birth. Aimed at mothers of color, this process led to an increase in the number of black children in foster care and the child welfare system. Similarly, Native mothers were targeted after a growing concern over fetal alcohol syndrome. The divergent trends of targeting certain communities for the removal of children and the middle-class demand for adopted children created an adoption supply and demand laden with power relations and economic privilege. As a result, private adoptions increased outside the purview of federal regulation and involved coercive structures and large fees.

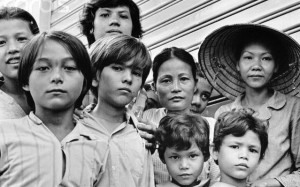

Photo credit: Fold3

Part II of Somebody’s Children turns to transnational adoption, specifically in Latin America. Chapter Four discusses trends in adoption markets produced by the Cold War. As part of general interventionist sentiments, the U.S. and private companies began to separate children from birth families under the guise of Christianity and “saving” children from the influences of communism. Briggs shows that the Vietnam War also highlighted ways in which U.S. intervention abroad implicated children of mixed race as embodiments of the French and U.S. presence in the region. Photographs of half-American children in the streets of Vietnam spread feelings of guilt among Americans while also characterizing Vietnamese mothers as incapable. These children were taken “away from a land that didn’t want them” as they were put up for stranger adoption in the U.S. (157). Photography, guilt, and neoliberal intervention allowed for shifts from anti-immigration to sponsoring to international adoption.

Chapter Five explores Latin America and U.S. interventions during conflict in the region. As a broader scheme of promoting U.S. interests and free markets in Latin America, international adoption became part of these ideologies as it produced “a renewed sense of American responsibility for those outside its borders and an easing of the movement of money and (some) people” (160). The disappearing of children became a way to eliminate the next generation of resistance; State Department terminology became another political tool, as the shifting of categories from “refugees” to “orphans” became a means to eliminate the politics of home countries in consideration of visas. Chapter Six looks to present-day Guatemala and the attitudes towards Guatemalan values as well as the ability of Guatemalans to raise their own children. Briggs observes three trends that facilitated transnational adoption: the spread of Christian-right family morals, the lack of a distinct nuclear family in indigenous raising of children, and the denial of allegations of criminality surrounding adoption during and after the war.

Part III brings together themes from throughout the text by opening up contemporary U.S. debates about adoption, specifically gay and lesbian couples arguing for inclusion within recognizable family structures (marriage included). The move for inclusion and rights-based claims to adoption has been primarily based on financial resources as well as the marginalization of certain communities as unfit to care for their children. Briggs argues that gay and lesbian couples have aided these processes of neoliberalism by providing a “safety valve” for the State to take children from communities of color, define them as “hard to place,” and then pass them off to gays and lesbians, thereby providing an alternative to the civilian welfare state (242). Her bold claims are refreshing for readers as she demonstrates how class became the most important factor in deciding if a family was fit to raise a child, allowing middle-class gay and lesbian parents to be depathologized and adopt children of color, HIV-positive, and other “hard to place” children, unburdening the state and facilitating neoliberal flows of capital.

We asked Briggs what role LGBT groups (such as HRC), focused on rights-based claims for adoption, play in furthering problems in transracial and transnational processes. The answer was clear: “Rights is the wrong language for adoption; nobody has the ‘right’ to adopt.” Briggs reminds us that LGBT folks have had many experiences with the loss of children and encourages the community to be critical of employing the same rhetoric of “rights”; that far from being an expansive language of freedom, they have often served as road blocks in creating household dynamics outside of hegemonic constructions of “the family.” Briggs makes clear that LGBT folks have much at stake in this debate and should remain alert and aware as we advance policy involving transracial and transnational adoption.

The book has many successful moments, and a plethora of take-away points. Briggs hopes to highlight that “adoption is not always a win-win for both parties,” which is often the rhetorical appeal to well-intentioned adopting parents. Additionally, Briggs wants readers to think about the political sphere and political economies in which adoption processes take place. Briggs says, “Adoption is also a political process about wars on communities of color. In particular, I want people to remember that one of the responses to the resistance of the Black freedom movement has been a pushback in terms of separating moms from their kids. Similarly, the Native resistance movement has been met with taking kids away. So this not a neutral and ambiguous process, but is in many instances quite political and deliberate.”

Why should readers of The Feminist Wire care about Somebody’s Children? “The book is written in part to show how racism and imperialism are carried out through reproductive politics,” Briggs notes, adding that “there has been a struggle between feminists who write about adoption–between those who think we should be talking about a right to adoption and those of us who believe adoption is not a right, that adoption is not a reproductive right akin to other reproductive rights.” Locating Somebody’s Children in the latter genealogy, Briggs says, “There is other work that locates itself in the feminist tradition that discounts the existence and experience of birth mothers and birth families. I think that is a dangerous move that excludes a lot of what feminists need to know about the circulation of children.”

Briggs closes the books with important questions that intentionally remain open. In our discussion with Briggs, we asked what the next step in this debate will be. Briggs is currently working on a book entitled All Politics are Reproductive Politics that considers two previous projects to attend to the ways “reproductive politics infuse every arena of the political, from questions of empire to questions of race to questions of immigration.” Drawing on issues such as labor, immigration, welfare reform, and gay marriage, Briggs will show how deeply embedded these processes are in reproductive politics.

Briggs closes the books with important questions that intentionally remain open. In our discussion with Briggs, we asked what the next step in this debate will be. Briggs is currently working on a book entitled All Politics are Reproductive Politics that considers two previous projects to attend to the ways “reproductive politics infuse every arena of the political, from questions of empire to questions of race to questions of immigration.” Drawing on issues such as labor, immigration, welfare reform, and gay marriage, Briggs will show how deeply embedded these processes are in reproductive politics.

In Somebody’s Children, Briggs covers a large swath, both geographically and historically. This feminist book ties together themes of neoliberalism, capitalism, and family structure as they relate to adoption and closes with politically relevant questions for activists and scholars alike.

[Briggs, Laura. 2012. Somebody’s Children: The Politics of Transracial and Transnational Adoption. Durham, NC: Duke Univesity Press. 376 pages.]

_______________________________________________

Kelly Sharron is a first-year Ph.D student in Gender and Women’s Studies at the University of Arizona. Previously, Kelly graduated summa cum laude with a BA in Gender, Women, and Sexuality Studies and Political Science from the University of Minnesota- Twin Cities. Her primary research focus is queer political organizing in post/colonial nations, particularly in southern Africa. Other research interests include transnational feminisms, queer theory, and feminist political theory.

Kelly Sharron is a first-year Ph.D student in Gender and Women’s Studies at the University of Arizona. Previously, Kelly graduated summa cum laude with a BA in Gender, Women, and Sexuality Studies and Political Science from the University of Minnesota- Twin Cities. Her primary research focus is queer political organizing in post/colonial nations, particularly in southern Africa. Other research interests include transnational feminisms, queer theory, and feminist political theory.

Abraham Weil is a first-year Ph.D student in Gender and Women’s Studies whose research focuses on gender, queer sexualities; radical feminisms; postcolonial studies; and theories of assemblage and affect. Previously, Abe completed a MA in Gender Studies at Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey and an individualized BA at the University of Redlands, incorporating Gender Studies, Philosophy, Race and Ethnic Studies, and Film.

Abraham Weil is a first-year Ph.D student in Gender and Women’s Studies whose research focuses on gender, queer sexualities; radical feminisms; postcolonial studies; and theories of assemblage and affect. Previously, Abe completed a MA in Gender Studies at Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey and an individualized BA at the University of Redlands, incorporating Gender Studies, Philosophy, Race and Ethnic Studies, and Film.

0 comments