My TCB Experience 1991-1995

By Guest Contributor on November 25, 2014By Amadee Braxton

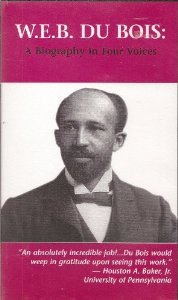

I first met Toni Cade Bambara when I was a researcher for the documentary film W.E.B. Du Bois: A Biography in Four Voices, directed by Louis Massiah and for which Toni was the coordinating writer. I was an undergraduate student then and would eventually drop out of school for a period to work full-time on the project. During the making of that film from 1991-1995, I came to view Toni as my mentor and an important role model who profoundly shaped how I see myself as an artist, cultural worker, and Black woman.

You may have noticed that Toni’s initials, T.C.B., also stand for Takin’ Care of Business, and I believe it’s no coincidence. Toni was no nonsense, sharp as a tack, and extremely quick, always ahead of the curve. She was a voracious student of the culture and a cultural critic, constantly tracking, digesting, interpreting what she saw, heard, and felt happening around her. She seemed to have seen every new international film release its opening weekend, and she tracked trends in hip-hop and every new slang or expression that would enter into the vernacular. When I met her at age 20, she was more up on hip-hop and pop culture than I was. I remember her asking me what I thought of the re-emergence of the word “nigger” among young Black people—was it a commercial gimmick or was it some legitimate expression of how young people were feeling about themselves? I wasn’t sure, I told her, maybe a little of both? I was always surprised that I felt a bit behind the times around her, because I prided myself on having my finger on the cultural pulse. But Toni was always two steps ahead. She was thorough. She also was glamorous—in the way that a confident and complex woman just is. She embodied all that I could hope to become as a woman.

I worked closely with Toni during the Du Bois process, responding to her research requests as we all tried to get right the often hidden history of Du Bois’ life and times. She would preside over the creative meetings with Louis, fellow writers Thulani Davis, Amiri Baraka, and Wesley Brown, and director of photography Arthur “AJ” Jafa. I would sit there at the ready like a grateful sponge, absorbing the wisdom spinning about, taking notes on additional research assignments the meeting would produce. These meetings could go on for hours, and were kinetic affairs covering all manner of topics, deep musings and political extrapolations tying Du Bois’ story and our history to contemporary analysis of America and our Black experience of it. If these meetings were a seven-course meal, the car rides home with Toni, Louis, and AJ, were the digestif portion of the evening, conversations where I could process all that I had been privy to.

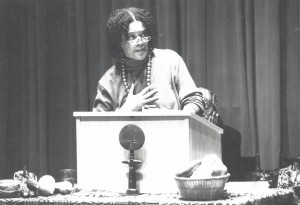

In the midst of our work on Du Bois, Toni invited me to take her documentary scriptwriting class at Scribe Video Center, the community media haven founded by Massiah that is still thriving. At the first class, Toni presented a 12-page thoroughly put together syllabus for this 4-session course that went well-beyond scriptwriting and included everything one would ever need to produce their first short documentary. At the bottom of page one of the syllabus was the heading:

WORKSHOP MEMBERS’ PHONE NUMBERS

with a lot of blank space underneath.

Toni began class by having everyone introduce themselves, identify what skills and knowledge we had, and getting agreement that we should all share our phone numbers, because we could act as crew and provide resources for each other. She set us up to be a community, whether we had planned that or not. Toni told me later on in our relationship that she was always about building community and getting people organized to be useful to each other, regardless of setting. To her, this was a practical matter. If she was standing in the grocery store and the line was moving too slowly, she would start talking to the others in line as well as the cashier to build a plan for what they ought to do about the situation.

Page three of her syllabus began:

“IDENTITY CHECKLIST

CLARIFYING YOUR STANCE AS BOTH A SPECTATOR AND A CREATOR”It went on,

“To be responsible creators, we need to recognize that we have been trained to invisibilize people in several ways that are likely to undermine our projects. Note the following unethical habits:

1) Trafficking in missing-qualifier usage: saying ‘feminist,’ for example, when we actually mean ‘European American feminists of the USA’;

2) Engaging in delusional thinking: claiming ‘objectivity,’ as though statements can be, or should be, free of self-interest, bias, or a particular perspective; claiming ‘universality,’ as though difference, diversity, cultural specificity do not exist, or that anyone is in position to know what’s ‘universal’ if everyone does not have an equal power to be heard;

3) Reducing the world to ‘Black and White,’ as though this binarism/dualism reflects reality or is an ‘innocent’ habit of speech.

AS SPECTATOR: Who is talking to you? Who does the filmmaker assume you are? Who are you?

AS CREATOR: Who are you? What is your relationship to the subjects (people/characters) of your project? Who is your intended audience?”

Toni could couch the most subversive or controversial notion into a most matter-of-fact sentence. Like when she told me that “Tragedy” was an overrated western construct and that, as Black people, she didn’t feel we had time for it. That’s why her stories focus on struggle, resilience, getting organized to do what needs to be done, or at least how to figure it out on the way to knowing the answer.

Toward the end of the Du Bois project, Toni received her cancer diagnosis. She offered to pay me $10/hr to help organize her papers, and asked me if I thought that was a fair wage. I told her yes (as it is well above the minimum wage in many places now, almost 20 years later), and I commenced to taking the suburban train out to her co-op apartment in the Germantown section of Philadelphia once a week. Actually it was two apartments combined into one, and I would sit, legs spread into a V, hunched over piles of what seemed like random scraps of paper and sorting them into file folders labeled by story title. There were lines of dialogue on a bar napkin, settings sketched out on backs of envelopes, a character name penciled on the inside of a match book. Bits of inspiration she had recorded for later. And she had reached later.

Toward the end of the Du Bois project, Toni received her cancer diagnosis. She offered to pay me $10/hr to help organize her papers, and asked me if I thought that was a fair wage. I told her yes (as it is well above the minimum wage in many places now, almost 20 years later), and I commenced to taking the suburban train out to her co-op apartment in the Germantown section of Philadelphia once a week. Actually it was two apartments combined into one, and I would sit, legs spread into a V, hunched over piles of what seemed like random scraps of paper and sorting them into file folders labeled by story title. There were lines of dialogue on a bar napkin, settings sketched out on backs of envelopes, a character name penciled on the inside of a match book. Bits of inspiration she had recorded for later. And she had reached later.

On days when her energy was good, I would sit there enthralled, losing blood circulation in my butt, sorting her papers as she would tell me stories about her life—like the time she went to Brazil for a spiritual retreat during a difficult period in her life, and was so not herself that she became completely preoccupied with an attractive young blind man who she eventually realized was not blind at all.

Or when she got the notion that it might be easier to make money being a contestant on Jeopardy than by writing—she always got every answer on Jeopardy correct, she told me—and so she went to Atlantic City when they were holding the east coast try-outs. In the first scene—Toni’s storytelling was always in scenes—she is in a huge casino ballroom with masses of white people all there to try out for the show. Most are men, and they are cramming trivia, reading books, looking at flash cards, and no one is talking to each other. She is the only woman of color in the place, and her eyes scour the room for someone to talk to, but no one will catch her eye. She spots a Chinese-American man across the way and approaches him to find out what he knows about the process. The two of them start talking and sharing ideas and everything they know. Pretty soon a crowd has gathered around them to listen in. At lunchtime, one of the crowd— middle aged white man—invites the group back to his hotel suite, which is filled with encyclopedias and almanacs. He orders room service, and they eat and share strategies, get to know each other. His wife tells Toni he’s been trying to get on the show for years, and never makes it past the first round.

Or when she got the notion that it might be easier to make money being a contestant on Jeopardy than by writing—she always got every answer on Jeopardy correct, she told me—and so she went to Atlantic City when they were holding the east coast try-outs. In the first scene—Toni’s storytelling was always in scenes—she is in a huge casino ballroom with masses of white people all there to try out for the show. Most are men, and they are cramming trivia, reading books, looking at flash cards, and no one is talking to each other. She is the only woman of color in the place, and her eyes scour the room for someone to talk to, but no one will catch her eye. She spots a Chinese-American man across the way and approaches him to find out what he knows about the process. The two of them start talking and sharing ideas and everything they know. Pretty soon a crowd has gathered around them to listen in. At lunchtime, one of the crowd— middle aged white man—invites the group back to his hotel suite, which is filled with encyclopedias and almanacs. He orders room service, and they eat and share strategies, get to know each other. His wife tells Toni he’s been trying to get on the show for years, and never makes it past the first round.

This story has many more scenes, but to cut to the chase, in the final scene, Toni is in the last round before you get to be a contestant, the one where they have you in a studio scenario to see how you handle the pressure. Under the hot lights of the fake set a question forms itself in her mind,

What the ____ am I doing here?!?

It dawns on her that in all the time she has spent going back and forth to Atlantic City for weeks, through round after round of Jeopardy try-outs, she could have written her next book. She walks off the set. End scene.

All of the stories Toni shared with me were a way of conveying her own life experiences as entertaining insights for my benefit. But the most enduring insight Toni offered me gave me a profound sense of freedom that has shaped my sense of agency in the world to this day. I was entering my junior year of college, a time when I was expected to have figured out my professional path and planned the latter part of my studies accordingly. I had developed a habit of attending all these lectures in high cultural theory, and the intellectual stimulation of that stuff made me want to stay in academia, maybe teach in higher ed. At the same time, being part of the amazing Du Bois Film project had me wanting to be a filmmaker. I also saw myself as a writer, and maybe there was something else out there I ought to be doing. (1st world problems? Maybe.) I asked Toni outright for advice on which direction I should choose. As usual her answer was very matter-of-fact:

What’s stopping you from doing all those things? Don’t feel you have to be locked-in to one thing for the rest of your life. I’ve been a teacher, a waitress; I worked on a lobster boat one summer. I’ve always been a writer, and now I’m also a filmmaker. I’ve found that you need to reinvent yourself every so often. Take what you learn from one pursuit and translate it into the next. There’s no reason you can’t do that.

I have since passed this same insight on to many confused young (and older) people who’ve come after me. I call it the TCB Art of Reinvention talk.

Thank you, Toni.

Amadee L. Braxton

Philadelphia 2014

Amadee Braxton is a facilitator, leadership coach, and trainer with Dragonfly Partners, LLC, specializing in organizational development and fundraising. For twenty years, she has worked inside non-profit organizations and as a leader in social change movements, supporting strategic thinking and developing emerging leaders. As a personal life coach, Amadee supports people to flow freely toward their goals, gain trust and confidence in their leadership, and express their vision with authenticity. Amadee also is a writer, filmmaker and Usui Reiki Master. In 2007, she was awarded the Bread & Roses Community Fund Social Justice Hero Award. She holds a Bachelor of Arts in Africana Studies from the University of Pennsylvania and a Graduate Certificate in Diversity Leadership from Temple University.

Amadee Braxton is a facilitator, leadership coach, and trainer with Dragonfly Partners, LLC, specializing in organizational development and fundraising. For twenty years, she has worked inside non-profit organizations and as a leader in social change movements, supporting strategic thinking and developing emerging leaders. As a personal life coach, Amadee supports people to flow freely toward their goals, gain trust and confidence in their leadership, and express their vision with authenticity. Amadee also is a writer, filmmaker and Usui Reiki Master. In 2007, she was awarded the Bread & Roses Community Fund Social Justice Hero Award. She holds a Bachelor of Arts in Africana Studies from the University of Pennsylvania and a Graduate Certificate in Diversity Leadership from Temple University.

You may also like...

1 Comment

All Content ©2016 The Feminist Wire All Rights Reserved

Pingback: Afterword: Toni Cade Bambara's Living Legacy - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire