Feminists We Love: Liora K

Liora K is an Arizona photographer who produces art not only for work and pleasure, but also for Feminism. When I first discovered Liora’s provocative and powerful images, it was in the context of her feminist project featuring text written on women’s nude bodies. My collaborator (Soraya Chemaly) and I were looking for images to add to our site-in-progress on reproductive politics, and when we came across one of Liora’s photographs, we were immediately struck by the bold beauty and political fearlessness of her work. We selected one and contacted the artist. I received the licensing agreement via email, and only then did I learn that Liora lived in Tucson. She is frequently out and about in our community, participating in many artistic and political activities, including the “Turns Out I’m Human” exhibit. A young, unabashedly feminist woman using her talent and passion in the service of meaningful work and politics locally and beyond–what’s not to love?

TFW: Tell us a bit about yourself.

Liora: I was born in 1988 and raised in a small town in northern New Jersey. I was raised as a conservative Jew, and went to public school and Hebrew Sunday school through the 12th grade. I was an excellent reader, but a horrible speller. High school was marked by a close group of nerdy friends who enjoyed each other’s company and were serious choir nerds. I met my now-fiancé in my senior year, and we had a long distance relationship across the country throughout college.

I graduated magna cum laude from Ursinus College with a BA in Fine Arts (focus in Photography) in 2010. My photography mentor was Donald Camp – I learned so much from him about what it means to be passionate about the art one makes. He wasn’t the only amazing and influential professor I had there, but our one-on-one classes are without a doubt some of my favorite memories from college. In my college career, I worked in pinhole, film, and digital photographic media, sometimes combining these with origami concepts and sculptures.

After I graduated, I moved to Arizona to be with my partner. I worked a variety of jobs while doing photography on the side. I love fashion photography, portraiture, and working in macro. Tucson is not necessarily a place I expected to end up, but since I have been here I have grown as a photographer and as a person, for which I am exceedingly grateful.

TFW: You describe yourself as a feminist, a term that many young women seem to have no truck with. Can you talk about what being a feminist means to you? How would you define your feminist politics and ways of life? How does your feminism impact your work, commitments, and movement in the world?

TFW: You describe yourself as a feminist, a term that many young women seem to have no truck with. Can you talk about what being a feminist means to you? How would you define your feminist politics and ways of life? How does your feminism impact your work, commitments, and movement in the world?

Liora: I’m a feminist because I can’t live in a world where I am defined, limited, and categorized by my genitalia, where women are objectified beyond reason, where rape culture thrives, and where these injustices (and more) are so blatantly ignored and denied by so many people.

I believe in the power of intersectional feminism. Even though I still have a lot to learn, I think that by going together, we can go far. I do my best to incorporate as many different aspects of women’s struggles in my work – I want everyone to see themselves in my photographs. The oppression and dehumanization of women affects everyone, and I strongly desire to represent that.

Part of making that happen is being open to the idea that I will always have something to learn – that a detail, a concept, an idea, will always be a mystery to me. This is both frustrating and incredibly motivating. This project has not only helped me to express my anger towards the amount of power that patriarchy wields, but has been an incredible vehicle to understanding parts of feminism that I hadn’t previously been conscious of. As a result, I am so much more aware of what I am being taught by media and privilege, and how to try to circumvent that conditioning to achieve greater equality.

TFW: Can you talk about some feminist role models in your life, people who have shaped your worldview and politics?

Instantly three people come to mind: my mom, my dad, and my college adviser, Dr. Colette Trout.

My parents always taught me that the only thing that could limit me was myself, and that while inequality between the sexes existed, I should never think that my gender could hold me back from achieving my goals. I read constantly growing up, and they encouraged this by providing magazines and books that had positive female role models (such as New Moon, a feminist publication for young girls). They were, and are, honest, enthusiastic, and supportive. They also encouraged me from a young age to be independent and actively voice my opinions, which is how, when I was 16, I ended up at the March for Women’s Lives in Washington D.C. with my mother, sister, aunt, cousin, and a few friends – it was an absolutely amazing and life-changing experience to be in one place with more than one million other feminists. I thank my parents sincerely for giving me a home in which I could grow up with confidence in myself as a person and also as a woman conscious of the world she lives in.

In college, I was fortunate enough to be paired up with Dr. Colette Trout as my academic adviser. Beyond being an amazing and motivating professor, she was, and continues to be, an inspiration to be bold, work hard, and think critically and creatively. In my senior year of college I was took her class on “Rebels, Villains and Criminals in French and Francophone Literature.” It was toward the end of this class that Dr. Trout recommended that I read Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex, (in French, of course), and helped me understand some of the more difficult passages. Reading the text was an incredible eye-opener for me, and with Dr. Trout’s guidance I felt as though I was able to absorb, reflect, and truly learn from it. Throughout my college career, Dr. Trout was always there with an encouraging word or a pondering question. She taught me that feminism is not only about advancement, but also about consideration, careful thought, and critical application. I am extremely grateful for her guidance and confidence in me.

Learning about Second Wave feminism provided much-needed context for my upbringing in the Third Wave. It helped me to understand how I believe what I believe and solidify some personal truths: namely, that a victory for one group of women is not a victory for all women. That our equality depends on our ability to communicate openly and honestly. That we will never reach our goals without reaching out to each other. And finally, that without united, inclusive, and critical action, we will forfeit what we have left.

TFW: As a photographer, you’re clearly interested in documentary images and using your work to advance social justice. Can you talk about the relationship between art and work, technique and politics? Why and how does photography work for you as a medium for seeking change?

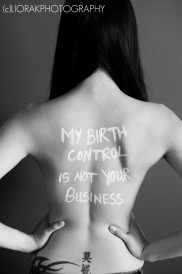

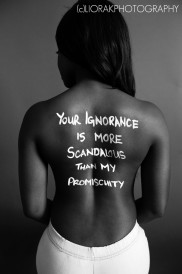

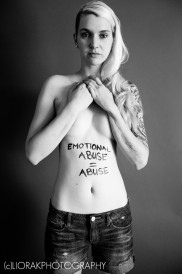

Liora: Last March, when I started witnessing all the attacks on birth control, abortion rights, equal pay, and retractions of protections for survivors of domestic violence, I wanted to see an artistic response. I have seen and studied art that has acted as great catalyst for change – and what we need is a great change. I wanted to create a body of share-able and instantly understandable work that people could connect with and use to continue to spread the word: “women’s rights are being sabotaged, but we are fighting back.”

Liora: Last March, when I started witnessing all the attacks on birth control, abortion rights, equal pay, and retractions of protections for survivors of domestic violence, I wanted to see an artistic response. I have seen and studied art that has acted as great catalyst for change – and what we need is a great change. I wanted to create a body of share-able and instantly understandable work that people could connect with and use to continue to spread the word: “women’s rights are being sabotaged, but we are fighting back.”

I am not an excellent verbal communicator. I have a tendency to lose my words. Most of the time when I try to communicate ideas I end up using hand motions, sounds, and gibberish-sounding words to express the feeling of a situation instead of waiting for the perfect descriptive sentences. Many of the phrases I use in my project are from a list that was a product of much advance thinking.

Art has always been a communicative force for me. Drawing, painting, dance, photography – each of these things helps me to share my thoughts in a way that is authentic to me. When I discovered photography at age 18, it fit. I was able to produce my thoughts in the way that I thought them. My photographs are direct translations of my thought process, unhampered by lost words. In this way, I find photography to be ideal for me as a way to seek change.

TFW: Many women are hypervisible in our culture while others remain invisible. And the visibility often has much to do with race, class, body size, ability, geography, and other structural locations/identities. How do you think about or address this in your work?

Liora: Right from the beginning it was very important to me to represent as many different types of feminists as possible. I wanted all types of people to see themselves reflected in the project – to feel and be a part of it. To find participants, I reach out via casting calls online, personal networks, and volunteers who happen to see the project and want to be a part of it. Provided that I have time, any volunteer can participate, though I do try to make sure that what is shared online is a diverse representation of all the shoots that I do. I’m constantly evaluating the body of work to see who may be underrepresented, and reading comments online to see who others believe are underrepresented. Currently my studio is not accessible to wheelchairs, though I am working on solutions for that. I’m also looking for women and men over 30 to participate!

TFW: You photograph women in all kinds of settings: fashion shoots, weddings, studio feminism. I’d love to hear you talk about differences and commonalities among these settings. For example, do you think of your fashion and wedding shoots as feminist?

Liora: Everything a person does is marked by his or her personal experiences, beliefs, and creeds. In this way, while feminism is not necessarily the focus behind my fashion and event photography, I can certainly see how it influences all of my work.

Many wedding photographers work within the constraints of the wedding industrial complex; brides are photographed like idyllic young virgins and grooms like powerful providers. There’s a very specific power dynamic, and generally a prescribed formula to the day. While I certainly am inspired by other wedding photographers, my approach is less to dictate how a couple should be photographed, and instead give as little direction as possible so I can photograph the couple as authentically as I can. Also, I tend towards feminist, funky, and offbeat clients – and I love them!

I love fashion photography. To me, it is all about the weird, the push, and the play. It’s about combining so many creative people and seeing how far everyone can go. It can have deep meaning, it can be pure aesthetic space, or it can be a combination of those two. Something I don’t love about it though, is the amount of body-morphing Photoshop that takes place, and the emphasis on looking a particular way. I love photographing models of all sizes, and do not participate in body morphing post processing. I find it to be an unnecessary and detrimental practice. This could stem from my feminism, but I think I stay in a more creative and productive headspace when I don’t concentrate on what my subject needs to “fix.”

Additionally, and similarly to weddings, there are many power dynamics at work in the fashion industry that relay between designers, hair and makeup artists, photographers, editors, models, agents, and event producers. I have heard horror stories about other “professionals” in the industry using their power to manipulate and abuse models who are too young or too shocked to know how to react. I support the right to pursue a creative career safely and with dignity, and work hard to encourage trust between me and the people I work with. This trust creates a space for experimentation and expression – I photograph the whole person, not just the external beauty. Again, as with weddings, I value authenticity in my photographs – even the ones that are abstract, or more purely aesthetic.

TFW: You have a section on your website called “Play.” Feminists are frequently branded as being humorless, lacking a sense of play. How do you think about play in relation to work, politics, and being human?

Liora: If I were to have a personal definition of the verb “to play,” it would read something like the following:

Play: (v) To enjoy making mistakes, to make some intentionally, and to find joy through them.

Playing with ideas is an extremely important part of my personal artistic process – it allows me to work through mental blocks, experiment with beauty, attempt new techniques, and explore avenues that sometimes make me uncomfortable. When I am finding joy through error, I think I am at my most open to learning – I think I am at my most human. I am, occasionally, also at my most frustrated.

An important part of playing is forgiving yourself for the mistakes that don’t work. It’s an exercise in constant and necessary paradigm shift. In discovering more about feminism, I have discovered more about myself, and sometimes there are things I don’t like. The ability to forgive myself for my mistakes so that I can make room for new perspectives has been one of the most beneficial things about pursuing this project and continuing activism

TFW: Talk to us about body image, an issue you obviously care deeply about.

Liora: I love working with bodies. Maybe it stems from taking live art classes through high school, but there is just something so unique, textural, and interesting about bodies. I find that a lot of my playing orchestrates itself around bodies covered in different materials, such as glitter, newspaper, paint, and sometimes just light.

Working with many nude people has shown me how vastly different body landscapes are. I don’t believe I have seen any body that even remotely reminds me of another – and each is beautiful.

Advertising relies on my beliefs that a) my body is imperfect, and b) I need to change it to be more perfect. This is how things are sold. I don’t think that bodily perfection exists or should exist. There is no possible way that human perfection exists – though there are infinite ways that human beauty exists.

When I work with a subject I have to fall in love with their body. I want to find the small beauties – the way a shadow trespasses on a collarbone, or the way a shoulder rotates, or perhaps even the way a scar works its way through and around muscle. It pains me to hear subjects critique themselves about their imperfections – I wish they could see themselves as I see them. When asked, I tell them that I won’t Photoshop their bodies to be different then what they are. There is nothing to be fixed.

TFW: What is it like for you to be a young feminist photographer working in one of the most repressive states in the nation? How is your work both “local” (i.e., about Arizona) and not?

Liora: Living in Arizona spurred the whole feminist project. When I started the project a year ago, I was so full of anger and so frustrated. Creating and publishing the photos online was such an immense release, and the positive and negative responses really created an incentive to continue.

Almost every participant in the project has been an Arizonan. For me, this makes it a very local project talking about very global issues. We are widely recognized for the rampant misogyny in our politics and general culture, and I am very proud this project can expose that there are Arizonans who are not afraid to loudly and publicly demand change.

TFW: Is there anything else we should know about you?

Liora: One of the most common criticisms directed at my project is “Why all the nudity?” Many online commenters find it offensive; they accuse me of exploiting women’s sexualities, and then using their bodies to spread a message. They say that the images are counterproductive; if I want to empower women, I’ll photograph women who are fully clothed.

Liora: One of the most common criticisms directed at my project is “Why all the nudity?” Many online commenters find it offensive; they accuse me of exploiting women’s sexualities, and then using their bodies to spread a message. They say that the images are counterproductive; if I want to empower women, I’ll photograph women who are fully clothed.

I would never use nudity as a way to spread a message. I would, and do, use nudity in my artwork. It’s not accidental. I love photographing bodies. I find them all beautiful, and I find that nude bodies evoke a sense of connection among humans in a way that clothed bodies don’t.

In this project, nudity represents two things. Not only does it shows how close and paralyzing these issues are to women, it also shows vulnerability. I also find that the nudity took on a second meaning of its own. Women are taught that our bodies hold all our value; thus, we have to keep them clothed, protected, and hidden.

I cherish the freedom I do have – to create this work safely, without fear of legal or religious repercussions. The worst I have gotten is people yelling at and threatening me on the Internet. Another artist in another place might be risking her life to do this kind of work.

But even in the U.S., women are punished – legally and socially – for ‘giving it away,’ for ‘being easy,’ for ‘showing too much.’ For us, showing our bodies is an act of defiance, a revealing of truths. The painted phrases are truths – that there is no excuse for rape, that women have heartbeats, that people have a right to plan. And we – both photographer and participants – are revealing them together.

8 Comments