A Review of Koblitz’s “Sex and Herbs and Birth Control”

By Tiffany Lamoreaux

Addressing an Iowa audience in August 2014, Republican Rand Paul claimed that the GOP was not interested in banning birth control. Instead, Paul claimed, the “war on women” is simply an exaggerated and/or made-up narrative perpetuated by Democrats. Never mind that Paul had, as recently as 2013, co-sponsored personhood legislation that would effectively outlaw several types of birth control. Was Paul lying in order to appear more moderate, hoping that nobody would remember his past actions against birth control? Perhaps not. Paul might be completely sincere in his belief that he and other Republicans are not attempting to ban “birth control” because of the way that he defines pregnancy and what counts as birth control versus abortifacients. How we define pregnancy and life – and what types of behaviors or actions can be taken to prevent or end said life/not life – remains one of the most important feminist struggles of our time.

Luckily, the recently released book Sex and Herbs and Birth Control, written by Ann Hibner Koblitz, is available for anyone interested in gaining a better understanding of the rich and complex history surrounding women’s reproductive agency and choices. Although we like to imagine that people in the past were more conservative in their views on reproduction than our so-called progressive and “liberal” views, Koblitz illustrates historical (and religious) precedents for abortion –or at the very least, a much more relaxed acceptance of “restoring menses” for women before mid-20th century. This book, which attests to the ingenuity of women in controlling their fertility, represents a brilliant interdisciplinary approach to women’s history and the history of reproductive regulation in the U.S. and Western Europe. The author offers a nuanced critique of the ways in which women have been and continue to be silenced by victimization narratives from anti-abortion, pro-choice activists, medical practitioners, and politicians alike in the fight to control women’s reproductive behaviors. Koblitz moves the debate beyond the discursive woman / dead fetus binary and shows how women historically had many effective means of reproductive control, at least until those knowledge systems and methods were lost, hidden, or legislated away due to shifting politics and cultural beliefs.

Luckily, the recently released book Sex and Herbs and Birth Control, written by Ann Hibner Koblitz, is available for anyone interested in gaining a better understanding of the rich and complex history surrounding women’s reproductive agency and choices. Although we like to imagine that people in the past were more conservative in their views on reproduction than our so-called progressive and “liberal” views, Koblitz illustrates historical (and religious) precedents for abortion –or at the very least, a much more relaxed acceptance of “restoring menses” for women before mid-20th century. This book, which attests to the ingenuity of women in controlling their fertility, represents a brilliant interdisciplinary approach to women’s history and the history of reproductive regulation in the U.S. and Western Europe. The author offers a nuanced critique of the ways in which women have been and continue to be silenced by victimization narratives from anti-abortion, pro-choice activists, medical practitioners, and politicians alike in the fight to control women’s reproductive behaviors. Koblitz moves the debate beyond the discursive woman / dead fetus binary and shows how women historically had many effective means of reproductive control, at least until those knowledge systems and methods were lost, hidden, or legislated away due to shifting politics and cultural beliefs.

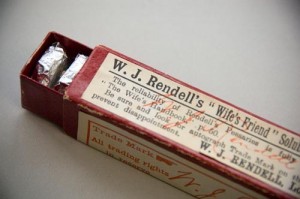

In general, the author lays out how cultures (historically and contemporarily) vary in their beliefs about the precise definition of pregnancy. The idea that “life” and pregnancy begin at the moment of conception is a rather recent belief, and before the mid-20th century women might not have considered themselves pregnant until sometime in the second trimester. According to Koblitz, the variation in pregnancy definitions allowed ample moral and ethical ‘wiggle’ room for women to take matters into their own hands, so to speak. Regardless of the legality of what was deemed abortion at the time, many women did have access to a number of resources to restore menses (i.e., to abort a fetus) or otherwise control their fertility (with pre-conception methods) available to them. Such resources included (now lost) herbal knowledge passed down from generations of women before them, to midwives with pessaries and uterine sounds, to (less effective) patent medications and douches. This book examines each of these methods and portrays women as active agents controlling their fertility rather than helpless victims of back alley abortionists or ignorant dupes to patent medicine hucksters.

The idea that there is variation in the definition of pregnancy between cultures and historical periods stands out as an extremely valuable fact considering that women’s abilities to control their fertility are consistently part of a larger national public debate, espeically in the U.S. In fact, the recent Supreme Court ruling on Burwell v. Hobby Lobby (2014) effectively allowed for “closely-held” corporations to claim exemption from the birth control mandate of the ACA due to so-called religious beliefs. The idea that a Christian-run corporation can “believe” that “morning after” birth control pills and intrauterine devices (IUDs) work as abortifacients reveals just some of the variations in beliefs about what counts as the beginning of pregnancy and what this means for pre- and post-conception regulation. The current belief being adopted by the political Right and Evangelical Christians is that pregnancy begins at the exact moment a sperm cell has joined with an egg cell; therefore, many believe that anything that interferes with any process after that moment is ostensibly an abortifacient. Koblitz’s book provides a detailed history of how these ideas have developed and shifted over the years and who has constantly lost-out. (Here’s a hint, it’s women!)

Some of the most fascinating passages in this book include the author’s critiques of medical science, specifically the rise of forensic pathology as a field and its disastrous consequences for women’s reproductive choices. For example, Koblitz writes that “late 19th-and early 20th-century forensic pathologists and gynecologists often claimed far more certainty about their ability to detect criminal interference with pregnancy than was warranted” and used this “knowledge” to legitimate their field and carve out a space for themselves as “experts” in legal proceedings (page 156). Koblitz also takes issue with the field of demography, arguing that demographers have erased women’s roles as agents of demographic change (page 202). Koblitz’s most thought-provoking point, in my opinion, is her critique of Margaret Sanger. Coming in stark contrast to many feminists who view Sanger as a champion for women’s reproductive choice, Koblitz speculates that “it is possible that the choices she made and tactics she employed contributed to the deteriorating conditions under which abortions (other than therapeutic ones) were performed in those years” (page 183).

The author is a historian but her evidence includes both past and present sources. Her writing style is straightforward and thoughtful, making this work read more like a conversation with a well-informed friend and less like the rigorous academic study that it represents. This book would make a great text for college-level women’s studies, medical science, history of medicine, philosophy of science, and/or science and technology studies courses. Sex and Herbs and Birth Control is also relevant for practitioners operating somewhat outside the clinicalized mainstream reproductive healthcare sector, such as midwives and doulas, due to the author’s identification and appreciation of their expertise, praxis, and politics across the ages. The most important takeaway lesson from this book is that things are not always better with time and keeping women in control of their reproductive choices is going to require constant vigilance and work.

Details: Ann Hibner Koblitz, 2014. Sex and Herbs and Birth Control: Women and Fertility Regulation Through the Ages. Published by the Kovalevskaia Fund. ISBN: 978-0-9896655-0-6.

___________________________________

Tiffany Lamoreaux, Ph.D., is an adjunct professor of Women and Gender Studies. Her research interests include sexuality; race and class; race and gender in science fiction; gender, science, and technology; and the history of women’s work.

Tiffany Lamoreaux, Ph.D., is an adjunct professor of Women and Gender Studies. Her research interests include sexuality; race and class; race and gender in science fiction; gender, science, and technology; and the history of women’s work.

Pingback: Sex & Herbs & Birth Control | ahkoblitz

Pingback: Book Review Highlights Key Points Concerning Women’s Reproductive Rights | thefeministblogproject