COLLEGE FEMINISMS: Bringing “All” to the Tent of Communal Healing

By Ahmad Greene-Hayes

Inspired by the story of a Black enslaved woman, Margaret Garner, Toni Morrison’s 1987 novel Beloved explores the narrative of Sethe, who killed her daughter Beloved to protect her from the racialized and sexualized violence of slavery. After leaving her former plantation—Sweet Home—and rejected, Beloved’s ghost returns from the grave to haunt Sethe and those who live with her in 124. Her vengeance grows increasingly vehement once she reincarnates as a full-grown woman.

Once the town women catch wind of the devil-like happenings within 124, they galvanize. Led by Ella—who resembles Black feminist warrior Ella Baker—they head towards the house with prayer and song. Invoking the spirit of Baby Suggs, who had so diligently ministered to the women in this community for years, they are able to break the yoke of bondage from Sethe. Beloved’s grip—so strong a force that once held Sethe’s mind, body, and faculties—is relinquished as the chains that confined her to 124 are broken. Beloved was exorcised.

Morrison uses the novel, Beloved, to address how Blacks must exorcise themselves of the hurt, pain, and brokenness of slavery’s ghost. The novel also provides a useful lens for viewing the Black church and its role in this transgenerational healing process.

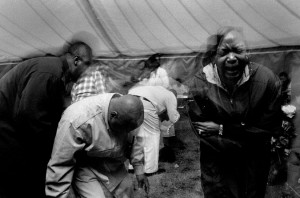

This summer, a plethora of Black churches joined together, like the women in Beloved, to exorcise themselves of spiritual ills. These gatherings occur under tents and are called “tent revivals.” They take place outside in the heat of summer, usually in the evenings as the cool summer breeze blows, the sun sets, and the sweet aroma of flowers grace the nostrils of the youngest child to the eldest congregant. Sermons are preached, people shout and dance, yell and scream, and their respective communities bear witness to the performative and spiritual practices typically confined to the four walls of their churches. The avowedly saved, sanctified, and Holy Ghost-filled saints gather under these erected tents to invoke the presence of God and to call down “revival.”

Though tent revivals are spaces for communal healing within many Black communities, only certain individuals are embraced under the tent. When some individuals enter, the significances of their lived experiences are relegated to the shadows. Two particular identity groups come to mind—Black queer folk and Black women— though there are so many others. When Black LGBT-identifying individuals attend church services and tent revivals, they are pathologized and deemed ungodly. When Black women, who make up a large portion of the Black church populace, enter the tent, they are called Sister, Evangelist or Pastor, and then told to submit and serve the men.

In many regards, Morrison’s Beloved shows us how some Black women counteract these norms by subversively disrupting notions that they remain silenced. In so doing, they travail for their own personal spiritual exorcisms in ways fully separate from men. However, twenty-seven years after Beloved’s publishing, the tent of Black churches—consumed with the adulation of the Black male patriarch—is still stuck in the days of female subjugation and heteropatriarchy, and are ultimately resistant to faith feminisms and queer inclusivity.

Tent revivals have deep histories. People in the U.S. South, historically former enslaved Blacks and African Americans living during Jim Crow, would gather hoping to receive manna from heaven to give them strength for the journey of resistance ahead [1]. When enslaved women were sexually abused on the plantation, as depicted in Morrison’s Beloved, these assemblies were spaces for them to heal together. When enslaved men were castrated or brutally beaten, these meetings afforded them the chance to cry, to breathe, and to gain strength from on high. When enslaved children were violated, these get-togethers gave them space to find restoration from their trauma. For my ancestors, the “tent” was metaphoric, if not solely representative of how God can hide the oppressed under an Almighty shadow.

The happenings in Morrison’s Beloved did not occur under a physical tent, but the events underscored irradiate communal healing. That is, a battered group of individuals—more specifically, Black women—joined together in the spirit of love, reconciliation, and as Morrison demonstrates, exorcism. It also accentuates how Black women have fought tirelessly to keep Black churches open; in fact, they have labored so church buildings, tent poles, and gathering grounds could remain accessible. Though the Black church has had its share of issues, it has been a space where the love and forgiveness of God can be exemplified in the lives of its believers.

How, then, do we reconcile the powerful history of Black churches and tents with the ways they also marginalize and disregard voices? Jesus said in Matthew 11:28, “Come unto me, all ye that labour and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest.” Yet, so many come and are turned away by the pervasive bigotry—directed at Black queer folk and Black women—interwoven with the hateful and harmful theologies spewed from pulpits and fostered under summer revival tents.

***

Wholeness refers to at least three interrelated aspects of the Black struggle. First, it implies that an individual is whole, that is, spiritually, emotionally, psychically, and physically healed from the wounds of his/her oppression. Second, wholeness suggests that the Black community is not divided against itself in terms of harboring sexism, classism, colorism, or heterosexism. In other words, the community is free from “horizontal violence.” Finally, wholeness means that the community itself is free, liberated from oppression, so that each member of the community can fulfill his/her singular potential as a child of God.

—Dr. Kelly Brown Douglas (1999: 128)

***

I was raised in the Black church. I’ve heard church folk use the f-word and purport the myth of female inferiority all in one breath. These scenarios are all too common. They happen at almost every church gathering. For example, one evening after my church’s pastor taught a bible study class about sexual perversion, the openly gay, male mass choir secretary approached him saying, “I guess I’m going to bust hell wide open, because my Tim has been just too good to me.” And in reply, the Pastor told him, “You sure will,” without hesitancy. Many Black queer people and many Black women feel oppressed by the very same churches that they pay their tithes to or support at every waking moment. So many Black churches need to be exorcised from the social sins of homophobia, transphobia, misogyny, sexism, and heterosexism. Black queer folk and Black women who love Jesus should not have to sacrifice their humanity just to feel safe and protected while enjoying the Black cultural and spiritual practices inherent to Black churches and their summer revival tents.

When will the Black church-at-large speak and become inclusive to the unique lived experiences of queer Black women and men? When will the Black church stop making excuses for child molesters and down-low brothers in the pulpit like Eddie S. Long?

The Independent Lens documentary, The New Black, and PBS’ forthcoming segment on Gospel artist Tonex, are echoing these seemingly age-old questions and concerns. In 2014, we have witnessed so many racialized and gendered attacks on queer people of color—for instance, the attack of two Black trans women on a MARTA train in Atlanta, Georgia, the murder of Black lesbians Britney Cosby and Crystal Jackson from Houston, Texas, and the murders of 27-year-old Ahmed Said and 23-year-old Dwone Anderson-Young from Seattle, Washington this summer. Though these three cases may not be tied directly to the Black church, they are related. It is common in Black churches, among many other religious organizations, for queer violence to be preached in the name of a man-identified homophobic god. Harmful and hurtful theologies encourage physical violence, murder, and death—words, too, can kill.

Not only are these spaces complicit in anti-queer rhetoric, but they also perpetuate misogynoir, as seen in Pastor Jamal H. Bryant’s recent “these hoes ain’t loyal” comment in a sermon at his Baltimore church. Dr. Brittney Cooper penned, “Jesus Wasn’t A Slut-Shamer,” to accentuate the quandaries of attending Black churches while identifying as a faith feminist. Like Cooper, “I love Jesus, and I remain a person of faith, because I know, to put it in the parlance of the Black Churches of my youth, how good God has been to me.” Importantly as Cooper also writes, “what I am not is a person who will willingly check [their] brain, political convictions, or academic training at the door in order to enter the house of God or to participate in a community of faith.”

The God I serve is a god of love. In fact, they are love. God is not a man. God does not have a race. God is a spirit. A loving spirit. A spirit that reaches down to the deepest depths of the human spirit and loves without respect of persons. As the late Maya Angelou once said during Oprah Winfrey’s Super Soul Sundays, “God is All.”

Tent revivals and black churches will not precipitate true communal healing unless they are driven and informed by “All.” Communal healing comes from a love ethos predicated on anti-colonial, anti-misogynistic, feminist, and queer inclusive themes and ideologies. Unless the Black church addresses its involvement in preserving and perpetuating neoslavery narratives, it will remain dead. Black communities are in need of communal healing, as Black people continue facing the undying and persistent legacies of colonialism, enslavement, and Jim Crow. Sadly, the Black church and its tent—stuck in the bygone days of efficacy—may no longer provide transformation. Revivals need not be solely traditional, rather, they must embody a revolutionary theology, a Womanist theology, an all-inclusive theology. For truly, revival without “All” is not revival.

*****

[1] It should be noted, however, that white ministers from the slaveholding class proselytized blacks to a Christian God, and that the enslaved then adopted the spiritual and religious beliefs of their enslavers (Harrell, 1975). Blacks, then, formed a symbiosis of African culture and white religious practices. Creatively, they found enigmatic ways to incorporate African theological principles, healing tales and rituals, song, and dance, all while subsuming to the commands of their “holy-rolling” enslavers (Spillers, “Moving on Down the Line,” 1988). Though white influence cannot be denied, the gathering of Blacks on the plantation to commune with God and the ancestors was uniquely Black, that is, solely characteristic of peoples stolen from Africa and brought to the Americas.

***********************************************************

Ahmad Greene-Hayes is a student at Williams College, a Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellow, a Jackie Robinson Scholar, a History major, and an Africana Studies concentrator. He is a male-Womanist and a radical voice in a generation of upcoming scholars and activists. Ahmad is co-founder of Kaleidoscopes: Diaspora Re-imagined, a student-run academic journal that offers a space for scholars and social activists to interrogate issues pertinent to the African diaspora, while concomitantly deconstructing dominant historical discourses involving people of African descent. Follow him on Twitter @_BrothaG.

Ahmad Greene-Hayes is a student at Williams College, a Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellow, a Jackie Robinson Scholar, a History major, and an Africana Studies concentrator. He is a male-Womanist and a radical voice in a generation of upcoming scholars and activists. Ahmad is co-founder of Kaleidoscopes: Diaspora Re-imagined, a student-run academic journal that offers a space for scholars and social activists to interrogate issues pertinent to the African diaspora, while concomitantly deconstructing dominant historical discourses involving people of African descent. Follow him on Twitter @_BrothaG.

0 comments