Toni Cade Bambara’s Art of Bridging Praxis and Theory

By Guest Contributor on November 20, 2014By Thabiti Lewis

The March 2014 issue of Ebony Magazine published an article by Jamilah Lemieux entitled “Black Feminism Goes Viral.” Lemieux mentions Black feminist figures present and past from Melissa Harris Perry, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, and Joan Morgan, to Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, Angela Y. Davis, Audre Lorde, bell hooks, Alice Walker, Maria Stewart, and Anna Julia Cooper.

One purpose of the article is to inform readers that black women remain subject to both sexism and racism (and that’s without mentioning class discrimination, homophobia, and any other number of ways in which a Black woman can be “othered” by society), yet are largely marginalized by white women and black men when those issues are being addressed. Another goal of the article is to focus on the increased representation of black feminism in pop culture and how social media has enabled young women to connect with thought leaders around gender instead of key figures. The inclusion of Beyoncé and W.E.B. Dubois and the omission of Toni Cade Bambara amongst important theorists and thought leaders was noticeable.

I loved that the article drew attention to contemporary feminism, its spread in popular culture and praise of Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s powerful TED talk “Why We Should All Be Feminists.” But I was disquieted that a full-length feature story about feminism omitted Bambara’s The Black Woman (1970) as seminal to many of the ideas finding traction in the popular sphere (the Ebony.com version of the article briefly mentions Bambara). When I think about Gorilla, My Love, which includes Bambara’s short story “Raymond’s Run,” whereby the protagonist reconnoiters very similar assertions as Adichie regarding female unity, resistance to patriarchy and gender inequity, I am left feeling uncomfortable. The “blueprint” of sorts offered by contemporary feminist like Kimberlé that: “The way to handle the crisis facing Black women and girls is first, fix what’s happening to men,” reminds me of Bambara’s astute essay “On the Issue of Roles,” in which she levels a similar suggestion. For instance, “On the Issue of Roles” challenges men and women to discard gender definitions and find the true “self” while also maintaining that feminism is a key liberation issue for women and men who are serious about freedom and equality. Leading black feminists like Crenshaw and bell hooks echo Bambara’s assertion that if women are oppressed, if sexism endures, then freedom is compromised[1].

The point here is not critique Lemieux’s story, but to contend that young feminists need to pay more attention to Bambara’s fiction and essays, which reveal a pioneering voice that betrothed answers to the range of issues consuming contemporary feminist struggles. Indeed, Bambara’s art is in the tradition of abolitionist Maria Stewart, who deftly negotiated Christianity, nationalism, and feminism. There is no question that a deeper examination of her work is necessary, above all her revolutionary feminist approach and early transnational perspective.

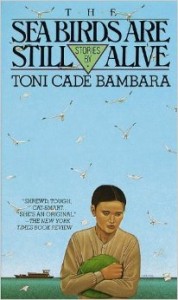

The first thing that extensive and plentiful examinations of Bambara’s work will reveal is that she was a leading voice with a transnational reach before there was a term for it. Bambara was an early transnational visionary. Hence, what we call transnational Bambara was already doing before it had a name. Indeed, transnationalism was common in Bambara’s ideological practice and artistic expressions of the 1970s and 1980s. This is easily true of her 1977 collection of fiction The Sea Birds Are Still Alive and her first novel The Salt Eaters (1980). She was deeply impacted by her 1970s trips to Vietnam and Cuba, which influenced her depiction of Asian and Algerian freedom fighters in her second collection of short stories. In two of the stories in The Sea Birds, “The Long Night” and “The Sea Birds,” Bambara focuses on revolutionary women of color entrenched in revolutionary activity or training for participation in revolutionary activity. Her global feminist perspective is unmistakable in the memorable “The Long Night,” in which she conjures a courageous young female National Liberation Front (FLN) fighter. This global feminist vision takes shape in The Salt Eaters via the spirits the Seven Sisters who represent North, Central, and South America collectively traveling together throughout the novel. Bambara lamented in several interviews how women of color missed an important moment to unite in the 1970s. The Seven Sisters seems to be her corrective of this missed moment among feminist women of color. Bambara was aware of intersectional feminist principles; she understood that one size does not fit all women—especially women of color, but she also discerned that was not a deterrent for uniting around salient issues such as sexism and racism.

The first thing that extensive and plentiful examinations of Bambara’s work will reveal is that she was a leading voice with a transnational reach before there was a term for it. Bambara was an early transnational visionary. Hence, what we call transnational Bambara was already doing before it had a name. Indeed, transnationalism was common in Bambara’s ideological practice and artistic expressions of the 1970s and 1980s. This is easily true of her 1977 collection of fiction The Sea Birds Are Still Alive and her first novel The Salt Eaters (1980). She was deeply impacted by her 1970s trips to Vietnam and Cuba, which influenced her depiction of Asian and Algerian freedom fighters in her second collection of short stories. In two of the stories in The Sea Birds, “The Long Night” and “The Sea Birds,” Bambara focuses on revolutionary women of color entrenched in revolutionary activity or training for participation in revolutionary activity. Her global feminist perspective is unmistakable in the memorable “The Long Night,” in which she conjures a courageous young female National Liberation Front (FLN) fighter. This global feminist vision takes shape in The Salt Eaters via the spirits the Seven Sisters who represent North, Central, and South America collectively traveling together throughout the novel. Bambara lamented in several interviews how women of color missed an important moment to unite in the 1970s. The Seven Sisters seems to be her corrective of this missed moment among feminist women of color. Bambara was aware of intersectional feminist principles; she understood that one size does not fit all women—especially women of color, but she also discerned that was not a deterrent for uniting around salient issues such as sexism and racism.

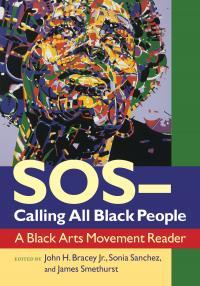

While perhaps not popular, it is true that Bambara’s transnational black feminist thrust has roots in the Black Arts Movement (BAM), which looked at blackness more globally and led to the emergence and expansion of new courses and fields of study, such as Women’s Studies, Cultural and Ethnic Studies, and Post-Colonial Studies. Like many of her BAM colleagues, Bambara’s global focus via history, literary, and cultural analysis brought to the surface issues of colonial, neo-colonial, hegemony, race, empire, gender and sexuality. Much of her work forced a reorganizing of the parameters of Black Aesthetic and black feminism to be ever-inclusive and global in scope and location. She does not allow women to be marginalized nor does she marginalize men to achieve this.

Deeper analysis of this black activist feminist scholar reveal an artist that emerged as a model of what the Black Arts encouraged: interdisciplinary, transnational, and community-oriented artistic expression. She is a model, because she imports an undeniable feminist focus, and her work is always internal, self-critical, and explores African diaspora and spirituality. Few of her peers matched her unique trans-ideological, transnational, and intersectional approach. Bambara is a unique literary figure who models how to engage day-to-day liberation in life and art. She carves out her own brand of feminism and nationalism, reminding us of figures like Septima Clark, Ella Baker, and Maria Stewart.

In Linda Janet Holmes’s wonderful biography of Toni Cade Bambara, A Joyous Revolt: Toni Cade Bambara, Writer and Activist (2014), she excerpts a May 1985 speech Bambara gave at the “Roots in Georgia” symposium at the University of Georgia. As usual, Bambara’s focus was getting the voice of the people heard over what she called “the official version of things.” Although she was speaking about John Oliver Killens, Bambara was also talking about herself when she reminded the audience, “It is not how little we know that hurts so, but that so much of what we know ain’t so.” Bambara’s life, her art, her organizing activism was consumed with delivering what she terms “usable truths to people” that differed from “the official version” of the truth.

In Linda Janet Holmes’s wonderful biography of Toni Cade Bambara, A Joyous Revolt: Toni Cade Bambara, Writer and Activist (2014), she excerpts a May 1985 speech Bambara gave at the “Roots in Georgia” symposium at the University of Georgia. As usual, Bambara’s focus was getting the voice of the people heard over what she called “the official version of things.” Although she was speaking about John Oliver Killens, Bambara was also talking about herself when she reminded the audience, “It is not how little we know that hurts so, but that so much of what we know ain’t so.” Bambara’s life, her art, her organizing activism was consumed with delivering what she terms “usable truths to people” that differed from “the official version” of the truth.

In her art, she takes the 1960s and 1970s, which many agree was an era of enormous redefinition, creativity, and social turbulence, and revises it to unite and empower various constituencies, such as neighborhoods, health systems, women, elders, children and men. The rhetoric of the time was Black Power. Her liberation impulse is empowering the disenfranchised. In life and in her fiction, her impulse models a feminist, transnational, spirit of wholeness. Thus, she bridges a world where praxis and theory can work together.

The 1960s and 1970s was a volatile moment. The tone was driven by the struggle for civil rights in the United States reaching a high point, the struggle for feminism making strides, and the resistance to U.S. imperialism, particularly in Vietnam and Cuba. Both Kennedys were murdered; so was Evers, King, and Malcolm X. The Black Panthers, whose core focus was food distribution, health education programs, and voter registration, was one of the many black organizations targeted in the late 1960s by the FBI and local law enforcement agencies. This generation pushed back. Social critiques were being launched at imperialism, capitalism, race, class, and gender. It was a scary time that many people want to forget. It also produced the more violent tone of the generation’s shift toward more revolutionary ideas. They assumed equality and demanded agency without the permission or approval of the dominant culture. As a result, the call in black communities nation-wide was for nationalism linking black politics and art together for “Black Power.” Artist of this era mostly abided by a black aesthetic that emphasized connections between ideological and functional purposes of black art.

Sometimes in contemporary academic circles, there is a tendency to ignore or dismiss the impact of this era by emphasizing contradictions or negative outcomes. But luckily, scholars like Bracey, Sanchez, Smethurst, Traylor, Ranbsy, Shockley, and others have written books that help us see the value and creative space the BAM carved for the creative developments that arose from this era. They encouraged black artists to mine black cultural elements, such as blues, jazz, call and response, and black speech, as the dominant focus in their art. These elements have proven to be central to African American literary and cultural tradition, becoming the dominant aesthetic forces in much of the contemporary works being produced. Whether the many questions raised were correct or not, what was key was that they were raised. And Bambara’s art extends this tradition more effectively than many of her contemporaries, for not only did she produce an anthology of feminist resistance and agency, but she produced literature of resistance (The Sea Birds Are Still Alive), recovery (The Salt Eaters), and renewal (Those Bones Are Not My Child) that provided necessary space for black women and men to reimagine strategies for revolution and liberation through a prism of race, gender, and class.

Sometimes in contemporary academic circles, there is a tendency to ignore or dismiss the impact of this era by emphasizing contradictions or negative outcomes. But luckily, scholars like Bracey, Sanchez, Smethurst, Traylor, Ranbsy, Shockley, and others have written books that help us see the value and creative space the BAM carved for the creative developments that arose from this era. They encouraged black artists to mine black cultural elements, such as blues, jazz, call and response, and black speech, as the dominant focus in their art. These elements have proven to be central to African American literary and cultural tradition, becoming the dominant aesthetic forces in much of the contemporary works being produced. Whether the many questions raised were correct or not, what was key was that they were raised. And Bambara’s art extends this tradition more effectively than many of her contemporaries, for not only did she produce an anthology of feminist resistance and agency, but she produced literature of resistance (The Sea Birds Are Still Alive), recovery (The Salt Eaters), and renewal (Those Bones Are Not My Child) that provided necessary space for black women and men to reimagine strategies for revolution and liberation through a prism of race, gender, and class.

The impulse of liberation in Bambara’s work represents an artistry that demands being situated in the self. In other words, the artfulness of Bambara’s activist art comes from engaging the “I,” not from separating from the text. In my own study of the liberation impulse in Bambara’s art, I engage the “I” of her distinct perspective, setting the self free. Bambara’s essays and fiction instruct us that before men can be free of racism, they must first be liberated from patriarchy and notions of what it means to be a man. And, the first step for women is similar with the added requirement that they discover their true selves absent from accepted notions of what it means to be a woman.[2] In The Salt Eaters, this is the first step Velma must take on the path to becoming whole or liberated so that she can move toward a larger representation of liberation. Bambara, through the character Minnie Ransom, reminds us that liberation comes at a cost, a small ransom, which is the price or acquiring inner liberation prior to achieving community, nation, or global liberation.

The impulse of liberation in Bambara’s work represents an artistry that demands being situated in the self. In other words, the artfulness of Bambara’s activist art comes from engaging the “I,” not from separating from the text. In my own study of the liberation impulse in Bambara’s art, I engage the “I” of her distinct perspective, setting the self free. Bambara’s essays and fiction instruct us that before men can be free of racism, they must first be liberated from patriarchy and notions of what it means to be a man. And, the first step for women is similar with the added requirement that they discover their true selves absent from accepted notions of what it means to be a woman.[2] In The Salt Eaters, this is the first step Velma must take on the path to becoming whole or liberated so that she can move toward a larger representation of liberation. Bambara, through the character Minnie Ransom, reminds us that liberation comes at a cost, a small ransom, which is the price or acquiring inner liberation prior to achieving community, nation, or global liberation.

Bambara is one of the very bright points that we want to remember. She functioned as a feminist and activist willing to challenge accepted norms to give space to marginalized and oppressed women and communities. I would agree with Linda Janet Holmes’s assessment of Bambara as a writer and activist who called for

“creating wholeness within one’s self and in the community by interconnecting sometimes competing forces emanating from still divided political and spiritual camps” (A Joyous Revolt 183).

What are the costs of not giving her legacy the treatment it deserves? First, what we lose is an important paradigm of activist scholarship wherein the activism is not just confined to the discussion realm. Bambara sustained day-to-day practices of liberation. Further, Bambara is a unique writer; she is not episodic. She teaches us the art (pun intended) of daily unglamorous liberation work. As we shift towards deeper analysis of social movement her type of work needs to be studied and modeled. As the historiography of social movements unfolds there should be a swifter shift towards Bambara-like day-to-day work for it is central to understanding practices of liberation. It is time to move her work deeper into the core of feminist and black historical memory.

****

Editors’ Note: Following is a list of of some of the literature/reading materials/pamphlets from Toni Cade Bambara’s library that Thabiti Lewis found while conducting research for his forthcoming book about her. Lewis believes this material reflects what she does in much of her fiction.

- George Breitman, Black Nationalism and Socialism

- George Breitman, How a Minority Can Change Society: The Real Potential of the Afro-American Struggle

- Evelyn Reed, The Answer to “The Naked Ape” and Other Books on Oppression

- Committee for Political Development, Change Yourself to Change the World

- The Struggle for Chicano Liberation

- LeonTrotsky on Black Nationalism and Self-Determination

- The Coup in Chile

- Liberation Support Movements, Getting Hip to Imperialism

[1] bell hooks in Killing Rage: Ending Racism (1995) broaches the issue of eliminating white supremacy and sexism. A consistent theme is coalition among those opposed to racism to join in the battle against patriarchy and those opposed to sexism and patriarchy around the issue of white supremacy.

[2] Bambara discusses the process and necessity of such discovery in her essay “On the Issue of Roles,” which implodes gender definitions for men and women and frees individuals to find self then figure out what it means for them to be a woman or a man in our society.

Dr. Thabiti Lewis is Associate professor of English at Washington State University Vancouver. He is the author of Ballers of the New School: Race and Sports in America and edited the compilation of Bambara interviews, Conversations with Toni Cade Bambara. He is currently completing a monograph, For the People: Toni Cade Bambara’s Practices of Liberation.

Dr. Thabiti Lewis is Associate professor of English at Washington State University Vancouver. He is the author of Ballers of the New School: Race and Sports in America and edited the compilation of Bambara interviews, Conversations with Toni Cade Bambara. He is currently completing a monograph, For the People: Toni Cade Bambara’s Practices of Liberation.

You may also like...

1 Comment

All Content ©2016 The Feminist Wire All Rights Reserved

Pingback: Afterword: Toni Cade Bambara's Living Legacy - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire