Toni Cade Bambara: ‘…an uptown Griot’

By Guest Contributor on November 28, 2014By Cheryl Clarke

Editors’ Note: Since this is a special forum celebrating the life, work, and legacy of Toni Cade Bambara, one of our ancestor heroines, TFW made the editorial decision to republish Cheryl Clarke’s “Toni Cade Bambara: ‘…an uptown Griot,’” as Clarke was a peer and contemporary of the celebrant. This piece was originally published during a one-day mini-forum on March 25, 2014, which would have been Toni Cade Bambara’s 75th birthday.

In March 2005, Cheryl Clarke was the featured keynote speaker at Spelman College’s Women’s Research and Resource Center’s Toni Cade Bambara Scholar-Activism Conference. The Feminist Wire (TFW) is elated to offer here the 2014 edited version of her previously unpublished talk on the occasion of Bambara’s 75th birthday anniversary.

Toni Cade Bambara: “…an uptown Griot [who] learned from the street’s memory the corniness of atavism…”

—Amiri Baraka, Eulogies (1996)

Toni . . . . converted the concrete dialectic of our struggle into a complex reflection of people’s lives and minds.

—Amiri Baraka, Eulogies (1996)I knew a girl who ‘desegregated’ the local white high school in her small town.No one, except her teachers, spoke to her for four years. . . .

Even her parents talked only about the bravery, never about the cost.

—Alice Walker, “Looking to the Side, and Back,” In Search of Our Mother’s Gardens (1979)Are you sure, sweetheart, you want to be well?

—Toni Cade Bambara, The Salt Eaters (1980)

Fortunately, Toni Cade Bambara’s words (and prose) were only enhanced by knowing her. She was always respecting bald-faced honesty and people’s hidden agendas, always asking the cost, and always wanting to know if you had the stamina for health, i.e. change. She was always reaching out, touching you, cracking you up, making you reach, be the best self you could be, and if you couldn’t be that best self, she was ever patient, but went on about her business—which was always liberation, all over the world. She charged us to: “Make revolution irresistible.” Toni Cade was “irresistible” as far as I was and am concerned…I don’t want to be “corny” as Baraka said Toni never was. So, how far back do I want to go with my memories of Toni Cade Bambara?

Mostly we saw one another in transit at Port Authority in Manhattan: she’d be on her way to the subway back to Manhattan, uptown to where she lived on Riverside Drive, I’d be on my way to get the bus back to New Brunswick, N.J., where I lived during the 1970s and 80s.

The Black Woman: An Anthology from 1970, which Toni edited…is still one of the books I live by. Really, until Barbara Smith and Lorraine Bethel edited Conditions: Five, the Black Women’s Issue in 1979, The Black Woman and Gerda Lerner‘s Black Women in White America were really the only two works that addressed black women’s expressivity and history in relation to feminism. So, Toni Cade Bambara is still influencing black women’s consciousness of ourselves every day since then. She, like Audre Lorde, is such a good neighbor.

Then there was her stunning “Foreword” in Cherríe Moraga‘s and the late Gloria Anzaldua‘s 1981 This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, which is where she charged the new generation of feminists of color—and I was one of them—to “make revolution irresistible.” This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color is still a book I live by, because of Toni, not that I don’t live by Cherríe’s and Gloria’s work.

Then there was her stunning “Foreword” in Cherríe Moraga‘s and the late Gloria Anzaldua‘s 1981 This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, which is where she charged the new generation of feminists of color—and I was one of them—to “make revolution irresistible.” This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color is still a book I live by, because of Toni, not that I don’t live by Cherríe’s and Gloria’s work.

As early as 1969, before the second wave of black feminism really took hold, Toni Cade said the following at the “Black Woman’s Seminar” at Livingston College[Rutgers University, where she taught for almost five years. The talk was entitled, “On the Issue of Roles” and later published under the same title in The Black Woman: An Anthology edited by Bambara in 1970, where I first read it:

Perhaps we need to let go of all notions of manhood and femininity and concentrate on Blackhood. We have much, alas, to work against. The job of purging is staggering. It perhaps takes than to face the task of creating a new identity, a self, perhaps an androgynous self, via commitment to struggle.

Taken out of context, it may seem prophetic in light of the post-modern thinking that urges us to retreat from either/or thinking, but given the black nationalist context out of which she was writing and extolling, it was still an act of courage, for the boundaries of blackness and gender conformity were sharply policed. Given all that, the statement has always, always intrigued me…I think we should dwell on it. I think we might consider how it might motivate us to act now and in the future, in the name of women like Toni Cade Bambara. How do we consider the words of black women—[as writers, as activists, as intellectuals, as scholars, as workers]?

Perhaps we need to let go of all notions of manhood and femininity and concentrate on Blackhood.

The heavy black nationalist trend that dominated both the political and artistic facets of the black liberation movement splintered over sex roles predicated on male dominance, compensatory male dominance at that. Should you ask yourselves, as the next generation of people who are going to change the world, what will it mean to “let go” of our notions of gender, “‘manhood and femininity,'” which are rather an asymmetrical pairing. Interesting that Bambara says “manhood” instead of “masculinity” and “femininity” instead of “womanhood.” The usages demonstrate what fraught topics among black people are our performances of the material and social constraints of sex and gender, of being men and being women, and of being masculine and being feminine. At any rate, to consider this possibility, I might have to give up some of what it has meant to me for the past 31 years to be a lesbian, to be a feminist, to be a black woman writer. What would that be generative of: perhaps a more democratic method/model of leadership development, based on talent not on sex or gender [or gender expression] or sexual orientation. African-American revolutionaries were still foundering on the rock of sexism in 1969 even as they sought enlightenment on the so-called “woman’s role” in the revolution. And Toni was rarely less than revolutionary.

The heavy black nationalist trend that dominated both the political and artistic facets of the black liberation movement splintered over sex roles predicated on male dominance, compensatory male dominance at that. Should you ask yourselves, as the next generation of people who are going to change the world, what will it mean to “let go” of our notions of gender, “‘manhood and femininity,'” which are rather an asymmetrical pairing. Interesting that Bambara says “manhood” instead of “masculinity” and “femininity” instead of “womanhood.” The usages demonstrate what fraught topics among black people are our performances of the material and social constraints of sex and gender, of being men and being women, and of being masculine and being feminine. At any rate, to consider this possibility, I might have to give up some of what it has meant to me for the past 31 years to be a lesbian, to be a feminist, to be a black woman writer. What would that be generative of: perhaps a more democratic method/model of leadership development, based on talent not on sex or gender [or gender expression] or sexual orientation. African-American revolutionaries were still foundering on the rock of sexism in 1969 even as they sought enlightenment on the so-called “woman’s role” in the revolution. And Toni was rarely less than revolutionary.

The prose in [“On the Issue of Roles”] proceeds along at the usual Bambara clip, with a deadpan, tongue in cheek, death defying critique of the West and the “dangerous trend observable in some quarters of the Movement to program Sapphire out of her ‘evil’ ways into a cover-up, shut-up, lay-back-and-be-cool obedience role,” of professing to be about liberation but behaving in a “constricting manner.” Performing a Marxist perspective, Bambara casts a paradigm of man as commodity fetishist and woman as commodity fetishizer—which is why she, Toni, is a revolutionary, because she wants to change the whole person, which is antithetical to the either/or of “masculine and feminine,” which maintains “dudes” as the producer of power, i.e., the subjects; and “chicks” as the consumers of power, i.e., the objects. But she was asking us to put the correct racial politics before correct sexual politics, in order, to stop fetishizing whiteness, Christianity, and the nuclear family.

Bambara grants far too much agency to white people and far too much virtue and victimhood to the pre-capitalist and non-white, indigenous, aboriginal cultures of the world, where everything was communal and inclusive, with no squabbling over “yours” and “mine”—a product of its black nationalist times. She places the blame on “whiteness” for all our problems as a community, as a movement, and reifies the black man and woman as the “couple” accountable for protecting and holding together the “family, the cell, the movement”—asks us, way back there in the time and place of black nationalism:

to submerge all breezy definitions of manhood/womanhood (or reject them out of hand if you’re not squeamish about being called ‘neuter’) until realistic definitions emerge through a commitment to Blackhood.

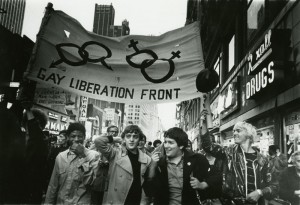

As you can see, being policed was a real experience, borne out by the parenthetical advice “if you’re not squeamish about being called ‘neuter'” (109). What does “neuter” mean here and why should one “fear” being called neuter? Is it some kind of code word for homosexual? And why does she use the epithet, “faggot,” I think uncritically twice in this piece [even though “faggot” had just been reclaimed by the gay liberation movement, which could explain her use of it. She did live in New York City, the home of Stonewall]. However, homosexuality, particularly male homosexuality, I think, is the white elephant in the room her in 1969—and still is if you will pardon the pun/paradox of a “white elephant.” And so, implying uncritically that to defy black manhood by being gentle is to be a “faggot” and imputing a type of sexlessness—i.e., “neuter”—to one who might resist gender proscription are the prices Toni Cade paid for being able to critique sex role prescription and male chauvinist black nationalism in 1969 at Livingston College [Rutgers University], where blackness was heavily policed.

As you can see, being policed was a real experience, borne out by the parenthetical advice “if you’re not squeamish about being called ‘neuter'” (109). What does “neuter” mean here and why should one “fear” being called neuter? Is it some kind of code word for homosexual? And why does she use the epithet, “faggot,” I think uncritically twice in this piece [even though “faggot” had just been reclaimed by the gay liberation movement, which could explain her use of it. She did live in New York City, the home of Stonewall]. However, homosexuality, particularly male homosexuality, I think, is the white elephant in the room her in 1969—and still is if you will pardon the pun/paradox of a “white elephant.” And so, implying uncritically that to defy black manhood by being gentle is to be a “faggot” and imputing a type of sexlessness—i.e., “neuter”—to one who might resist gender proscription are the prices Toni Cade paid for being able to critique sex role prescription and male chauvinist black nationalism in 1969 at Livingston College [Rutgers University], where blackness was heavily policed.

Is she asking us to cling to a kind of hierarchy of oppressions and solve all our racial ills before we solve our sex role ills; or is she asking us to just suck it up and transcend all the sex role division, which would create some kind of synthetic blackness that might enable us to revolutionize the self. She reproduces some of the dichotomizing she is working against by uncritically elevating the male-female paradigm as the ideal unit, from which the revolution proceeds after the self, and dissolves into an indictment of revolutionaries (male) tending to the business of the world while their own communities and families are being neglected.

We have much, alas, to work against. The job of purging is staggering.

But even Toni Cade Bambara got tired of the staggering job of purging.

It perhaps takes less heart to pick up the gun than to face the task of creating a new identity, a self, perhaps an androgynous self, via commitment to struggle.

As the struggle is revolutionary, ever moving, ever changing, our commitment should not be tied to the corrosive paradigms of male “functions” and female “graces”—and will not necessarily be generative of a new self. [This new self] seemingly transcends and transmutes these heretofore immutable identities—male and female, man and woman, masculine and feminine. Anyway, Toni Cade Bambara was correct about the staggering struggle that still must be waged against the old self/selves. This “new self” will not emerge pure and uncontaminated, even for those of us who organize across differences of race, gender, sexual lines and who are fighting—like Toni did—for a world where social justice prevails [not this world we live in]. Thus, she seems to imply that because we can’t seem to transform ourselves, we are doomed to either/or choices like that choice between “picking up the gun” or “creating a new identity, a self, perhaps an androgynous self, via commitment to struggle.” “Androgynous” is standing in for the refusal to accede to an either/or option and to have one’s talents stunted because one refuses to be a traditional man or a traditional woman…

Between 1988 and 1993, I enjoyed two of the greatest privileges of my life when I spent time with Toni Cade Bambara: in 1988, I was sharing the black history month bill with Toni and Rita Dove at a small Southern women’s college in Virginia called Sweetbriar. And in 1995, [my student affairs department] was co-sponsoring a women’s history month program with the Women’s Studies Program [not a department yet] at Rutgers, and Toni was our speaker/artist for that month. And sadly, 1995 was the last time I was to see her. Both experiences are so vibrant still [even in 2014]. I return to them over and over in my heart and mind, and they continue to be a balm for the ache produced by losing someone like Toni Cade Bambara. [She], like Audre Lorde, is one of a sorority of black women writers whose work and lives changed the world. They were both out there, in the world. They touched so many lives…

Between 1988 and 1993, I enjoyed two of the greatest privileges of my life when I spent time with Toni Cade Bambara: in 1988, I was sharing the black history month bill with Toni and Rita Dove at a small Southern women’s college in Virginia called Sweetbriar. And in 1995, [my student affairs department] was co-sponsoring a women’s history month program with the Women’s Studies Program [not a department yet] at Rutgers, and Toni was our speaker/artist for that month. And sadly, 1995 was the last time I was to see her. Both experiences are so vibrant still [even in 2014]. I return to them over and over in my heart and mind, and they continue to be a balm for the ache produced by losing someone like Toni Cade Bambara. [She], like Audre Lorde, is one of a sorority of black women writers whose work and lives changed the world. They were both out there, in the world. They touched so many lives…

1988: By the time Rita Dove, the black history month program coordinator Bernice Grant, and I reached Sweetbriar College, a women’s institution tucked away in the mountains of Virginia, it was 9 p.m. and Toni Cade Bambara had just read from her work in progress about the more than 40 African-American children who were murdered in Atlanta in the early 80s. [Toni Morrison published Bambara’s Those Bones Are Not My Child posthumously in 2000].

1988: By the time Rita Dove, the black history month program coordinator Bernice Grant, and I reached Sweetbriar College, a women’s institution tucked away in the mountains of Virginia, it was 9 p.m. and Toni Cade Bambara had just read from her work in progress about the more than 40 African-American children who were murdered in Atlanta in the early 80s. [Toni Morrison published Bambara’s Those Bones Are Not My Child posthumously in 2000].

Bernice and I had been taking turns driving since 1 p.m. and had picked up Rita Dove at Philadelphia Community College as part of our leg down from Jersey City to Sweetbriar. Toni, Rita, and I were guests at Sweetbriar’s Black History Month celebration—I believe its first. We were to speak to the program’s theme: “Why Is There Black American Literature?'” The program sponsors welcomed Rita and myself to share the stage with Toni and be introduced to the audience, which seemed to be furiously clapping for us. Memory is not clear here, but I remember Toni really greeting Rita warmly shaking her hand or hugging—can’t remember—and congratulating her on having won her Pulitzer Prize a year or so before. She greeted me as if nearly 15 years had not elapsed, hugging me and saying, ‘Cheryl Clarke.’ Always making you feel ‘more significant.’ And that weekend, the three of us stayed up into the small hours of the morning talking to and spending time with the ten or 15 African-American young women students attending Sweetbriar. For the next two mornings, I had the most exquisite pleasure of being with two gracious, charismatic, and real sisters, Toni Cade Bambara and Rita Dove. And Toni Cade is one of the funniest people in the world. Our Saturday panel, devoted to the question “Why is there Black American Literature?” was not only attended by the Sweetbriar community but also by the off-campus community, which included members of the black middle class community. The bookstore had ordered our books, but only ten of mine while they’d ordered 25 of Rita’s and Toni’s books. I was mystified by this at first, but then later I realized it was blatant homophobia, they did not want to order any book with the title, Living As A Lesbian. Anyway, the three of us had assembled for the panel and the question, “Why is there Black American Literature?” was put to us, in alphabetical order. Toni was first. She answered acerbically, with brevity, and depth:

Bernice and I had been taking turns driving since 1 p.m. and had picked up Rita Dove at Philadelphia Community College as part of our leg down from Jersey City to Sweetbriar. Toni, Rita, and I were guests at Sweetbriar’s Black History Month celebration—I believe its first. We were to speak to the program’s theme: “Why Is There Black American Literature?'” The program sponsors welcomed Rita and myself to share the stage with Toni and be introduced to the audience, which seemed to be furiously clapping for us. Memory is not clear here, but I remember Toni really greeting Rita warmly shaking her hand or hugging—can’t remember—and congratulating her on having won her Pulitzer Prize a year or so before. She greeted me as if nearly 15 years had not elapsed, hugging me and saying, ‘Cheryl Clarke.’ Always making you feel ‘more significant.’ And that weekend, the three of us stayed up into the small hours of the morning talking to and spending time with the ten or 15 African-American young women students attending Sweetbriar. For the next two mornings, I had the most exquisite pleasure of being with two gracious, charismatic, and real sisters, Toni Cade Bambara and Rita Dove. And Toni Cade is one of the funniest people in the world. Our Saturday panel, devoted to the question “Why is there Black American Literature?” was not only attended by the Sweetbriar community but also by the off-campus community, which included members of the black middle class community. The bookstore had ordered our books, but only ten of mine while they’d ordered 25 of Rita’s and Toni’s books. I was mystified by this at first, but then later I realized it was blatant homophobia, they did not want to order any book with the title, Living As A Lesbian. Anyway, the three of us had assembled for the panel and the question, “Why is there Black American Literature?” was put to us, in alphabetical order. Toni was first. She answered acerbically, with brevity, and depth:

Because without [B]lack American literature, there would be no American literature. Black people have given American literature two enduring metaphors: doubleness and invisibility.

I don’t even remember how Rita or I answered that question, besides questioning why it was still being asked. But I will never forget what Toni said. She signed my copy of The Salt Eaters, and asked me to sign a copy of my first book of poems, Narratives: Poems in the Tradition of Black Women for her daughter, Karma, whom I had last seen as an infant in Toni’s arms at a John Henrik Clarke lecture in 1970. We exchanged addresses. We would not see each other for six or seven years.

I don’t even remember how Rita or I answered that question, besides questioning why it was still being asked. But I will never forget what Toni said. She signed my copy of The Salt Eaters, and asked me to sign a copy of my first book of poems, Narratives: Poems in the Tradition of Black Women for her daughter, Karma, whom I had last seen as an infant in Toni’s arms at a John Henrik Clarke lecture in 1970. We exchanged addresses. We would not see each other for six or seven years.

1993: I am calling a number for Toni I’d been given by her six years before then at Sweetbriar College, thinking this could surely not still be her number, as much as she moves around. A laughing voice I dare to recognize answers, ‘Hello.’ Breathless, I ask, ‘May I speak to Toni Cade?’—daring to use the old surname name by which I first came to know her in 1970. ‘This is Toni Cade.’ I nearly burst with relief that my use of only ‘Cade’ was acceptable and continued to hope she’d be open to my request that she do a mini-residency at my university. ‘Toni, this Cheryl Clarke.’ ‘Cheryl Clarke the poet.’ (Like Baraka said, ‘Toni Cade Bambara…would make us feel more significant in the world.’)

By 1988, she’d published two books of short stories, the intense award-winning novel The Salt Eaters and numerous articles. Additionally, she was completing her second novel, while simultaneously working with filmmaker Louis Massiah on The Bombing of Osage Avenue and W.E.B Du Bois documentaries. If that wasn’t enough, she was also turning out grassroots media activists at Scribe Video Center in Philadelphia. And yet, she made me feel good about myself. After a brief but friendly chat, Toni agreed to visit my school and engage us for two days. She really didn’t want to spend the night in New Brunswick. She wanted to go back in the same day so that she could work with her senior citizens group whom she was training to do film. I said, “Toni, Toni, come on, you can stay over in New Jersey for one night.” She did, and we were graced with her company for about 18 hours, during which time she gave a no-nonsense lecture, met with students for lunch, met with faculty for breakfast, and returned to Philadelphia by train that afternoon. The parting image is Toni boarding the train to Trenton, greeting the conductor and giving me a two-fingered goodbye wave.

I’ll close with a passage from Audre Lorde’s 1971 poem, “Dear Toni,” published in Lorde’s 1973 volume of poetry, From A Land Where Other People Live:

I see your square delicate jawbone

the mark of a Taurus (or Leo) as well as the ease

with which you deal with your pretensions.

I dig your going and becoming

the lessons you teach your daughter

our history. . . . I have known you over and over again

as I’ve lived throughout this city

taking it in storm and morning strolls

through Astor Place and under the Canal Street Bridge

The Washington Arch like a stone raised to despair

and Riverside Drive too close to the dangerous predawn

waters and 129th Street between Lenox and Seventh

burning my blood . . .In my daughter’s name

I bless your child with the mother she has . . . .

Our girls will grow into their own

Black Women

finding their own contradictions

that they will come to love

as I love you.

Who could help but love Toni Cade Bambara.

Cheryl Clarke is the author of four books of poetry, Narratives: poems in the tradition of black women (1982), Living as a Lesbian (1986), Humid Pitch (1989), Experimental Love (1993), the critical study, After Mecca: Women Poets and the Black Arts Movement (Rutgers Press, 2005), and The Days of Good Looks: Prose and Poetry 1980-2005 (Carroll and Graf, 2006). She continues to write poetry and essays. She has written a chapbook, entitled “By My Precise Haircut.” Though she has written many essays over the years relevant to the black queer community, “Lesbianism: an act of resistance,” which first appeared in the iconic This Bridge Called My Back: Writings By Radical Women of Color (Anzaldua and Moraga, eds., 1982) and “The Failure to Transform: Homophobia in the Black Community,” which was published in the equally iconic Home Girls: A Black Feminist Anthology (Smith, ed., 1984) continue to be favorites. She considers herself a scholar of Audre Lorde and continues to write about the impact of Lorde’s work. She recently wrote an introduction to G.R.I.T.S.: An Anthology of Writing by Southern Black Lesbians (Williams, ed., Media Arts Project, 2013). Her article, “By Its Absence: Literature and Social Justice Consciousness” will appear in The Handbook of Social Justice (Reisch, ed., Routledge, 2014). She received the Kessler Award from the Center for Lesbian and Gay Studies at the CUNY Graduate Center in 2013. She finally retired from Rutgers University in July of 2013 after 41 years of studying, teaching, and administration on the New Brunswick campus. She is co-owner with her partner of 22 years, Barbara Balliet, of Blenheim Hill Books in Hobart, the Book Village of the Catskills.

Cheryl Clarke is the author of four books of poetry, Narratives: poems in the tradition of black women (1982), Living as a Lesbian (1986), Humid Pitch (1989), Experimental Love (1993), the critical study, After Mecca: Women Poets and the Black Arts Movement (Rutgers Press, 2005), and The Days of Good Looks: Prose and Poetry 1980-2005 (Carroll and Graf, 2006). She continues to write poetry and essays. She has written a chapbook, entitled “By My Precise Haircut.” Though she has written many essays over the years relevant to the black queer community, “Lesbianism: an act of resistance,” which first appeared in the iconic This Bridge Called My Back: Writings By Radical Women of Color (Anzaldua and Moraga, eds., 1982) and “The Failure to Transform: Homophobia in the Black Community,” which was published in the equally iconic Home Girls: A Black Feminist Anthology (Smith, ed., 1984) continue to be favorites. She considers herself a scholar of Audre Lorde and continues to write about the impact of Lorde’s work. She recently wrote an introduction to G.R.I.T.S.: An Anthology of Writing by Southern Black Lesbians (Williams, ed., Media Arts Project, 2013). Her article, “By Its Absence: Literature and Social Justice Consciousness” will appear in The Handbook of Social Justice (Reisch, ed., Routledge, 2014). She received the Kessler Award from the Center for Lesbian and Gay Studies at the CUNY Graduate Center in 2013. She finally retired from Rutgers University in July of 2013 after 41 years of studying, teaching, and administration on the New Brunswick campus. She is co-owner with her partner of 22 years, Barbara Balliet, of Blenheim Hill Books in Hobart, the Book Village of the Catskills.

You may also like...

1 Comment

All Content ©2016 The Feminist Wire All Rights Reserved

Pingback: Afterword: Toni Cade Bambara's Living Legacy - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire