COLLEGE FEMINISMS: “Real” Women: A Critique of “Feminist” Transphobia

By Rebecca Long

As awareness of the harmful affects of the presentation of distorted female bodies in media and advertising has risen, so too has the use of phrase “real woman.” Generally employed by advertisers in campaigns like Aerie Real and Dove’s “Campaign for Real Beauty,” the term is often applied to images of women whose physical appearances are supposed to challenge stereotypical depictions of beauty. Could it be that the media, corporations targeting women’s business, and advertising agencies are finally listening to criticism? Undoubtedly, the use of this phrase is intended to acknowledge the lack of true representation of women in physical images and in film. The average model is extremely thin, tall, and generally white, women in print ad-campaigns are more often than not photoshopped in order to adhere to popular conceptions of feminine beauty, and women of color, women with disabilities, transgender women, and women with larger bodies are rarely represented at all.

True, the growing utilization of the phrase “real woman” in marketing campaigns and the pairing of such language with “real” images is an assertion that the majority of women we see in media are not in fact “real.” It also acknowledges that the mislabeling of artificial bodies as normal is a key component to constructing a false image of womanhood that is internalized by, and harmful to, women. In this way, the use of the term in advertising is an attempt at self-reflexivity, and perhaps even an apology for the decades of fake and damaging depictions of women’s bodies in media. However, the language of such a phrase is problematic and essentialist. By using the word “real,” the implication that some women qualify as legitimate and some do not is always present.

By pairing such a loaded phrase with a particular image, corporations assert that the women they depict in their advertisement are “real” while others are deviant. In this way, billboards, print ads, and online commercials that attempt to redefine womanhood and attractiveness still link beauty and normalcy with a specific representation of “woman.” In their eagerness to comply with growing criticisms of predominant images of women’s bodies, they essentialize the image of woman and overlook the very real differences among women. Moreover, companies that use such language like Aerie and Dove (which is owned by Unilever, the same company that owns Axe) are still ultimately trying to sell a product. Although they write gleaming taglines such as, “we now feature REAL women” and “this is what REAL beauty looks like,” they sell lingerie and beauty products – lotion, makeup, bleach, anti-wrinkle cream, self tanner, hair removal supplies, hair dye, soap, nail polish, deodorant, skin cleansers – and ultimately profit from women’s insecurity and the desire to fit a particular definition of women’s beauty.

Additionally, while many self identifying feminists are quick to admonish this growing marketing ploy as problematic, they at times fail to recognize the oppressive nature with which they use the same logic of “realness” to exclude trans women from so-called feminist spaces.

As suggested by Susan Stryker in Transgender History, it was a common belief among second-wave feminists, that “a feminine male-bodied person…should work for the social acceptability of sissies and be proudly effeminate instead of pretending to be a ‘normal’ woman, or a ‘real’ one” (2). This language sounds eerily similar to that used by advertisers to capitalize on women’s lack of body confidence. Both the sale of beauty products and the exclusion of trans women from feminist spaces operate on the assumption that some women are only “pretending,” and therefore unreal. REAL women buy the beauty products sold for “real women.” REAL women occupy feminist spaces; trans women do not. Just as marketing campaigns use the phrase to sell a product under the guise of inclusivity and normalcy, so too do feminists use the qualification, REAL, to justify their transphobia and transmisogyny. In both instances, the phrase is not just employed to exclude certain women, but also to devalue their experiences of womanhood.

Let me be explicit here: Trans women are not simply marginalized or excluded. Rather, their very identities are denied, and often by the very feminists who advocate for gender justice.

To illustrate this in Gender Outlaw: On men, women, and the rest of us, Kate Bornstein quotes Janice Raymond, an early proponent of trans exclusionary feminism. Raymond asserts, “ ‘Rape, although it is usually done by force, can also be accomplished by deception…in the case of the transexually constructed lesbian-feminist, often he is able to gain entrance and a dominant position in women’s spaces’ ” (in Bornstein 75).

Many, like Raymond, attempt to hide their transmisogyny by disguising it as a legitimate “feminist” concern. Trans women’s successful “penetration” of cisgender-feminist spaces is often compared with literal, forcible penetration: rape—a violent comparison that requires our feminist attentions. Above, Raymond invalidates trans women’s experiences by using male pronouns and undermines their self-identifications. Fearful of the adulteration of “women’s” spaces, Raymond intentionally misgenders and separates trans women to construct a “real,” cisgender women.

Feminist spaces often still have invisible and oppressive restrictions and caveats on their “Welcome!” signs. The transphobia originally expressed by Raymond in the 1970s remains today. For example, this summer, the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival banned trans women for not being “woman” enough. Last year, prominent radical feminist Sheila Jeffreys published Gender Hurts: A Feminist Analysis of the Politics of Transgenderism, which attempts to dispel transgender people as “disordered.”

These examples do not exist on the fringes of feminist thought. Feminism has a long history of failing women with intersecting identities. Although bastions of acceptance for those who are white, middle class, and cisgender, dominant feminisms continue to marginalize people who challenge homogeneous and binary gender categories. Women’s spaces are regularly unwelcoming and unsafe for women.

The ramifications of transphobia extend far beyond the exclusion of trans women from feminist and women’s spaces. Recently, “Injustice at Every Turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey” found that 41% of the transgender individuals they surveyed had attempted suicide, well above the 1.6% suicide rate of the general population. According to GLAAD, 53% of documented anti-LGBTQ homicides were trans women in 2012. According to the US Office for Victims of Crime, 50% of all trans individuals in the US are sexually abused or assaulted within their lives. Trans people are turned away from shelters, discriminated against in the workplace, excluded from competitive sports, and forced to “match the gender…on their government issued ID[s]” to get through airport security. In all states but California, it is legal to us a “panic defense” to justify the murder of trans and gay individuals.

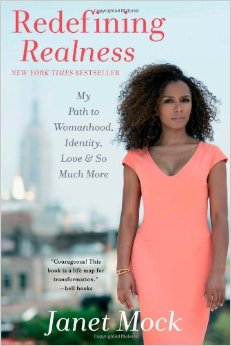

Even as the subject of transgender identities becomes less taboo and trans activists like Janet Mock and Laverne Cox gain visibility, trans people, and particularly trans women of color, experience astonishing violence.

This in mind, the feminist community must rethink what it means to be a woman and reevaluate how it advocates for gender justice. Given the brief examples above, it is clear that Raymond’s argument is not only false, but also harmful and violent. As feminists, we must assert that all who self-identify as women are “real” women and seriously challenge this construction of the “real.” As Stryker notes, “a feminism that makes room for transgender people…calls into question the usefulness of ‘woman’ as the foundation of all feminist politics” (3).

More accurately, a feminism that makes room for transgender people calls into question the usefulness of female as the foundation of all feminist politics. Too often, the constructions of female and woman are conflated. A feminism that not only includes trans women, but also approaches the world through a trans women politics cannot function on the assumption that there is a universal, biologically female “real woman” or that sex and gender necessarily fit into neat, binary categories. To afford the label of realness to only some people based on cis-status, weight, race, ability, or sexuality in advertisements and in feminist spaces is exclusionary and, as illustrated above, harmful.

How can a movement rooted in challenging patriarchal power structures and striving for the liberation of all people, dehumanize trans women and define their identities as inherently fake or deceptive? In denying trans women as “real” women, many feminists essentially say, “I do not advocate for you.”

Although feminists aim to shift the oppressive institutions that disempower ALL marginalized people, we often reproduce the very violence we are trying to eradicate. In order to intervene in feminist transphobia, we must first examine the ways in which we actively or passively retain internalized prejudices.

As a white, heterosexual, able-bodied, cisgender woman, I will never experience the oppression that a trans, queer, women of color navigates every day. I cannot speak for the trans community, but I can acknowledge my privilege and speak up. To be a feminist means to be concerned with all instances of violence, regardless of whether or not they are directed at a community I identify with. All forms of oppression are feminist concerns; a feminism that only advocates for some is not a feminism I want to be apart of. As stated by Audre Lorde, “I am not free while any woman is unfree, even if her shackles are very different from my own” (The Uses of Anger). I must be self-reflexive and attentive, listening to others’ experiences, should they wish to share them.

I believe a truly radical feminism is able to recognize that womanhood is not predicated on femaleness. Women are more than their sex organs, which do not necessarily consist of ovaries, a uterus, or a vagina. A truly radical feminism is intersectional, inclusive of difference, unafraid of internal examination, and open to change. There is no universal, “real woman.” Rather, there are women, all of whom are real.

***********************

Rebecca Long graduated in May 2014 from Allegheny College in Pennsylvania with a B.A. in English Literature and minors in Women’s Studies and History. She currently works as an Editorial Assistant at an academic publishing company in her sunny home state of California.

Rebecca Long graduated in May 2014 from Allegheny College in Pennsylvania with a B.A. in English Literature and minors in Women’s Studies and History. She currently works as an Editorial Assistant at an academic publishing company in her sunny home state of California.

Pingback: What makes a “real” woman? | socialessentialism

Pingback: Many Women, Different Shackles | thefeministblogproject

Pingback: Vegan Chews & Progressive News {3-6-15} | Chickpeas and Change

Pingback: The Sacred Image and Transwomen in Butler’s fiction | Speculative Fiction