Personal is Political: Toni Cade Bambara

By Guest Contributor on November 17, 2014By Paula J. Giddings

Toni Cade Bambara was a prophet. She even lived like one: wholly unconventional, residing in urban netherlands, full of laughter and a brightness of eye that let you know she was seeing something you were not.

For me, particularly prescient was The Black Woman, her edited anthology (1970) that was published the year after I graduated from Howard University. I was eager to be apart of a movement that, as Toni wrote in the preface, had us turning to each other for answers.

At the time, there were roiling debates about black women in the wake of the mainstream women’s movement, the Moynihan Report and the masculinism of Black Power. These shots across the bow of black womanhood only seemed to stir our imagination and political will. Nineteen-seventy also saw the publication of The Bluest Eye (Morrison), The Third Life of Grange Copeland (Walker), and Unbought and Unbossed (Chisholm), among others.

But where were we, and who were we, in the overall scheme of things? Where were we heading?

In Bambara’s preface, she set out the path that would lead us “to find out what liberation for ourselves means, what work it entails, what benefits it will yield.” She listed twelve items that she hoped the book would kick start by any means necessary: “poems, stories, essays, formal, informal, reminiscent.” These included a comparative study and working alliance with all “non-white women of the world;” viable alternatives to the public school system; consumer education and cooperative economics; setting the record straight on the “matriarch” and the “evil Black bitch;” getting into the “whole area of sensuality, sex;” providing a forum of opinion from the “YWCA to the Black Women Enraged;” and of course, “delve into history and pay tribute to all our warriors from the ancient times to the slave trade to Harriet Tubman to Fannie Lou Hamer to the woman of this morning…”

The relevance of the to-do list, nearly a half-century later is remarkable; the sensibility definitely our own; and the attitude shaped the attitude of succeeding generations. As Beverly Guy-Sheftall and bell hooks have pointed out, The Black Woman showed us a still unfamiliar and highly contested terrain: a transformative vision of the world not from without, but from within black feminism. At the dawn of theory, this was what it looked like, felt like, read like—it was unique—and glorious.

We not only welcomed the vision then but wore it tightly, like a life jacket, as the number of naysayers who mocked the idea that we were even worthy as stand-alone subjects proliferated.

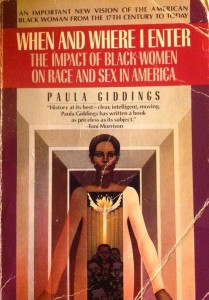

One of them, an influential magazine publisher whom I admired, advised that I would become a laughing stock if I tried to publish my first book, When and Where I Enter (1984). Remembering that moment makes me think how many of us were discouraged by such words. Thankfully, the already sanctified shores of The Black Woman were there—and in sight.

One of them, an influential magazine publisher whom I admired, advised that I would become a laughing stock if I tried to publish my first book, When and Where I Enter (1984). Remembering that moment makes me think how many of us were discouraged by such words. Thankfully, the already sanctified shores of The Black Woman were there—and in sight.

Paula J. Giddings is the Elizabeth A. Woodson 1922 Professor of Afro-American Studies at Smith College, where she is the editor of the journal, Meridians: feminism, race, transnationalism. She is the author of When and Where I Enter: The Impact on Black Women on Race and Sex in America; In Search of Sisterhood, Delta Sigma Theta and the Challenge of the Black Sorority Movement; Burning All Illusions; editor of an anthology of articles on race published by the Nation magazine from 1867 to 2000; and Ida, A Sword Among Lions: Ida B. Wells and the Campaign Against Lynching, which received the Los Angeles Times Book Prize in Biography and Letitia Woods Brown Book Award from the Association of Black Women Historians, among other awards.

Paula J. Giddings is the Elizabeth A. Woodson 1922 Professor of Afro-American Studies at Smith College, where she is the editor of the journal, Meridians: feminism, race, transnationalism. She is the author of When and Where I Enter: The Impact on Black Women on Race and Sex in America; In Search of Sisterhood, Delta Sigma Theta and the Challenge of the Black Sorority Movement; Burning All Illusions; editor of an anthology of articles on race published by the Nation magazine from 1867 to 2000; and Ida, A Sword Among Lions: Ida B. Wells and the Campaign Against Lynching, which received the Los Angeles Times Book Prize in Biography and Letitia Woods Brown Book Award from the Association of Black Women Historians, among other awards.

You may also like...

1 Comment

All Content ©2016 The Feminist Wire All Rights Reserved

Pingback: Afterword: Toni Cade Bambara's Living Legacy - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire