Rage against the patriarchy, Dr. Nikita Levy, and the devaluation of black women

By j.n. salters

I was compelled to complain because I feel that the vast majority of black folks who are subjected daily to forms of racial harassment have accepted this as one of the social conditions of our life in white supremacist patriarchy that we cannot change. This acceptance is a form of complicity…. Racial hatred is real. And it is humanizing to be able to resist it with militant rage. –bell hooks

From the founding of the nation, the meaning of American citizenship has rested on the denial of citizenship to blacks living within its borders. –Dorothy Roberts

I write this essay so that I do not have to swallow the rage—or to borrow from bell hooks, “killing rage”…“militant rage”…“rage at injustice”…“constructive healing rage”—that currently consumes me regarding the state of black women in society. I write this essay after learning that none of my friends, family members, colleagues, or undoubtedly most of America have come across any news coverage or informal conversations discussing the events that transpired two months ago involving a doctor accused of illegally and nonconsensually videotaping and photographing possibly over one thousand patients—mostly women of color—during their medical procedures. I am not only angry at the black doctor who used his power, position, and race to gain illicit access to the bodies of these women, but also at the media and our white supremacist society for its insistent racism, sexism, and classism that allow such exploits to take place and then get downplayed or overlooked. While this is only one story tied to a multi-century-long narrative of devaluation, this racialized, gendered, and classed incident, as well as its lack of publicity, speaks to both the historical and contemporary devaluation of women of color, the ways in which we are denied normative expectations of privacy, and our lack of full citizenship in the United States. As Linda Gordon explains in Pitied But Not Entitled: Single Mothers and the History of Welfare, “Without some minimum level of security, well-being, and dignity, people cannot function as citizens.”

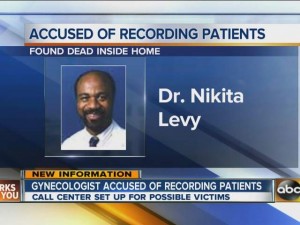

On February 4, 2013, the late Dr. Nikita Levy, a Jamaican-born obstetrician/ gynecologist who worked at Johns Hopkins’ East Baltimore Medical Center—a center that primarily serves low-income African-American women—was accused of secretly recording patients during exams. An employee reported the doctor to hospital officials after becoming suspicious of a pen that Levy would consistently wear around his neck while examining patients. Hospital security later interviewed Levy in his office, where they found additional devices, and according to an official statement released by Johns Hopkins Medicine, “determined that Dr. Levy had been illegally and without our knowledge, photographing his patients and possibly others with his personal photographic and video equipment and storing those images electronically.”

On February 4, 2013, the late Dr. Nikita Levy, a Jamaican-born obstetrician/ gynecologist who worked at Johns Hopkins’ East Baltimore Medical Center—a center that primarily serves low-income African-American women—was accused of secretly recording patients during exams. An employee reported the doctor to hospital officials after becoming suspicious of a pen that Levy would consistently wear around his neck while examining patients. Hospital security later interviewed Levy in his office, where they found additional devices, and according to an official statement released by Johns Hopkins Medicine, “determined that Dr. Levy had been illegally and without our knowledge, photographing his patients and possibly others with his personal photographic and video equipment and storing those images electronically.”

Johns Hopkins alerted the Baltimore City Police Department, who reportedly executed several search warrants and obtained an “extraordinary” amount of evidence against Levy. Courthouse News Services reports that law enforcement officers discovered “computer equipment containing thousands of photographs and videos of his patients and their genitals and/or other private areas of their anatomy.” The photographs and videos “had been taken surreptitiously by Dr. Levy during much, if not all of his more than twenty years as a physician with Johns Hopkins” and patients are concerned that “personal and private photographs and/or videos of their bodies” have been “distributed over the Internet or by other means.” Police also found multiple cameras in at least one examination room, according to Baltimore police spokesman Anthony Guglielmi. “There are multiple multimedia videos and photographs on servers and hard drives,” Guglielmi tells The Washington Post. “We just don’t know how many. We envision there are a lot … We think the victim pool could be quite large.”

On February 8, Levy’s patients received a letter from Hopkins officials stating that Levy “is no longer working for Johns Hopkins and seeing patients” and “to ensure the continuity of your care, please contact us so that we may, as quickly as possible, review any urgent care needs, reschedule any existing appointments, and help you find a new clinician.” Complying with requests from the Baltimore City Police Department, Hopkins officials did not disclose any details of the case so that the investigation “would not be compromised.” It was not until February 18 (two weeks after Levy was outed), after Levy, 54, committed suicide in his Towson home, that Hopkins issued a public statement and sent a letter to Levy’s patients informing them that their naked, vulnerable bodies had been recorded without their consent—continuing a long history of dehumanization, fetishization, nonconsensual invasions, and objectification.

A portion of the public statement reads:

Any invasion of patient privacy is intolerable. Words cannot express how deeply sorry we are for every patient whose privacy may have been violated … Dr. Levy’s behavior violates Johns Hopkins code of conduct and privacy policies and is against everything for which Johns Hopkins Medicine stands … We regard our patients’ right to privacy and professionalism as fundamental and foundational.

Notice that the word “privacy” is used four times, once in each sentence—accentuating Johns Hopkins Hospital’s sincere “intolerance” of patient privacy invasions. Nevertheless, I am not convinced. Levy’s minimal punishment (he was terminated and offered counseling), hospital protocol that enabled Levy to get away with these illegal, intrusive acts for such an extended time period (possibly over twenty years), and the public statement issued on February 26, suggest otherwise. This statement reads:

Currently, images and videos taken by Dr. Levy are securely in the possession of the Baltimore City Police Department. Except for a few individuals who have been notified, we also do not know whether any of Dr. Levy’s patients are identifiable in any video or image contained in that evidence. If the Baltimore City Police Department determines that images or videos are identifiable, we pledge that we will continue to cooperate fully with the Baltimore City Police Department and Baltimore City State’s Attorney’s office to assist them in identifying those individuals.

In order for police to “determine” if images and videos are “identifiable,” officers must gawk at thousands of recordings and photographs of these women in their most vulnerable states, revictimizing them and exacerbating their humiliation and embarrassment. One must wonder: Are the hospital and police department doing all that they can to ensure the least amount of distress and additional privacy invasions of Levy’s former patients? Like many of their slave ancestors who were sexually, physically, and emotionally abused by their masters, will these women merely become overlooked minor characters within a multi-century-long narrative of devaluation and nonconsensual invasion?

Since slavery, black women in America have been denied the reasonable expectations of privacy afforded to other citizens. From their rape and forced pregnancy by slave-owners — for both pleasure and profit — to their naked brown bodies being flaunted on auction blocks to be sold to the highest bidder, black women have lacked privacy since first arriving in America. Such privacy violations have become markers of black women’s exclusion from civil society, as well as their devaluation within “the black community.” While slavery has “legally” ended, the invasions of privacy experienced by Dr. Nikita Levy’s patients serve as reminders that black women still lack full citizenship in the United States. Similar to Sara Baartman (dubbed “The Hottentot Venus”)—the young South African woman who was exhibited seminaked as a “freak” throughout Europe in the early 1800s to entertain audiences with her large buttocks and elongated labia, and upon her untimely death, dissected and put on display at the Musée de l´Homme—black women continue to be exploited, degraded, and both hypervisibilized and invisibilized, and fetishized.

After centuries of degradation, Sara Baartman’s remains were returned to her homeland in 2002, and she was finally laid to rest in South Africa’s Eastern Cape on August 9, 2002, South Africa’s National Women’s Day—a burial and commemoration that served a political agenda of reconciliation and nation building in post-apartheid South Africa. I wonder if and how long it will take Johns Hopkins to redress Levy’s transgressions? If the hospital will do more than merely attempt to “assure” Levy’s former patients with “ongoing care of the highest quality”? If these women will ever feel “safe” (again) behind the closed doors of an examination room? If their photos and videos are being circulated, mocked, and fetishized at the police station, in the homes of strangers, and on medical fetish porn websites? I wonder if and how all of these victims are expressing their rage? And, I wonder if women of color will ever be afforded reasonable expectations of privacy and other rights of citizenship?

On March 2, 2013, The Baltimore Sun reported that over 2,000 people claiming to have been Levy’s patients have contacted Baltimore police with information, questions, and concerns. Several of Levy’s patients have filed lawsuits against Levy’s estate and Johns Hopkins, and according to Courthouse News Services, these patients are seeking:

…class certification, compensatory and punitive damages for invasion of privacy, lack of informed consent, intentional infliction of emotional distress, negligence, violations of Maryland visual surveillance laws, and costs of therapy and counseling. They also want Johns Hopkins to find and destroy all photographs and videos made of Levy’s patients, to notify all potential victims, and to prevent exploitation of patients.

In April 2012, St. Francis Hospital in Hartford, Connecticut, and its insurers, settled for over $50 million with 150 known child victims of hospital endocrinologist George Reardon, who launched what he claimed was a “long-term pediatric growth study” as a pretext to abuse children while posing them for obscene photos. Unfortunately, according to experts, claims of privacy breaches in the Levy case may be a bit more complex, hinging on whether Levy’s patients can be identified in the images and what the images show. Like Baartman, Levy’s victims must endure additional dissection and humiliation before any of their suffering can be rectified, although their distress will never completely dissipate.

From my state of rage, which enabled me to write this article, I urge others to join in unleashing a productive rage that can potentially inspire action on behalf of Levy’s victims, and more generally against our “white supremacist capitalist patriarchal culture.” It is with this “collective black rage,” in the words of bell hooks, that “renewed, organized black liberation struggle” will happen. “Progressive black activists must show how we take that rage and move it beyond fruitless scapegoating of any group,” hooks writes in her essay, “Killing Rage: Militant Resistance,” “linking it instead to a passion for freedom and justice that illuminates, heals, and makes redemptive struggle possible.”

*I would like to thank legal scholar, feminist, and privacy law expert Anita L. Allen, who first informed me of the details of the case.

_______________________________________

j.n .salters is a doctoral student at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania interested in the intersections of race, gender, class, and sexuality in rights to privacy, black cultural production, identity politics, sex work, law and criminal justice, and visual culture.

j.n .salters is a doctoral student at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania interested in the intersections of race, gender, class, and sexuality in rights to privacy, black cultural production, identity politics, sex work, law and criminal justice, and visual culture.

20 Comments