June Jordan’s Songs of Palestine and Lebanon

By Therese Saliba

I write beside the rainy sky

Tonight an unexpected an

American

Cease-fire to the burning day

that worked like war across my

empty throat before I thought to try

this way

to say I think we can: I think we

can.

–June Jordan, “To Sing a Song of Palestine”

For Arab feminists of my generation, June Jordan brought us out of our invisibility. She embodied transnational feminist solidarity long before it was in vogue. This bold Black woman, this brilliant poet, never retreated from speaking unspeakable truths. She visited Palestinian refugee camps after the massacre of Sabra and Shatilla in 1982. She returned to Lebanon after Israel’s massacre of refugees at a UN camp at Qana in 1996. Jordan turned the most gruesome horrors in our world—the world of Arab isolation and unabated imperial violence–into searing poems and essays that spoke to our shared humanity across the boundaries of race, class, creed and culture, and across oceans of ignorance and incomprehensibility. She shared Arabic coffee with those in mourning, bore witness to the strangulation of Israeli occupation and the US-sponsored arsenal of death, and through her writing tied our suffering to the terrors of anti-Black racism and police violence in the US. She affirmed our collective struggle, our resistance and resilience with a resounding “I think we can” (1985, 45-6).

Jordan was one of the first African American feminists to show her solidarity by traveling to Lebanon, producing haunting poetry that trenchantly indicted the US government and its citizens for the violence there. In “Apologies to All the People in Lebanon,” she lets her own complicity, as an American taxpayer, stand for the whole people: “I didn’t know and nobody told me and what/could I do or say, anyway?” After a litany of official excuses, and gruesome details of slaughter, she concludes, “Yes I did know it was the money I earned as a poet that/paid/for the bombs and the planes and the tanks/that they used to massacre your family. . . I’m sorry. I really am sorry” (1985, 106). This scathingly satirical piece exposes the excuses, the failure of recognition and solidarity, the emptiness of apology in the face of this brutally executed invasion.

Jordan was one of the first African American feminists to show her solidarity by traveling to Lebanon, producing haunting poetry that trenchantly indicted the US government and its citizens for the violence there. In “Apologies to All the People in Lebanon,” she lets her own complicity, as an American taxpayer, stand for the whole people: “I didn’t know and nobody told me and what/could I do or say, anyway?” After a litany of official excuses, and gruesome details of slaughter, she concludes, “Yes I did know it was the money I earned as a poet that/paid/for the bombs and the planes and the tanks/that they used to massacre your family. . . I’m sorry. I really am sorry” (1985, 106). This scathingly satirical piece exposes the excuses, the failure of recognition and solidarity, the emptiness of apology in the face of this brutally executed invasion.

Jordan’s subsequent travels to Lebanon allow her to probe this question of solidarity more deeply. Her poem “Moving Towards Home” (1985, 132-34) repeats a list-like elegy to the horrors she witnessed in Sabra and Shatilla camps. Beginning each line with “I do not wish to speak about . . . Nor do I wish to speak about. . .” she then does speak of bulldozers burying the dead whose arms and legs stick out of red dirt, of “nightlong screams,” of families forced to watch the murder of children and spouses. Significantly, Jordan uses a negative construct to expose the mechanisms of silencing, even as she bears witness to these “unspeakable events.” The poem turns from these silencings to impugning the logic of genocidal exclusion and the sanitized discourse that attempts to cover over the horrific violence that assaults our collective humanity. The poem turns again on “[her] need to speak about living room” and her “need to talk about home.” Here, Jordan insists on a need for normalcy, as represented by the living room—this need for room to live—with its bitterly ironic implications of the German Lebensraum left as an indictment. Jordan concludes with her now famous lines:

I was born a Black woman

and now

I am become a Palestinian

Against the relentless laughter of evil

There is less and less living room

And where are my loved ones?

It is time to make our way home.

Jordan elides her marginalization as a Black woman and her identification with the Palestinians, then highlights her privileged connection to those making “our” way home, while others’ lives and homes have been destroyed. In this process of becoming other, the lines between I/Palestinian, my/our merge in collective grief, moving toward a kind of home in the world

Jordan came to believe that it was not misinformation that perpetuated the slaughter in Lebanon, but rather racist dehumanization: “The problem was that the Lebanese people, in general, and the Palestinian people, in particular, are not whitemen: They never have been whitemen. Hence they were and they are only Arabs, or terrorists, or animals. Certainly they were not men and women and children; certainly they were not human beings with rights remotely comparable to the rights of whitemen, the rights of a nation of whitemen” (2002, 191). In “Eyewitness from Lebanon” (1996), she wrote: “I went to Lebanon because I believe that Arab peoples and Arab Americans occupy the lowest, the most reviled spot in the racist mind of America. I went because I believe that to be Muslim and Arab is to be a people subject to the most uninhibited, lethal bullying possible.”

Jordan also understood that to speak of Palestine was “the ultimate taboo, a taboo behind which the fate of entire people, the Palestinians, might be erased” (2002, 193). In the face of vicious charges of anti-Semitism, and “the awesome determination by whitemen in this country, to silence or to discredit American dissent,” Jordan is left wondering what life after Lebanon would be like (193). Early on, Jordan identified “the seemingly irreconcilable” divisions within feminist and leftist communities, between “those for whom Israel remained a sacrosanct subject exempt from rational discussion and dispute,” and “those to whom Israel looked a whole lot like yet another country run by whitemen whose militarism tended to produce racist consequences. . .” (193). “Life after Lebanon” (1985) signals a turning point—for Jordan, and for all writers. She saw the silencing of debate as an affront to the intellectual and moral life of our country. For this, Jordan—like so many others (Arabs, Jews and other allies)–experienced smears, censorship, and distortions of her words. It is in large measure for this price she paid so willingly that we today owe a debt to Jordan and her insistent voice, clearing the way for those who followed.

Jordan also understood that to speak of Palestine was “the ultimate taboo, a taboo behind which the fate of entire people, the Palestinians, might be erased” (2002, 193). In the face of vicious charges of anti-Semitism, and “the awesome determination by whitemen in this country, to silence or to discredit American dissent,” Jordan is left wondering what life after Lebanon would be like (193). Early on, Jordan identified “the seemingly irreconcilable” divisions within feminist and leftist communities, between “those for whom Israel remained a sacrosanct subject exempt from rational discussion and dispute,” and “those to whom Israel looked a whole lot like yet another country run by whitemen whose militarism tended to produce racist consequences. . .” (193). “Life after Lebanon” (1985) signals a turning point—for Jordan, and for all writers. She saw the silencing of debate as an affront to the intellectual and moral life of our country. For this, Jordan—like so many others (Arabs, Jews and other allies)–experienced smears, censorship, and distortions of her words. It is in large measure for this price she paid so willingly that we today owe a debt to Jordan and her insistent voice, clearing the way for those who followed.

Jordan never shied away from naming the unspeakable and breaking the silences that fester between us. For Jordan, those silences centered on her “gay rights” or bisexuality, and on Palestine—issues she saw as the most silenced in US society (A Place of Rage, 1991). As feminists, we have all felt these explosive spaces, the exchanges “requiring acrobatics of self-denial” (1981, 182). Jordan reminded us that those silences must be spoken or exploded, despite censorship, bullying, endangered friendships. She reminded us back in the early 1980s that it wasn’t just Lebanon that was engaged in a so-called “Civil War”, but that there was a deep history and ongoing White/Black confrontation in our own country that looked a lot like civil war.

She insisted on drawing clear analogies between anti-Arab racism and the resonant history of anti-Black racism that Americans more readily comprehend. And her words were prophetic about the unabated, yet largely accepted violence against Arabs and Muslims that was to ensue under the guise of “The Global War on Terror.”

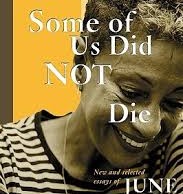

In the wake of 9/11, and months before her own death, Jordan wrote the introduction to her final collection, Some of Us Did Not Die (2002). Her piercing critique of American complicity, the security state under the guise of democracy, and her celebration of resistance resonate with her earlier writings. I carry her songs of resilience in my head, and wonder what she would be writing today, after Israel’s massacres in Lebanon (2006), and Gaza (2009, 2014); after the destruction left by the American invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq. And today with the unabated killings of Black men and women, I carry her words from “Poem about Police Violence” (1974): “What you think would happen if/ every time that they killed a black boy, then we killed a cop.” A simple yet searing question that cuts to heart of racism and power and state violence. Jordan’s words and activism were visionary; in speaking unapologetic, piercing truths and drawing connections across struggles, she was ahead of her time. Today a video circulates, When I see them, I see us—a montage of poetry and images juxtaposing the anti-Black violence and the violence of Israel occupation, with statements of Black-Palestinian Solidarity—this is one of Jordan’s legacies.

In the wake of 9/11, and months before her own death, Jordan wrote the introduction to her final collection, Some of Us Did Not Die (2002). Her piercing critique of American complicity, the security state under the guise of democracy, and her celebration of resistance resonate with her earlier writings. I carry her songs of resilience in my head, and wonder what she would be writing today, after Israel’s massacres in Lebanon (2006), and Gaza (2009, 2014); after the destruction left by the American invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq. And today with the unabated killings of Black men and women, I carry her words from “Poem about Police Violence” (1974): “What you think would happen if/ every time that they killed a black boy, then we killed a cop.” A simple yet searing question that cuts to heart of racism and power and state violence. Jordan’s words and activism were visionary; in speaking unapologetic, piercing truths and drawing connections across struggles, she was ahead of her time. Today a video circulates, When I see them, I see us—a montage of poetry and images juxtaposing the anti-Black violence and the violence of Israel occupation, with statements of Black-Palestinian Solidarity—this is one of Jordan’s legacies.

In “Civil Wars” (1981) Jordan recounts how the activist community gathers in the wake of yet another crisis and enacts rituals of polite behavior. She critiques how “the courtesies of order. . . pursued from a heart of rage or terror or grief. . . defuse and deform the motivating truth of critical human response to pain” (179). June sat in our living rooms after the worst massacres, expressed those unspeakable atrocities, and the grief, terror and rage in our hearts. She never deformed our truths with niceties. She recognized “At the end of this century massacre/remains invisible unless the victim/skin reads white” (1985, 127). She found strength in the steadfastness of the Lebanese cedar, in Palestinian resistance. She called us family. This is my song to June Jordan, who did not die, for as she wrote, “My life seems to be an increasing revelation of the intimate face of universal struggle” (1981, xi). That intimate face—Black, Arab, queer, Nicaraguan, South African, Cuban, Palestinian, Lebanese, woman—lives on in her words.

Bibliography

Civil Wars: Selected Essays, 1963-80 (Boston: Beacon Press, 1981), ix-xii, 178-186.

“Eye Witness in Lebanon,” The Progressive (August 1996), 13.

Living Room: New Poems, 1980-1984 (New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press, 1985), 45-46, 104-106, 127, 132-134.

“Life After Lebanon” in Some of Us Did Not Die: New and Selected Essays of June Jordan (New York: Basic/Civitas Books, 2002), 187-195.

Therese Saliba is faculty of Third World feminist studies at Evergreen State College, Washington, and former Fulbright scholar in Palestine. She is co-editor of Gender, Politics and Islam (2002) and Intersections: Gender, Nation and Community in Arab Women’s Novels (2002). Her essays have appeared in Arab & Arab American Feminisms, Arabs in America, Food for Our Grandmothers, and other collections and journals. Saliba is on the advisory board of the online Brill Encyclopedia of Women and Islamic Cultures and Gaza Mental Health Foundation, and works locally with the Rachel Corrie Foundation for Peace & Justice.

Therese Saliba is faculty of Third World feminist studies at Evergreen State College, Washington, and former Fulbright scholar in Palestine. She is co-editor of Gender, Politics and Islam (2002) and Intersections: Gender, Nation and Community in Arab Women’s Novels (2002). Her essays have appeared in Arab & Arab American Feminisms, Arabs in America, Food for Our Grandmothers, and other collections and journals. Saliba is on the advisory board of the online Brill Encyclopedia of Women and Islamic Cultures and Gaza Mental Health Foundation, and works locally with the Rachel Corrie Foundation for Peace & Justice.

Pingback: "Naming Our Destiny": Afterword to The Feminist Wire's Forum on June Jordan - The Feminist Wire

Pingback: June Jordan’s Songs of Palestine and Lebanon |