#eulogizingaretha: From a Daughter Whose Mother Loved Aretha

By Idrissa Simmonds

There is a generation of Black girls born at a time when our mothers spoke the name Aretha in the house with the regularity and familiarity of a favored family member. I am firmly in the seat of this generation. Right now, if I sit still long enough, I can see my mother, her back to me as she peels carrots at the kitchen sink, belting out R-E-S-P-E-C-T in her deliciously off-key voice. The movement of her shoulders and the shift of her hips is enough for me as a child to know that those lyrics, that song, sung by a woman named Aretha whose voice can be likened to God’s tambourine itself, fueled my mother’s soul with a touch of power.

Aretha’s voice is written into the very foundation of my mother’s life, etched into every wall of her. The woman who formed me was formed by Aretha and I imagine that this is why her loss is both a personal sting and a collective moaning.

My mother was born and raised in Brooklyn and I grew up in Vancouver, Canada – it was Aretha’s voice coming through my mother’s record player, filling our Surrey home with Black Detroit and the American South, which built my early understandings of motherhood as a revolutionary, radical practice. It was her voice that reminded me that Black women from all corners of the diaspora are valuable, necessary, and fierce. I did not have the language, but Aretha served as my sonic introduction to womanism.

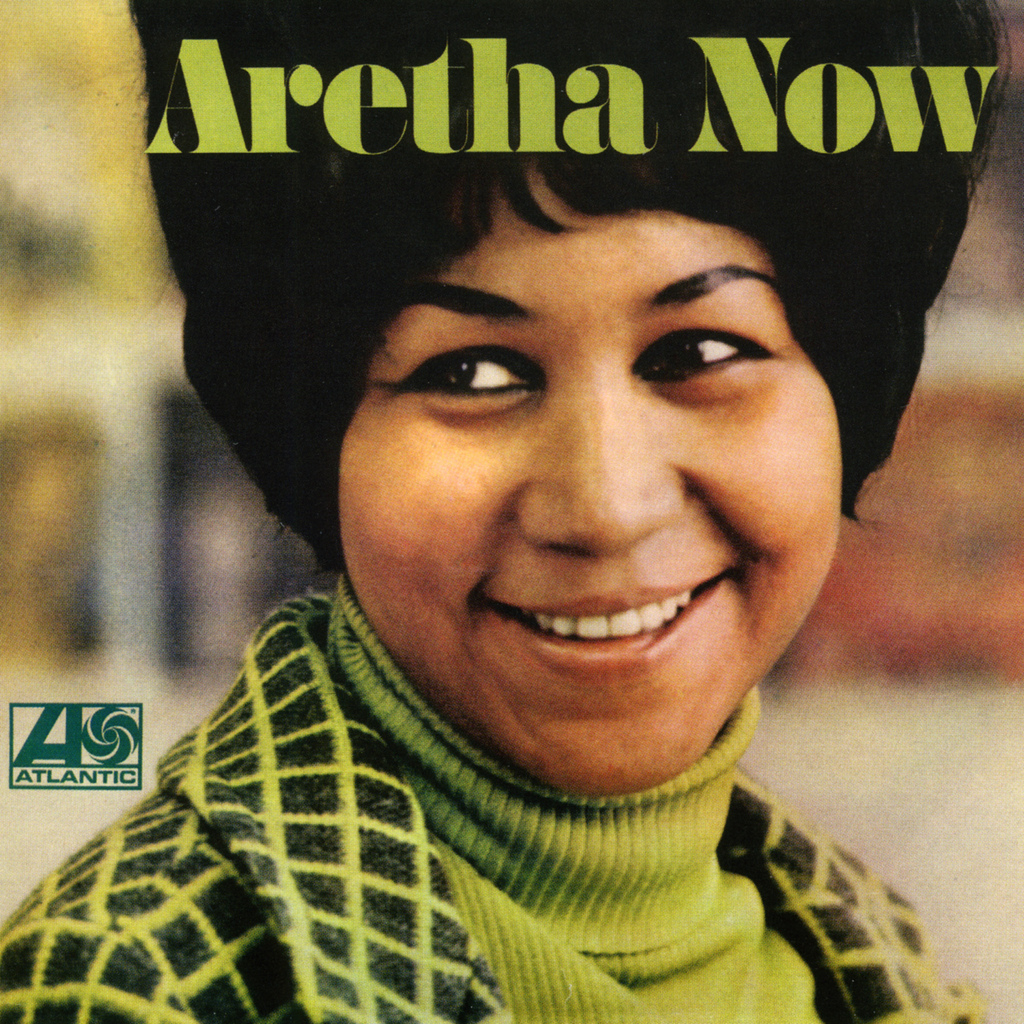

Aretha was a fully formed vocal genius in childhood. She was equipped with a flawless ear, and an ability to innovate and expand any existing song into her own. Her Mississippi-born, Detroit-bred existence buries every barked word, every stereotype, every sharp critique against Black women. She commanded every audience she stood before to look and see the beauty of child-rearing, working, excelling, cooking, and being in a black woman’s body. Her presence at the top of the charts was a form of validation that reverberated in the lives of black women from Brooklyn to Detroit to Tennessee to Toronto.

My mother passed of cancer four months prior to Aretha’s transition. These losses are endings that still cause me to buckle with grief every time I think of my mother’s laugh, and how her body would bloom a little at the sound of Aretha’s voice through the stereo. But these losses are also openings, doorways that my sisters and I walk through because my mother, Queen Aretha, and the other Black women of their generation dared enough to fly high in the midst of all that sought to bring them to the ground. Aretha, as spirit, as an ancestor, is unstoppable.

We will not see the likes of her again and I am just grateful, grateful, to have borne witness to what she unlocked for my mother.

Idrissa Simmonds is a writer, poet, and facilitator. She centers her work in the field of education on uplifting and amplifying the voices, experiences, and leadership of leaders of color and those of other underrepresented backgrounds. She is co-editor of the anthology Black Girl Magic (Haymarket Books) alongside Mahogany L. Browne and Jamila Woods. Her recent publications include Poetry Magazine, Room Magazine, Black Renaissance Noire, and The Caribbean Writer. She is an MFA candidate in fiction at Warren Wilson College.

Idrissa Simmonds is a writer, poet, and facilitator. She centers her work in the field of education on uplifting and amplifying the voices, experiences, and leadership of leaders of color and those of other underrepresented backgrounds. She is co-editor of the anthology Black Girl Magic (Haymarket Books) alongside Mahogany L. Browne and Jamila Woods. Her recent publications include Poetry Magazine, Room Magazine, Black Renaissance Noire, and The Caribbean Writer. She is an MFA candidate in fiction at Warren Wilson College.

0 comments