The Weight in Being Well: The Salt Eaters and the Genius of Toni Cade Bambara

By Guest Contributor on November 19, 2014By Joel Diaz and Steven G. Fullwood

Introduction

What follows is a short excerpt from a conversation education advocate Joel Diaz, and I were having about The Salt Eaters written by my beloved Toni Cade Bambara. I’ve been in love with the Bambara, and the book since forever, and suggested it to everyone I knew. Joel, a thoughtful creative man, recently read the book and after meeting a few times to discuss it, we decided to share our impressions, theories and experiences about Salt with an audience.

We want you, reader, to read the book. And if you’ve read before to read it again. Salt is a healing text that rewards with each reading. We encourage you to delve into this amazing book and to wrestle with what the weight of being means to you, to our communities, and to our world.

—Steven G. Fullwood

********************

“Are you sure, sweetheart, that you want to be well?”

—Minnie Ransom“Not all wars have casualties, Vee. Some struggles between old and new ideas, some battles between ways of seeing have only victors. Not all dying is the physical self.”

—Sophie Heywood

Finding the Salt

Joel Diaz: Here’s how I came upon the book, Steven. You were giving a talk at a Black Arts Movement program and showcased a list of resources from the Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division related to the movement. When you mentioned The Salt Eaters, you prefaced it by saying a couple of things. You read the first line, “Are you sure, sweetheart, that you want to be well?” I remember being

intrigued by this question, but more captivating was your follow-up comment: “If you want to know what to do in the wake of George Zimmerman’s acquittal of killing Trayvon Martin, you should read this book.”

I so desperately wanted to act, to respond to the injustice that young black and brown America had endured. I needed answers, so I tapped on your shoulder and expressed my interest in reading the book. Shortly thereafter, you gave me a copy of Salt.

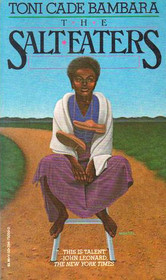

Steven G. Fullwood: Well, in reference to my comment about the Zimmerman verdict, what I was getting at was that when black people witness or  experience an injustice so profoundly perverse, so vile and painful, before acting we need sustenance, we need perspective and we need to figure out how to change shit. The Salt Eaters is the story of Velma Henry, a black woman activist who tries to commit suicide and is treated by Minnie Random, a healer. We can talk about what health and healing means as black or brown person in the U.S. today, and how Salt reminds us of the hostile racist context in which we have always existed.

experience an injustice so profoundly perverse, so vile and painful, before acting we need sustenance, we need perspective and we need to figure out how to change shit. The Salt Eaters is the story of Velma Henry, a black woman activist who tries to commit suicide and is treated by Minnie Random, a healer. We can talk about what health and healing means as black or brown person in the U.S. today, and how Salt reminds us of the hostile racist context in which we have always existed.

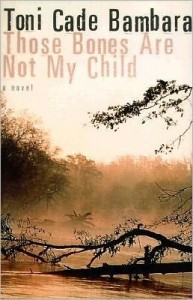

As for how the book ended up in my heart, I suspect it was because my best friend Carla had read Gorilla, My Love and raved about it, so of course I had to. I loved the stories “The Johnson Girls” and “Raymond’s Run.” Later, I found her anthology The Black Woman and a cassette tape of her reading her work (don’t know where it is now), which led me to The Salt Eaters. I wasn’t ready for it. I needed to be a better reader, thinker and lover of people, life and living  before I was able to complete the book several years later. And it paid off. Bambara loved black people, and I love her for it. Salt led me to Savoring the Salt: The Legacy of Toni Cade Bambara edited by Linda Holmes and Cheryl Wall, Conversations with Toni Cade Bambara edited by Thabiti Lewis, and most recently A Joyous Revolt: Toni Cade Bambara, Writer and Activist, Linda Holmes’s lovely new work. No other writer speaks to me in the way that Bambara does. I’m starting on These Bones Are Not My Child soon.

before I was able to complete the book several years later. And it paid off. Bambara loved black people, and I love her for it. Salt led me to Savoring the Salt: The Legacy of Toni Cade Bambara edited by Linda Holmes and Cheryl Wall, Conversations with Toni Cade Bambara edited by Thabiti Lewis, and most recently A Joyous Revolt: Toni Cade Bambara, Writer and Activist, Linda Holmes’s lovely new work. No other writer speaks to me in the way that Bambara does. I’m starting on These Bones Are Not My Child soon.

Joel Diaz: “Are you sure sweetheart that you want to be well?” I marinated on that first line for hours. It echoed in my spirit. It was haunting and courageous question. Haunted in the sense that I knew my inner fears and insecurities were going to be questioned and interrogated. I understood that this book would refuse me the space to be disillusioned and that it was going to hold a mirror up to my face. My patterns, unhealthy responses, and truth were going to be illuminated. I often say that you can teach an entire semester by only reading the first 20 pages of the book, because it’s so dense and rich. The Salt Eaters elucidates a catalyst for change. It became my bible of healing. The book made me question healing in holistic way.

Interpreting Salt

Wasn’t that what happened to Lot’s Wife? A loyalty to old things, a fear of the new, a fear to change, to look ahead?

I must admit, it was difficult to read Salt for many different reasons. Aside from the emotionally interrogative first line, I became fixed on exploring the symbolism of salt. What the hell was salt? Why were people eating it? Why did she title the book, The Salt Eaters? I spent a lot of energy trying to find answers, and what I found was that salt represents the edge, the chip on your shoulder, the anger carried inside burning the flesh. But also, salt as necessity. You need a bit of saltiness to act, to feel something, to feel alive. Readers discover, however, that too much salt can be debilitating and can ossify you in brokenness, and keep you self-destructive.

…the difference between eating salt as an antidote to snakebite and turning into salt, succumbing to the serpent.

I entered the book on a zealous mission to love myself. I was, and still am, on a journey of growth and healing. Of love and understanding. Of learning to forgive. I lived for the Toni-isms. The “there is a lot of weight to being well” and “being well is no trifflin’ matter” quotes. I feverishly searched for more, wanting to be humbled, stopped in my tracks, to evolve. But I was frustrated by her style of writing and that she was constantly going off on tangents.

Steven: Her style, at least in Salt I think, is improvisational. Tangents aren’t really tangents in the sense that they have nothing to do with the main story. Instead they add flavor and robustness and texture to her narrative. Salt demands one treat the whole self rather than parts.

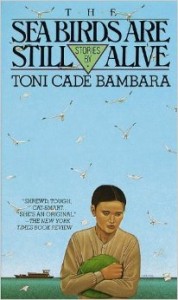

Joel: I realized that Bambara occupies the center of the book. The center as a place of focus, a place to realign, a nucleus of the self, where one can continuously retreat to when the outside world has drawn folks away from being grounded and toward insanity. The center is a place to position yourself, an ideal location to observe all that is manifesting and happening around you. Bambara, as the writer, positions herself in the center, and here is where the main narrative exists. In Salt, Velma’s life is the central narrative. We are taken to the outskirts of the circle, to explore here experiences and the lives of those surrounding her. Bambara, however, always returns to the center, to realign and remind us as the readers what the stakes are in seeking to be whole and then back again to the lives of the supporting characters.  These are the tangents I so frustratingly sought to understand. The same technique can be seen in her other works, These Bones are Not My Child and The Sea Birds Are Still Alive.

These are the tangents I so frustratingly sought to understand. The same technique can be seen in her other works, These Bones are Not My Child and The Sea Birds Are Still Alive.

Steven: What you’ve identified as a way into reading Salt is remarkable. Two things came to mind when you were talking. Toni Morrison once said of Bambara is that she writes black. To me, she meant black people, black bodies, black language, black culture, black history, black here, black there, black every damn where. African-derived. Ancestral. This centering is one of the hallmarks of her Bambara’s work meaning that she gives black people the space to be center, not slip into stereotype or be used as a point of reference or magical Negroes by innocent white people. Bambara lets us talk, Bambara lets us be.

Her characters’ inner lives mean a great deal to me. As I’ve said, I tried reading Salt several times. The book helped me read it. That is, Salt requires a close, but flexible, reading. I started listening closely to the way some black people spoke: the cadences they utilized and the way that they rolled their “Rs,” and how they spoke to one another heavy with gesture. Mmmph and a roll of the eyes, and you know exactly what that person thinks. Bambara’s language is also gorgeous and packs a serious punch.

The gathering of fresh things, natural things, fish herbs, salad greens. Natural growth, no forced foods to weaken the will to live. No old, dead food for the folks of her boardinghouse. Food in tin cans on shelves for months and months and aged meat developing in people’s system an affinity for killed and old and dead things.

I’m very aware of nature and circularity when it comes to reading Bambara’s work. Everything is commenting on how we see and experience the world in Salt. You have Velma, and surrounding her with healing energy is Minnie, who is also in conversation with her spirit guide. Encircling Velma, Minnie and her spirit guide is the Master’s Mind, and they are surrounded by Western medicine residents who all are surrounded by the forests, animals, insects, etc. And there are levels of circularity. Each person is wrapped in their own thing, mired in memory, impaled on impressions of the world, time forever fleeting, time forever traveling. Bambara doesn’t meet the conceits of the ways in which we were taught to read literature and how wonderful is that?

Joel: It’s genius. What I said earlier is filtered through a literary perspective, the patterns and style of her writing. I also read the book using a therapeutic lens. I found myself in the experiences of the characters. When people endure traumatic and exacerbating conditions, the body retreats to feel safe, and in turn develops its own defense mechanisms.

Joel: It’s genius. What I said earlier is filtered through a literary perspective, the patterns and style of her writing. I also read the book using a therapeutic lens. I found myself in the experiences of the characters. When people endure traumatic and exacerbating conditions, the body retreats to feel safe, and in turn develops its own defense mechanisms.

Steven: One of my favorite characters, Fred Holt, the bus driver, who misses his good friend Porter, talks to him in his head and feels the sting of his absence.

…Fred Holt was brimming over with rage and pain and sadness…Porter. So neat, so well read, so unfull of shit. One of the few guys around who could talk about something other than pussy, poker, pool and TV. Had wanted to be a newspaper reporter, go all over the world, go to Africa, piercing together what they knew and trusted to counter the hooey handed to them in newsmagazines.

Joel: I think Bambara captured this passage beautifully. One is often not conscious during the process of dissociation. One leaves the room, transported into a memory where past experiences become vivid and replay themselves can breed stoicism. She identifies this process within Velma, and describes it as a “telepathic visit with her former self.”

The underlying theme, guiding principle and the inherent lesson in Salt, in my opinion, is wellness. How do we initialize agency over our health, and accept the responsibility to maintain it? Answers are present in the relationship between characters. They have an incessant need to love, care and support others while simultaneously rejecting that kindness for themselves. Obie, Velma’s husband, verbally expresses his desire for Velma to be emotionally courageous, to release all the pain and forgive. However, Obie has not figured out how to do this in his own life. Readers witness Obie’s own struggle in his conversation with Ahiro, a masseuse who urges Obie to release, to rid himself of the excess salt in his body:

A good cry, man. Good for the eyes, the sinuses, the heart. The body needs to throw of its excess salt for balance. Too little salt and wounds can’t heal. Remember Napoleon’s army? Those frogs were dropping dead from scratches because their bodies were deprived of salt. But too much—

—Ahiro

I wasn’t taught courage. Toni Cade Bambara gave me the advice I wished my mother would have given me. For Bambara, courage is at the crux of wholeness. Sometimes we are so comfortable in our pain that it immobilizes our ability to imagine possibilities. To be courageous, one must be willing to stand in vulnerability, to stand firm in the uncomfortable truth. This is precisely the reason why Minnie Ransom, the healer, reminds us that “being well is no trifling matter.” She flatly states that “there’s a lot of weight when you’re well.” She emphasized that healing is an ongoing thing and requires perpetual effort. As a people in need of healing, who so desperately want to be happy, we underestimate the profound commitment to be healthy.

I wasn’t taught courage. Toni Cade Bambara gave me the advice I wished my mother would have given me. For Bambara, courage is at the crux of wholeness. Sometimes we are so comfortable in our pain that it immobilizes our ability to imagine possibilities. To be courageous, one must be willing to stand in vulnerability, to stand firm in the uncomfortable truth. This is precisely the reason why Minnie Ransom, the healer, reminds us that “being well is no trifling matter.” She flatly states that “there’s a lot of weight when you’re well.” She emphasized that healing is an ongoing thing and requires perpetual effort. As a people in need of healing, who so desperately want to be happy, we underestimate the profound commitment to be healthy.

I think that readers need to be brave before beginning the book. I truly believe that you will only be able to receive the book if you are ready to read what’s inside. Wounds will be pried open. Be prepared to be transformed.

The Weight in Being Well

‘I am one beautiful and powerful son of a bitch,’ he told himself. ‘Smart as a whip, respected, prosperous, beloved and valuable. I have the right to be healthy, happy and rich, for I am the baddest player in this arena or any other. I love myself more than I love money and pretty women and fine clothes. I love myself more than I love neat gardens and healthy babies and a good gospel choir. I love myself as I love The Law. I love myself in error and in correctness, waking or sleeping, sneezing, tipsy, or fabulously brilliant I love myself doing the books or sitting down to a good game of poker. I love myself making love expertly, or tenderly and shyly, or clumsily and inept. I love myself as I love The Master’s Mind,’ he continued his litany, having long ago stumbled upon the prime principle as a player–that self-love produces the gods and the gods are genius. It took genius to run the Southwest Community Infirmary. So he made the rounds of his hospital the way he used to make the rounds of his houses to keep the tops spinning, reciting declarations of self-love.”

—Doc Serge

Steven: There’s weight in being well? Shit, could it be any more difficult in being ill? I knew illness,

intimately, believing that health was reserved for the born lucky (white people) or the compliant (good citizens, not rabble-rousers). Still, knocking up against that thought was another persistent and insistent one: health is everyone’s right, Steven, and you have to surround yourself with good people with good energy, get to the good stuff you thought was outside you, because you had been lied to all these years about your value in and outside of the embattled community that gave birth to you.

So I feel you, Joel: How do you learn how to heal? As Salt demonstrates, it can’t be done solely through speaking. There needs to be music, laughter, tears, and probably lots of sex, food and sleeping. Perhaps a shout or whistle to align the spine to recharge one’s Kundalini. I can only imagine that there are endless ways to move into better health than what we currently imagine waiting to be recognized and utilized. But there is a terror of nuance in the US despite our obvious complexities. A terror of being seen through someone’s eyes as not enough, ever, I suppose. It blocks our ability to stand naked in our unique and beautiful truths.

And I agree, Salt is a book about healing from many perspectives. Those obviously broken (Velma), those in the know and are trying (Minnie, and her spirit guide, Obie, Doc Serge), those who don’t know they need to heal (Fred Holt), those on a journey to health and healing (The Seven Sisters), and those invested in curative medicine (the residents from the local hospital.) The most challenging call from Bambara is to truly understand what it means to be well and our responsibility to remain well in the midst of this ongoing systemic campaign of dehumanization targeting black and brown people. As a tonic, Doc Serge’s litany of self-love while making rounds at the Southwest Community Infirmary might be one of the best things I’ve ever read. His self-declarations of love feel right on target. Perhaps daily or even hourly reminders to us about our value are a very good start.

Joel: I’d like to add that people and energies are perpetually attacking our spirits. Velma, a woman, an activist, a mother, a wife, refuses to sit on the sidelines. She refuses to do all the work, while men take all the credit. We watch her go to lengths to ensure she is not diminished or devalued. That act, in of itself, is revolutionary. The path toward righteousness, toward liberation, comes with significant challenges.

Joel Diaz is currently an Education Associate at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Diaz received his M.A. in Educational Leadership from New York University and a B.A. in American Studies from Wheelock College. His research interests include juvenile justice and youth advocacy, positive youth development, and challenging heteronormative practices in educational settings.

Joel Diaz is currently an Education Associate at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Diaz received his M.A. in Educational Leadership from New York University and a B.A. in American Studies from Wheelock College. His research interests include juvenile justice and youth advocacy, positive youth development, and challenging heteronormative practices in educational settings.

Steven G. Fullwood’s recent publication Black Gay Genius: Answering Joseph Beam’s Call (co-edited with Charles Stephens) is a community’s response to the love and legacy of activist Joseph Beam. Fullwood is also co-editor of other anthologies, Think Again and To Be Left with the Body, and the author of Funny. His articles, essays, poems and criticism have appeared in Black Issues Book Review, Lambda Book Report, Vibe, Library Journal, and other publications. Fullwood currently serves as the head of the Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library, and is the founder of the In the Life Archive, a project to acquire, preserve and make available to the public materials created by and about LGBTQ people of African descent.

You may also like...

4 Comments

All Content ©2016 The Feminist Wire All Rights Reserved

Pingback: Afterword: Toni Cade Bambara's Living Legacy - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire