Personal Is Political: Coming Home

By Soumitree Gupta

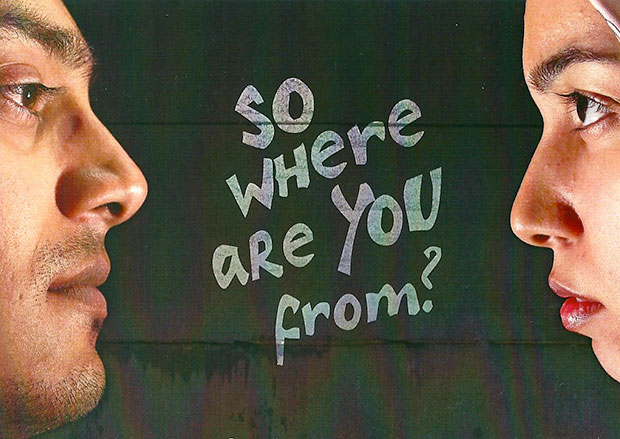

This piece is a response to all those occasions when I’ve been asked the “home” question—where I’m from—and I’ve struggled to condense the multiple genealogies that I call home into one pithy response.

This piece is a response to all those occasions when I’ve been asked the “home” question—where I’m from—and I’ve struggled to condense the multiple genealogies that I call home into one pithy response.

As a diasporic South Asian woman who comes from a migrant family, I locate myself in multiple homes. Coming home, for me, signifies multiple origins and crossings, multiple departures and arrivals, as well as belonging to multiple places and communities. Coming home also means feeling displaced and disoriented sometimes. Coming home means routinely negotiating purist, linear, and originary scripts of home and identity. These narratives have variously labeled me as an outsider, stranger, foreigner and other, or have imposed the role of “native informant” on me, or have accused me of being unfaithful to my “roots.” Coming home means situating myself within my multiple, complex genealogies of border crossing, which in turn have shaped my multiple, hybrid identities.

I have a home in Montana where the morning comes unrushed—and sometimes unpredictably with a sudden dip in temperature in early fall or an unexpected snow shower in late spring—while I rush through my banal morning routines to get ready for work. Coming home to Helena, Montana signifies new beginnings, and building friendships and communities over shared ideals, experiences, and commitment to teaching and social justice. I also have a home in the “Silicon” valley in California where the bougie dreams of people living in gated communities, buying SUVs and big houses with lush green lawns thrive alongside the vibrant and continuing legacies of social justice movements. Coming home to California makes me feel disoriented and rejuvenated, hopeless and hopeful. I used to have a home in Syracuse in upstate New York, where I spent almost seven years forging personal, intellectual, and activist connections over fragments of conversation—sometimes left unfinished and then picked up—in the classroom, outside of the classroom, in my faculty mentors’ offices, in the hallway, in the library, on the sidewalk, and at potluck dinners with friends as we sat huddled together by the fireside through the cold winter evenings. While the world outside died little by little, we spoke animatedly about our personal histories and collective dreams. Returning to Syracuse feels like coming home.

Coming home to all of these places and memories also means leaving my mother behind: my mother who had once aspired to do what I do now—teach and write, my mother who was forced to stifle her intellectual aspirations and fully embrace a domestic life so she could focus on raising her two children, my mother who taught me to read and love literature, my mother who sprang to my rescue like a fierce tigress every time my paternal uncle’s wife body-shamed me, my mother who taught me to be a feminist years before I was introduced to textbook definitions of feminism in college, my mother who has silently supported me despite our many disagreements and fights over my world views and life choices. Coming home means getting comfortable with the silence on the other end of the telephone line when my mother runs out of topics but doesn’t want to disconnect.

Coming home also means grappling with my familial genealogies of migration and trauma. I grew up listening to my maternal grandmother ritualistically recount her experience of being forcibly displaced from her home in Dhaka (now in Bangladesh), and then migrating to Calcutta (now in India) as a refugee on the eve of the 1947 Partition. The year 1947 marked the end of two hundred years of British colonization in South Asia, but this formal decolonization was to be accompanied by the partition of South Asia into India and Pakistan (now Pakistan and Bangladesh) along religious lines. Partition led to violent mass migrations, including sectarian and sexual violence, displacement, deaths, and unending brutalities unleashed on men, women, and children on both sides of the newly created India-Pakistan border. About fifteen million people migrated, and about one million civilians lost their lives during Partition. Yet, the lived experiences of these communities that were impacted by Partition constitute a much-silenced chapter in South Asian and global history. My maternal grandmother’s story is part of this repressed communal memory. Her trauma is part of a collective trauma.

Coming home also means grappling with my familial genealogies of migration and trauma. I grew up listening to my maternal grandmother ritualistically recount her experience of being forcibly displaced from her home in Dhaka (now in Bangladesh), and then migrating to Calcutta (now in India) as a refugee on the eve of the 1947 Partition. The year 1947 marked the end of two hundred years of British colonization in South Asia, but this formal decolonization was to be accompanied by the partition of South Asia into India and Pakistan (now Pakistan and Bangladesh) along religious lines. Partition led to violent mass migrations, including sectarian and sexual violence, displacement, deaths, and unending brutalities unleashed on men, women, and children on both sides of the newly created India-Pakistan border. About fifteen million people migrated, and about one million civilians lost their lives during Partition. Yet, the lived experiences of these communities that were impacted by Partition constitute a much-silenced chapter in South Asian and global history. My maternal grandmother’s story is part of this repressed communal memory. Her trauma is part of a collective trauma.

My teenage grandmother lost her beloved father to an unexpected illness just before the Partition plans were announced. My grandmother’s father was an ardent supporter of her education; he used to motivate my grandmother to dream big and pursue higher education so she could be independent. In my grandmother’s testimony of Partition, the personal and the political merge as she ritualistically recounts memories of a blissful, prosperous familial life and Hindu-Muslim harmony in her community before Partition, along with memories of unexpectedly losing her father, home, and community on the eve of Partition. Her testimony also recounts her forced migration to Calcutta along with her mother and two younger siblings and their everyday struggles as uprooted refugees in post-Partition Calcutta, which in turn impacted my grandmother’s education and precipitated her early marriage. My grandmother was just a few months away from taking her matriculation exam, which would qualify her for entering college, when she migrated to Calcutta. Despite numerous constraints because of Partition turmoil, she took the exam in Calcutta, passed it with flying colors, and even received a scholarship that would cover the expenses of her college education. Yet, she was forced to give up her intellectual aspirations because of her precarious circumstances. The accommodation that her mother had found in Calcutta was tenuous. My great grandmother didn’t have any source of income other than depending on her capricious elder son in Calcutta to support her family. Under these precarious circumstances, my great grandmother worried about the possibility of being homeless again. She worried especially about her only daughter’s safety in case they would be out on the streets. She thought that getting her daughter—my grandmother—married would perhaps ensure the latter a safe home. However, contrary to my great grandmother’s expectations, marriage didn’t solve anything. After marriage, my grandmother had to move in with her husband’s extended patriarchal family that unsurprisingly didn’t allow her to pursue her college education. Instead, my grandmother was sucked into the daily vortex of an unhappy marriage and mundane domestic routines. She did eventually resume and successfully complete her college education years after she got married, but she never had the intellectual life that her father dreamed for her. My grandmother’s lived memories of Partition and its repercussions, as well as her and my mother’s unfulfilled intellectual lives, have defined my identity and intellectual trajectory.

While both my grandmother and I identify as migrant women, our migration stories are markedly different. Unlike my grandmother, I had a choice to migrate to the U.S. because my class privilege allows me to cross borders, to leave and arrive at multiple homes at my will. Yet, because of my gendered and racial locations, my coming home to these multiple places and genealogies also involves my coming to terms with experiences of being dislocated, marginalized, othered, silenced, and rendered expendable. I cannot dissociate home from the painful and sometimes traumatic memories of being subjected to staring, groping, whistling, catcalling, body shaming, and body policing—on streets, at airports, in public transports, at the workplace, in grocery stores, at the DMV office, at the doctor’s clinic, and within intimate familial and communal spaces. Because I wore something or I didn’t wear something. Because I said something or didn’t say something. Because I did something or didn’t do something. Because I challenged someone’s perception of the normal. Because I am a woman. Because I am brown.

Coming home, for me, means constantly negotiating these embodied experiences of belonging and un-belonging across multiple geographies and trauma-temporalities. Coming home means coming to terms with my multiple, fraught genealogies of border crossing, and forging a shared space of friendship and solidarity with anti-racist, anti-capitalist, anti-imperialist, and queer feminist allies in this journey.

Soumitree Gupta is an Assistant Professor of English at Carroll College, Montana. She has a PhD in English and a Certificate of Advanced Study in Women’s Studies from Syracuse University. Her teaching and research interests span postcolonial studies, gender studies, transnational studies, diaspora studies, comparative race and ethnic studies, and trauma and memory studies. In particular, her research focuses on feminist/proto-feminist representations of the mobile woman, home, and nation in diasporic South Asian fiction, memoir, and cinema. She traces the genealogies of her intellectual interests to both her mother’s and her maternal grandmother’s lived experiences as women.

Soumitree Gupta is an Assistant Professor of English at Carroll College, Montana. She has a PhD in English and a Certificate of Advanced Study in Women’s Studies from Syracuse University. Her teaching and research interests span postcolonial studies, gender studies, transnational studies, diaspora studies, comparative race and ethnic studies, and trauma and memory studies. In particular, her research focuses on feminist/proto-feminist representations of the mobile woman, home, and nation in diasporic South Asian fiction, memoir, and cinema. She traces the genealogies of her intellectual interests to both her mother’s and her maternal grandmother’s lived experiences as women.

0 comments