Bambara: What She Meant To Us/Me

By Guest Contributor on November 27, 2014By Haki R. Madhubuti

Men have got to develop some heart and some sound analysis to realize that when sisters get passionate about themselves and their direction, it does not mean they’re readying up to kick men’s ass. They’re readying up for honesty. And women have got to develop some heart and some sound analysis so they can resist the temptation of buying peace with their man with self-sacrifice and posturing. The job then regarding ‘roles’ is to submerge all breezy definitions of manhood/ womanhood (or reject them out of hand if you’re not squeamish about being called ‘neuter’) until realistic definitions emerge through a commitment to Blackhood.”

—Toni Cade Bambara, The Black Woman: An Anthology

There is brilliance and bravery written here, among the cultures of masculinity and “men run it.” There is a clear message here for the youthful years and innocent eyes of “I’ll make us a world” students. Toni Cade Bambara, in her critical, original and singular anthology The Black Woman (1970), opened the door for serious dialogue among young women and young men, like myself, who were deeply involved in street struggle, writing, teaching, on-going study, institution-building, and who were interacting with and loving Black women.

I was raised in a male-centered, sexist culture, a Black culture (Negro at that time) operating subservient to the Euro-male politics of white supremacy and white world nationalism. My early readings of W.E.B. Du Bois, Malcolm X, Frantz Fanon, Richard Wright, Carter G. Woodson, and others informed this reality. However, it was Toni Cade (before Bambara), along with Margaret Burroughs, Barbara Ann Sizemore, Gwendolyn Brooks, Ella Baker, Fannie Lou Hamer, Rosa Parks, Sonia Sanchez, Johari Amini, Carol D. Lee, and hundreds of local and national Black women in struggle and cultural work, who forced me and other men into a new consciousness, into what  sister Toni defined as “Blackhood.” Truth be told, it started much earlier for me. My mother worked in the sex trade, and the weekly struggles she endured to love, feed, house, and educate my sister and I were insurmountable and drove her to drugs, alcohol, and dangerous communities resulting in her “timely” death at the age of thirty-four. Therefore, my life circumstances forced me to—at a very young age—assess the lives of women differently than most Black boys and men. Unconsciously, around the age of fourteen, I began to study and sought out “strong” women and men to mentor me. These mentorships drove me to Black literature, and when The Black Woman was published in 1970, I immediately read and studied its content, which confirmed my own understanding of Black struggle and relationships, especially this passage by Toni Cade:

sister Toni defined as “Blackhood.” Truth be told, it started much earlier for me. My mother worked in the sex trade, and the weekly struggles she endured to love, feed, house, and educate my sister and I were insurmountable and drove her to drugs, alcohol, and dangerous communities resulting in her “timely” death at the age of thirty-four. Therefore, my life circumstances forced me to—at a very young age—assess the lives of women differently than most Black boys and men. Unconsciously, around the age of fourteen, I began to study and sought out “strong” women and men to mentor me. These mentorships drove me to Black literature, and when The Black Woman was published in 1970, I immediately read and studied its content, which confirmed my own understanding of Black struggle and relationships, especially this passage by Toni Cade:

Revolution begins with the self, in the self. The individual, the basic revolutionary unit, must be purged of poison and lies that assault the ego and threaten the heart, that hazard the next larger unit—the family or cell, that put the entire movement in peril. We make many false starts because we have been programmed to depend on white models or white interpretations of non-white models, so we don’t even ask the correct questions, much less begin to move in a correct direction. Perhaps we need to face the terrifying and overwhelming possibility that there are no models that we shall have to create from scratch. Doctrinaire Marxism is basically incompatible with Black nationalism; New Left politics is incompatible with Black nationalism; doctrinaire socialism is incompatible with Black revolution; capitalism, lord knows, is out. We need to reject too the opinions of outside “experts” who love to explain ourselves, telling the Black man that the matriarch is his enemy.

We, as artists, including Ms. Cade, were in the middle of the Black Arts Movement (BAM). Black artists of all disciplines were actively re-defining, exploring, working, acting-out, meeting, convening conferences and conventions, and teaching in and around the newly formed Black Studies departments spreading across the nation’s colleges and universities. We were also intimately involved in the cultural work of building Black independent institutions, such as schools, bookstores, magazines, newspapers, arts organizations, community co-ops, and more.

In Chicago, we had, along with Third World Press and our schools, two Black bookstores. In October 1972, a book entitled Gorilla, My Love by Toni Cade Bambara arrived on our shelves. I read it in two sittings, and began to share and teach it at Howard University, where I was on faculty at that time. I did not realize that Toni Cade had changed her name. A few of the BAM artists in a quest to redefine ourselves and our worlds also changed our names: LeRoi Jones became Amiri Baraka and I, Don L. Lee became Haki R. Madhubuti.

In Chicago, we had, along with Third World Press and our schools, two Black bookstores. In October 1972, a book entitled Gorilla, My Love by Toni Cade Bambara arrived on our shelves. I read it in two sittings, and began to share and teach it at Howard University, where I was on faculty at that time. I did not realize that Toni Cade had changed her name. A few of the BAM artists in a quest to redefine ourselves and our worlds also changed our names: LeRoi Jones became Amiri Baraka and I, Don L. Lee became Haki R. Madhubuti.

For me to rediscover Toni Cade Bambara—as a fiction writer of immense talent, insight, and moral and ethnic grounding—was a joy. I realized that I was among greatness when I read this collection of short stories, and specifically, when I read “The Lesson.” As a poet, I am unusually tuned to language: what’s said and what is not said, the local signature and sculpture of word usage, one’s choices, articulations, and combinations. As I read this passage from the first paragraph of “The Lesson,” I knew that I was home. Bambara writes:

Back in the days when everyone was old and stupid or young and foolish and me and Sugar were the only ones just right, this lady moved on our block with nappy hair and proper speech and no makeup. And quite naturally we laughed at her, laughed the way we did at the junk man who went about his business like he was some big-time president and his sorry-ass horse his secretary. And we kinda hated her too, hated the way we did the winos who cluttered up or parks and pissed on our handball walls and stank up our hallways and stairs so you couldn’t halfway play hide-and-seek without a goddamn gas mask. Miss Moore was her name. The only woman on the block with no first name. And she was black as hell, cept for her feet, which were fish-white and spooky. And she was always planning these boring-ass things for us to do, us being my cousin, mostly, who lived on the block cause we all moved North the same time and to the same apartment then spread out gradual to breathe. And our parents would yank our heads into some kinda shape and crisp up our clothes so we’d be presentable for travel with Miss Moore, who always looked like she was going to church, though she never did.

During the years of BAM (1965-1976), I traveled almost weekly across the nation and internationally. In 1974, after the publication of my book of poems, Book of Life, I was invited to read my poetry at Spelman College. After my reading that evening, I was informed that Toni Cade Bambara was teaching there. The next day, I, uninvited, walked into her class, and was greeted by her with a large, all teeth showing smile and applause from the twenty or so students. This was our first meeting but not the last.

As a poet who has been cultural, highly political, and often revolutionary in thoughts and actions, I knew upon meeting and talking to sister Bambara that I had met a kindred spirit, a sister of her word, a writer, and soon-to-be film maker, who would continue to impact the nation and world with her creations. I also knew that, just as I did, she would agree with Adrienne Rich in this statement from Poetry and Commitment:

I’m both a poet and one of the “everybodies” of my country. I live, in poetry and daily experience, with manipulated fear, ignorance, cultural confusion, and social antagonism huddling together on the fault line of an empire. In my lifetime I’ve seen the breakdown of rights and citizenship where ordinary “everybodies,” poets or not, have left politics to a political class bent on shoveling the elemental resources, the public commons of the entire world into private control. Where democracy has been left to the raiding of “acknowledged” legislators, the highest bidders. In short, to a criminal element.

Where Ms. Rich refers to “poet,” we can substitute “artist,” and her statement becomes more inclusive for all, including Ms. Bambara.

Bambara had a deep appreciation and love from her own sisterhood. I am a part of her “Blackhood” and a loving brother to the bone; however, if I’ve learned anything in struggle, I have absorbed and acknowledged the code of sisters. Her relationship with Toni Morrison was like they came from the same mother, and there were many, many others. Two women who also shared in this sisterhood were Sonia Sanchez and Dr. Eleanor W. Traylor. In talking to Professor Sanchez she quoted Toni Cade Bambara:

Once you understand what your work is and you do not try to avert your eyes from it, but attempt to invest energy in getting that work done, the universe will send you what you need. You simply have to know how to be still and receive it.

and then Sanchez added her own comments:

Indeed that’s what our dear sister Toni Cade Bambara did as she documented our bones. She. Black woman. Mother. She. World traveler. Community organizer. She practicing saint of hands threading our lives with beauty and hope. And spirit. She. Dawn mother. Born in song and prayer….singing words of life…life…life. She genius woman.

Dr. Traylor mines the field of other writers to add to her own love-note:

The pride and joy of Toni resides somewhere amid Amiri’s embodiment of her as spirit of “our bright revolutionary generation. And its fantastic desires. Its beauty. Its strength. Its struggles. Its accomplishments.” For Valerie Boyd, “she was just outrageously brilliant.” Pearl Cleage calls her “sister writer, cultural worker, mother extraordinaire, and loyal friend.” For Avery Gordon, she compels “something more powerful than skepticism.” For Cheryl A. Wall, she is “a musical obbligato, an indispensable voice, an essential component of the composite of its era.” For Toni Morrison, “she was one of our finest writers.” And for me, something wonderful pervades the universe of Toni Cade Bambara, something like “new possibilities forever in formation” to “save the planet from the psychopath.”

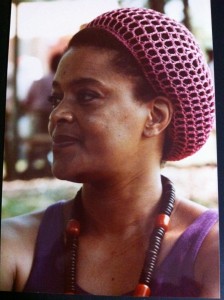

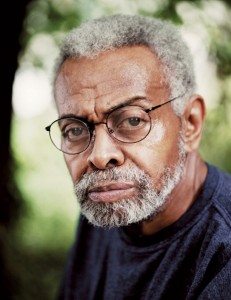

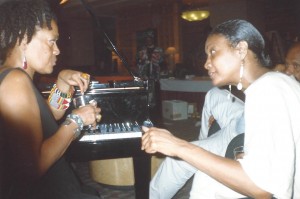

James Spadey, Eleanor Traylor, Toni Cade Bambara, Haki Madhubuti, Sonia Sanchez, 1986

Photograph ©Lamont Brown Steptoe

courtesy: H. Madhubuti

One of my last meetings with Toni Cade Bambara was in 1986 (see enclosed photo by the poet Lamont B. Steptoe) at a conference in Philadelphia organized by Dr. Traylor. For me, Bambara remains the unique questioner among us, seeking the uncommon, sub-surface entrance into the book of knowledge. The smiling sister reflecting a quiet quality directing us with her many whys, are you sure looks, let’s go at this from another angle. She was the “cultural worker” (her term) always grounding us, always leading by example toward that which was good, just, correct and right. It was her comrade in imagination and struggle, Toni Morrison, who in her book Playing in the Dark comments rather emphatically on the abuse and distortions of Black folk in western literature:

My early assumptions as a reader were that black people signified little or nothing in the imagination of white American writers. Other than as the objects of an occasional bout of jungle fever, other than to provide local color or to lend some touch of verisimilitude or to supply a needed moral gesture, humor, or bit of pathos, blacks made no appearance at all.

Toni Cade Bambara and the poets, writers, musicians, film makers, actors, playwrights, visual artist, dancers, institution builders, educators, and others of the Black Arts Movement helped to change this racist version of Black people to one that is more complete and complicated, intricate and human. Bambara states it best in the dedication of The Black Woman:

The book is dedicated to the uptown mammas who nudged me to “just set it down in print so it gets to be a habit to write letters to each other, so maybe that way we don’t keep tread milling the same old ground.”

Well, count me in and contemplate on what we are missing without our dear sister and cultural worker. Remember, most writers of all cultures do not have the shelf life of a short lead pencil. Toni Cade Bambara has proven this axiom wrong and her life’s reach in multiple genres statistically cannot be codified. She is our star among the galaxy.

Haki R. Madhubuti, poet, founder and publisher of Third World Press, is the former University Distinguished Professor and Founding Director of the MFA Program in Creative Writing at Chicago State University and former Ida B. Wells-Barnett University Professor at DePaul University. He is the author of thirty-one books, including YellowBlack: The First Twenty-One Years of a Poet’s Life, A Memoir, Liberation Narratives: New and Collected Poems 1966-2009, and most recently, Honoring Genius, Gwendolyn Brooks: The Narrative of Craft, Art, Kindness and Justice.

You may also like...

2 Comments

All Content ©2016 The Feminist Wire All Rights Reserved

Pingback: Afterword: Toni Cade Bambara's Living Legacy - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire

Pingback: The Jobs | Nonzero